Publication

Would you fight for your country?

Summary

The article presents results of the “Global Barometer of Hope and Despair”; survey, conducted in 2023 by the Gallup International Association in 45 countries, including Armenia. Preliminary analysis of the results related to the question: “Would you fight for your country?” are carried out. Some culturomics aspects of the question are analyzed via Google Books N-gram Viewer tool.

ԿԿՌՎԵ՞Ք, ԱՐԴՅՈՔ, ՁԵՐ ԵՐԿՐԻ ՀԱՄԱՐ

Մարջանյան Ա. Հ.

Սեղմագիր

Հոդվածում ներկայացված են «Հույսի և հուսահատության գլոբալ բարոմետր» հետազոտության արդյունքները, որն անցկացրել է Gallup International Association-ը 2023 թ. 45 երկրներում, այդ թվում՝ Հայաստանում։ Կատարվում է «Կկռվե՞ք, արդյոք, ձեր երկրի համար» հարցի պատասխանների նախնական վերլուծությունը։ Google Books N-gram Viewer գործիքի միջոցով վերլուծվում են հարցի որոշ մշակութաբանական ասպեկտներ։

БУДЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ СРАЖАТЬСЯ ЗА СВОЮ СТРАНУ?

Марджанян А. А.

Аннотация

В статье представлены результаты исследования «Глобальный барометр надежды и отчаяния», проведенного в 2023 году Международной ассоциацией Gallup в 45 странах, в том числе в Армении. Проведен предварительный анализ результатов по вопросу «Будете ли вы сражаться за свою страну?». Некоторые культуромические аспекты вопроса анализируются с помощью инструмента Google Books N-gram Viewer.

INTRODUCTION

“And I’m begging you. / Be a little mathematician, / But provided this comforter.

Do not add a lie to truth, / But divide the lie by truth.

Do not add sadness to grief / But divide them, sadness by grief”:

Paruyr Sevak, 1957(3)

There are many surveys in the world of what is commonly called “public opinion”. They are often meaningless, sometimes important and meaningful. The purpose of our article is to acquaint the reader with the results of one such survey that was conducted as part of the “Global Barometer of Hope and Despair”(4) project by Gallup International Association (GIA) in 45 countries of the world at the end of 2023 [1].

In Armenia the survey was conducted by MPG LLC by means of a computer and telephone survey among 1100 citizens aged over 18. In Azerbaijan it was carried out by SIAR Research & Consulting Group, through a simple telephone survey among 500 citizens over 18. In the Russian Federation, unlike previous years, the survey was conducted by Be Media Consultant among 1200 citizens over 18, using the Internet survey method(5). In total, from October to December 2023, 46138 people were interviewed in 45 countries of the world, according to an average country representative sample of about 1000 men and women. The survey error ranged from +3 to 5% with a 95% confidence [1].

Among other things, respondents were asked to answer the question: “If there was a war involving (YOUR COUNTRY), would you fight for your country”?

Since this question had raised to us not only, and not so much, by the Gallup International, but rather by life and destiny itself, and not only at the end of 2023, but also over the course of several decades, it is interesting to analyze the data obtained and compare them with our perceptions.

The form of words (a culturomical excursus)

“What kind of house is this”, he said / “Where I have come to roam?”

“It’s not a house”, says Judas Priest / “It’s not a house, it’s a home”

Bob Dylan, 1967(6).

We do not know for certain how exactly this question was formulated in specific countries, for example in Armenian, Azerbaijani or Russian languages. At the time of writing our article (April 2024), the results were not published in Armenian, as well as in other languages. On the official website of Gallup International there is only a short report of the 2023 survey, of course, in English [1]. And hundreds of publications on this topic, issued in dozens of languages around the world by various resources in recent days and weeks, have referred only to this English-language report. Moreover, the results are presented without any analysis.

However, in real life, this question was asked in 43 different languages and in 45 countries of the world, thereby raising at least 45 different complexes of “language/word/cultural-historical linguistic interpretation” interactions. After all, it’s one thing, let’s say, to ask in Russian, “Would you fight for your country?” And it’s another thing to pose the question “Would you fight for your homeland”, or “Motherland” with a capital letter, or even for “Fatherland” (Patria). One thing is to preface the question with some kind of preamble clarifying the situation, for example, to say in advance “If your homeland is attacked, would you fight for it?” And it’s another thing to ask: “If your country attacks an enemy, will you still fight for it”, etc. And here, once again, we find ourselves on the thin ice with the problem of translation, connotation and interpretation of words in various linguistic environments.

The question we are interested in was formulated in English (the original survey template) as follows: “If there were a war that involved (YOUR COUNTRY), would you be willing to fight for your country?”, with answer options “Yes”, “No” and “Don’t know” or “No response” (DK/NR) [1]. The national teams could only insert the name of the country, where the survey was conducted, instead of brackets and strictly follow the lexical logic and form of the template when translating. We will assume that in Russian and Armenian the question was asked correctly”(7).

The first thing that catches one’s eye here is the desire of the survey organizers to use emotionally neutral language. Why was the rather cumbersome preamble “If there were a war that involved your country” needed in the English template? The compilers clearly avoid specifying which war they are talking about. After all, it is one thing if your country has been subjected to (an unprovoked) military aggression, and you have the moral justification and legal right to wage a defensive war, driven by patterns of patriotic mythology or by invoking Article 51 of the UN Charter(8). Another matter is if it is your country that started a war and is, in fact, an aggressor. But the GIA survey bypasses all these subtleties and proceeds, as it were, from a fait accompli, i. e. – your country has already been involved in the war. And the question now is whether you will fight for it or not.

The second thing is that, that organizers deliberately used the neutral concept of “YOUR COUNTRY”, avoiding the use of such emotionally charged words as “homeland” or “fatherland”. Which brings us to the interesting question of the different connotations and frequency of the use (usage) of such words as “country”, “homeland”, “fatherland”, “страна”, “родина”, “отчизна”, “երկիր”, “էրկիր”, “հայրենիք”, “patria”, “vaterland”, etc., in different linguistic and cultural environments and in different historical times.

Fortunately, after the “Great December Revolution of 2010” and the creation of the “Google N-grams” tool [3], it turned out to be possible to investigate qualitatively and, most importantly, quantitatively, such issues with unprecedented accuracy. Although only for some, very few, language environments(9). The entire range of these issues is discussed in more detail in [3]; so, we refer the interested reader to it and the literature cited there.

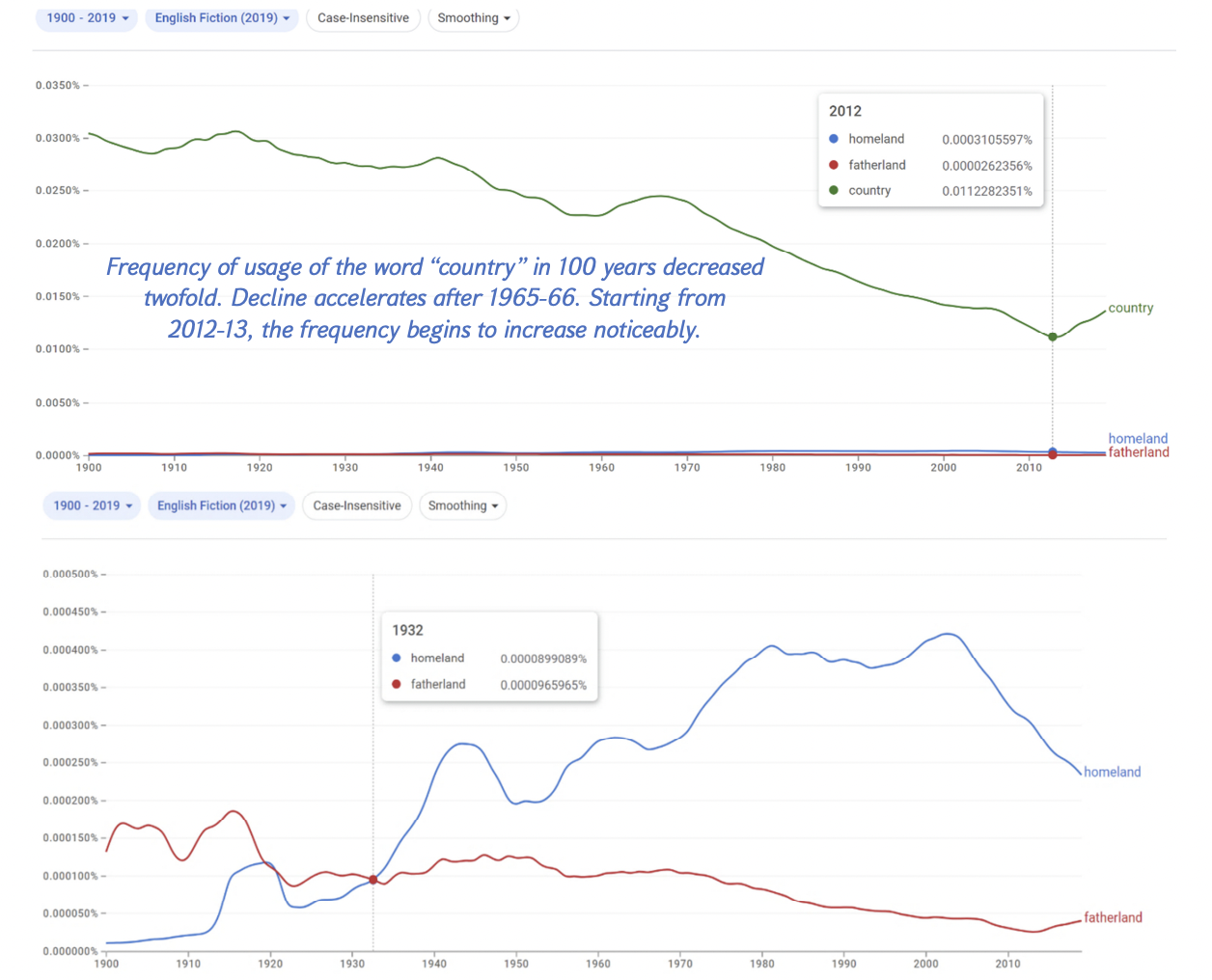

Figure 1. Frequency (%) of separate words (1-grams) “country”, “homeland” and “fatherland” in same scale, (above). Separately for only “homeland” and “fatherland” (below). The Corpus of English Fiction, 1900-2019.

Source: Google Books N-gram Viewer.

Here, we will limit ourselves by using the N-gram tool to build curves for the frequency of usage of three different words (1-gram): “country”, “homeland” and “fatherland”(10), in the so-called Corpus of the English literary language(11), which includes books and articles published since 1900 to 2019, Fig. 1 (above). This Corpus consists of breathtaking 361 billion(12) instances of the usage of individual words (1-grams) or their various combinations (N-grams, where N can be up to 10).

As we can see, the frequency of usage of the word “country” in this staggering corpus far exceeds the frequency of the words “homeland” and “fatherland”, almost throughout the entire period in question. In this sense, it can be considered indeed “commonly used” in the widest context, and therefore it can be considered as “neutral”. This superiority is so great, that reproduction of the curves of these three words on one chart with same scale, suppresses the curves of “homeland” and “fatherland”, making them practically indistinguishable (see Fig. 1, above). Nevertheless, an important cultural, historical and linguistic feature of English literary language is already noticeable here: a gradual decrease of usage of the word “country” in English throughout the entire 20th century.

Moreover, the rate of decline has been increasing since the mid-60s of the last century (figuratively speaking, since “May 1968” and the “sexual revolution” [4]). After 2012-13, the frequency of usage of the word “country” began to increase, first time in more than 100 years (see Fig. 1, above). In our opinion, this is a bright, “linguistic” illustration of the victorious march of the “globalization” era, which began in the 70s of the last century and lasted for more than three decades. Until the crisis of 2009 and the start of the “American-Chinese” global confrontation, comprehended by the Anglo-Saxon world in the beginning of the 2010s.

To revile peculiarities of the “homeland” and “fatherland” usage, in Fig. 1, bellow, we present the curves only for these two words. The picture is very revealing. As we can see, before 1914 and the World War I (“The Great War” in the English-speaking cultural environment), the frequency of usage of the word “fatherland” noticeably exceeds the frequency of the original “Anglo-Saxon” word “homeland”. After the “Great War” and the defeat of Germany, there was a noticeable decrease in the frequency of the “fatherland” usage. And vice versa, there is a noticeable increase in the frequency of usage of the word “homeland”. It reaches its first peak in the second half of the twenties of the 20th century. The two curves intersect in 1932, on the eve of the Nazi Party coming to power in Germany. The frequency of the word “homeland” reached its second pea

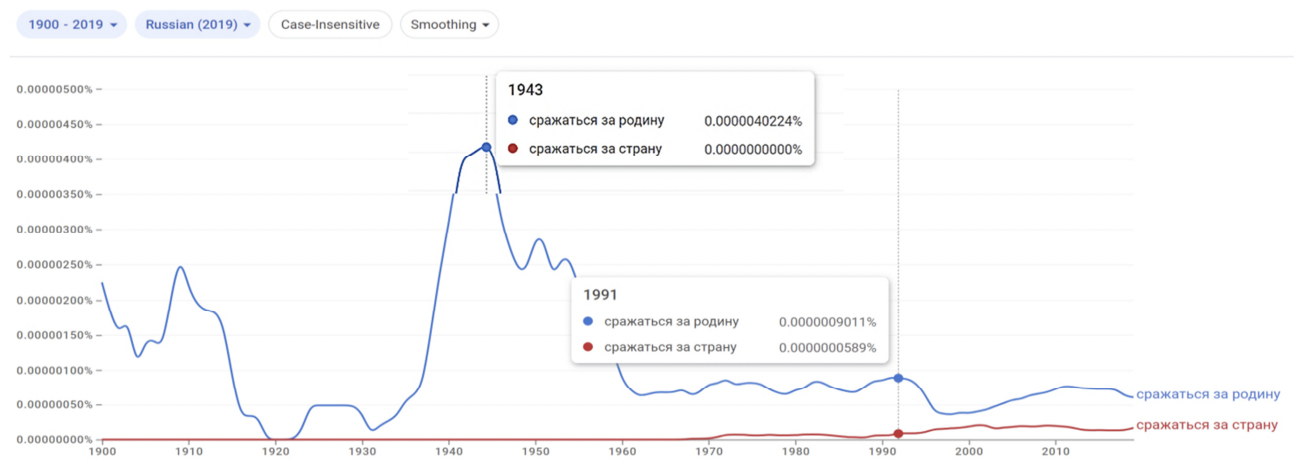

Figure 2. Frequency of the usage phrases (3-grams) “to fight for homeland” and “to fight for the country”. The Corpus of the Russian language, 1900–2019.

Source: Google Books N-gram Viewer.

at the height of the World War II and then remained noticeably higher than the frequency of the “fatherland”, strongly reminiscent of the “German”, if not “Nazi” origin(13).

In order to illustrate the possibilities of the “N-grams” tool and to reveal the linguistic and cultural-historical features of the Russian language, on Fig. 2 we present two frequency curves for three-word combination (3-grams) “to fight for the homeland” (“сражаться за родину”) and “to fight for the country” (“сражаться за страну”) in the Corpus of the Russian language, from 1900 to 2019.

Without going into the details, let us highlight only two things related to the subject of our article. First, the frequency curve of the phrase “fight for the homeland” has two clear peaks for the periods of WWI and WWII. Secondly, the usage of phrase “fighting for the country” has an almost zero frequency until the beginning of the “Détente”(14) in the 1970s. A noticeable increase of the frequency of “fighting for the country” begins only after the collapse of the USSR in 1991, see Fig. 2.

Needless to say, that the corpus Armenian language, despite the significant achievements of the 60s and 80s, has not been created until today. Otherwise, it would be interesting to compare the frequency of the usage of “Death or Freedom”, “Death or Homeland”, possibly even “Homeland or Freedom” phrases, in the Corpus of Armenian language, and let say over1900 to 2024 time period(15).

Summing up this “culturomical” excursus, we want to stress:

The importance of language (and translation) in international public opinion surveys;

The volume and consequences of the measures taken to preserve the “neutrality” of the question considered here of the GIA 2023 survey;

Immanent, indestructibility presence of the linguistic and cultural-historical “background”, hidden behind the results of a public opinion surveys, like GIA “EoY”.

By prefacing the question with a “cunning” preamble and using the expression (YOUR COUNTRY), GIA really attached certain “neutrality” to the question posed, but in no way neutralized the linguistic and cultural-historical features inherent in different linguistic environments. Given the tendency of the human brain to simplify any task, including socio-linguistic ones, undoubtedly the GIA question was perceived on an emotional and subconscious level, as a simple, straightforward and clear question. “Will you fight for your country”? Perhaps even as “Will you fight for your Homeland”.

2. results. Preliminary analysis

“And do not brag about the question. / Just be proud of the solution!”

Paruyr Sevak, 1957.

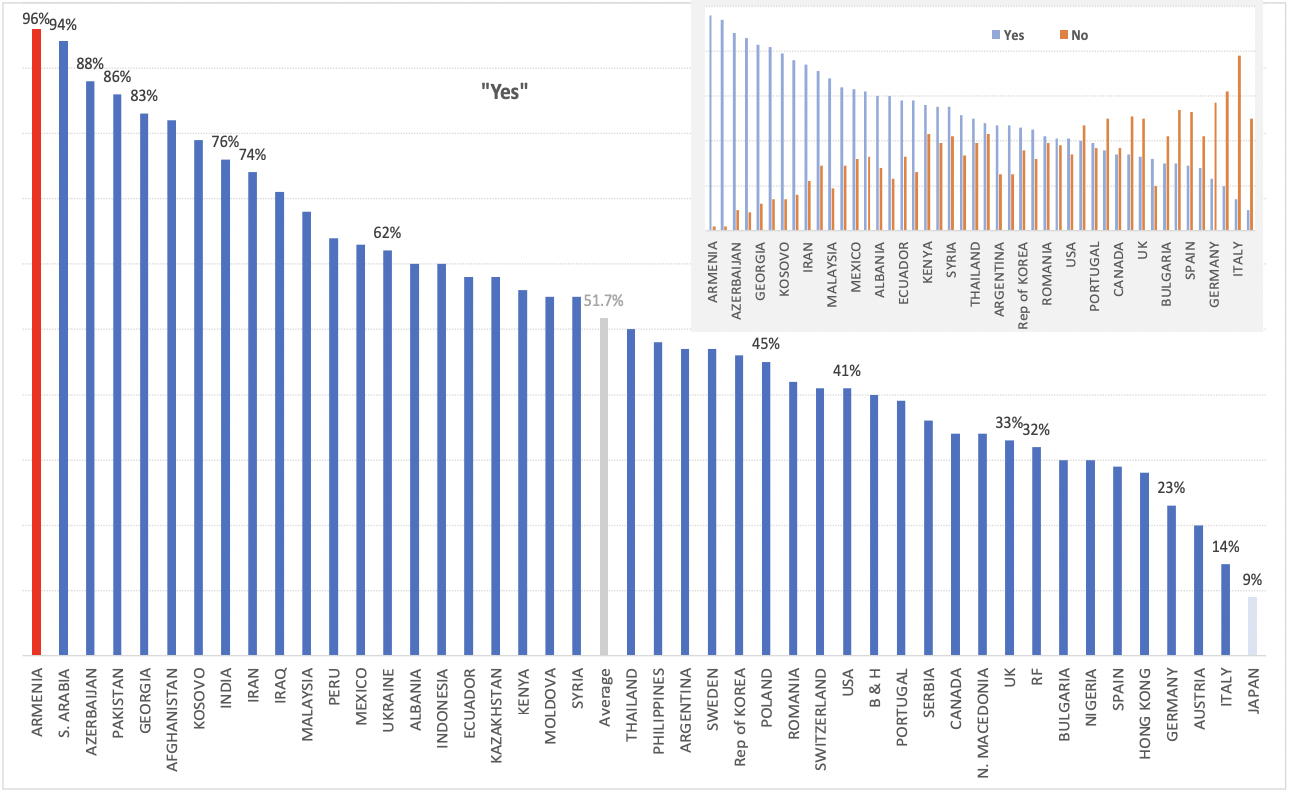

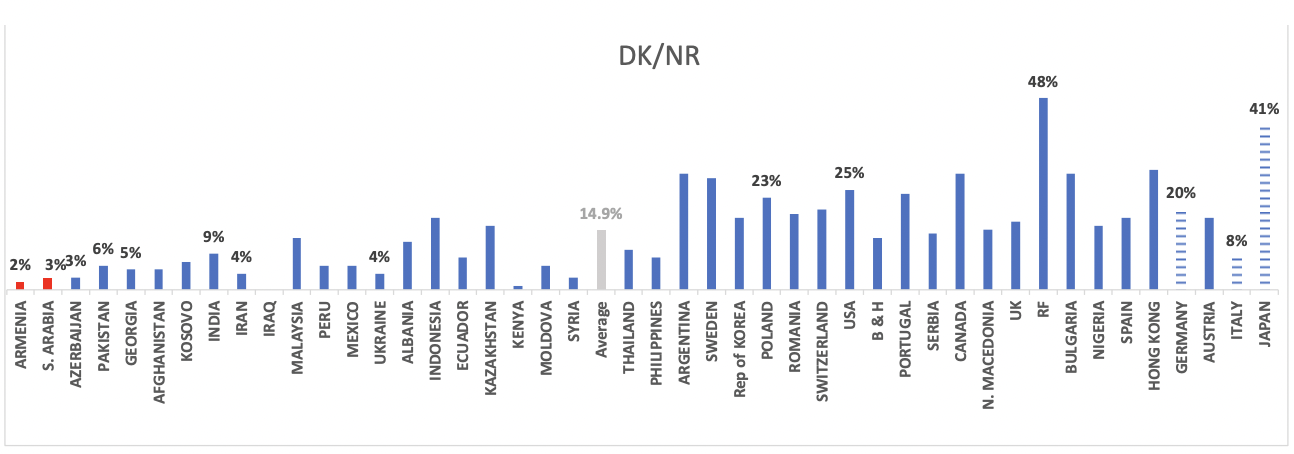

The results of GIA 2023 survey [1] we summarized in three charts, depending on the answers: affirmative (“Yes”), negative (“No”), and uncertain “Don’t know/No response” (DK/NR)(16).

Ch. 1 shows the percentage of respondents answered “Yes” for all considered 45 countries of GIA 2023 survey. It is important to stress that this chart is ranged in a descending order. That is, the order of countries along the axis X of the Ch. 1 follows a decreasing percentage of an affirmative answer to the given question (in [1] results are given in English alphabetical order). Among the countries X axis, the average result of “Yes” answer (51.7%) can be seen, as if it were a separate “average” country covered by the survey. We have corrected minor errors made in [1], while calculating the averages of the answers.

As we can see, at the end of 2023, Armenia, with a 96% of affirmative answer to the question, took first place among all 45 countries covered by survey. The second place was held by Saudi Arabia (94%), followed by Azerbaijan (88%), Pakistan (86%) and Georgia (83%). These top five countries are characterized by a significant, almost twofold, excess of the “Yes” answers over the average value (51.7%, Ch. 1).

Chart 1. Percentage of “Yes” answers (%). The order of countries follows descending of the “Yes” answers (%). In the window – graphs of “Yes” and “No” answers, plotted over the fixed order of countries by descending of “Yes” answers. GIA 2023 EoY Survey.

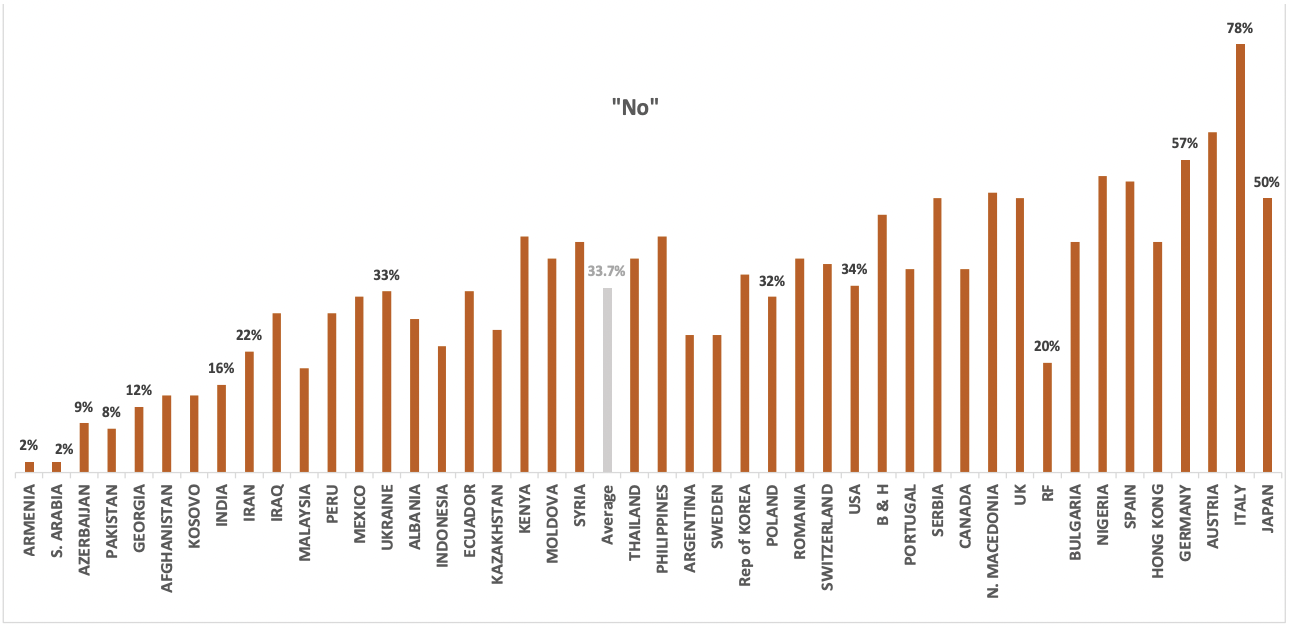

At first glance, it seems natural that charts of negative and uncertain answers should also be built up in the form of ranged charts with descending percentage of “No” and “DK/NR” answers respectively. After all, this is how the public opinion surveys results are usually presented. However, based on reasons that will became clear below, we intentionally preserve the order of countries for “Yes” answers of Ch. 1 also for the Ch. 2 of negative and for Ch. 3 of “uncertain” answers.

Firstly, it is important to note, that the top 5 countries of Ch. 1, are at the same time the very countries, were “No” answers were significantly lower than the average value of the “No” answers (see Chart 2). For example, for Armenia and S. Arabia “No” answers were only 2% and 3% respectively, which is about 10 times less than the average “No” answer (34%, see Ch. 2)(17). Correspondingly, the “uncertain” answers for top 5 countries of Ch. 1 were significantly lower than the average “DK/NR” answer for all 45 countries (15%, see Ch. 3)(18).

Secondly, we want to stress, that Ch. 2 of “No” answers, built upon the sequence of countries in Ch. 1 of “Yes” answers, and not ranged by the descending percentage of “No” answers, however, looks like ranged by descending of “No” answers. Geometrically speaking, Ch. 2 looks like a mirror reflection of Ch. 1 (we emphasized this in the window of Ch. 1). This is by no means a trivial result, and one could not expect such a thing A priori.

The fact that the order of the countries in Ch. 1 for “Yes” answers, demonstrates a “geometric meaning”, also for the Ch. 2 of the “No” answers, indicates that the survey results have an inner “physical”, meaning and in a sense are consistent.

Chart 2. Percentage of “No” answers (%). The order of countries as in Chart 1.

That is, we see a picture, where countries with a significantly higher percentage of “Yes” answers, compared to the average, are also countries with a significantly lower percentage of “No” answers, compared to the average. A similar, but more blurred, picture is also noticeable on Ch. 3 of “DK/NR” answers, which, is also built up for the order of the countries of Ch. 1.

In other words, those results of GIA 2023 survey which are related the question “Will you fight for your country”(19) demonstrate inner consistency, reflecting the degree of “determination” of the countries (more precisely, the respondents) to fight for their country. And the order of countries ranged by the descending of “Yes” answers, retains some “invariant” meaning for other two charts as well. This makes us assume that behind the “linear” picture of Ch. 1, 2 and 3, hidden is a richer picture of countries configuration, than that which is revealed by a simple ordered graph. Thus, further analysis to identify this picture is expedient, and we will try to do it in our next article on this subject.

Let us return to the preliminary analyses of the results.

Chart 3. Percentage of “Don’t know / No response” answers (%). The order of countries as in Ch. 1.

All three countries of the South Caucasus are in the top 5 list of Chart 1. This fact, in our opinion, indicates, high intensity of passions in our region in 2022-23, and high level of determination to fight for their countries. The geopolitical instability of the region, superimposed on “rich” history of confrontation and conflicts, mobilizes societies of the South Caucasus countries for armed struggle. The presence of Saudi Arabia and Pakistan in the top 5 list, as well as of Afghanistan, adjacent to them (6th in the Ch. 1), complete the picture of the boiling “Greater Middle East” (20), highlighting the South Caucasus region even against this turbulent background.

On the other side of the Ch. 1, among the last five countries least willing to fight for their country, we see Germany (23% “Yes”), Italy (14%) and Japan (9%), and among them Austria (20%). One cannot help to noticed that these are the countries of “Axis” of the WWII, plus Austria, annexed by Germany in March, 1938.

Finally, the survey results for Russia, obtained at the end of 2023, appear somewhat unexpected. Only 32% of respondents answered “Yes” to the given question, which is noticeably below the average (52%, Ch. 1) for all 45 countries covered by the survey. However, only 20% gave a negative answer, which is also below the average (33%, Ch. 2). Meanwhile, 48% of respondents in Russia were “uncertain”, which is about 3.5 times higher than the average (14%, Ch. 3). In fact, this is the maximum value in Ch. 3, with Japan’s 41% second-highest level, only slightly lower, but still exceptionally high above the average (14%).

For Ukraine, the 2023 survey recorded 62% “Yes”, 33% “No”, and only 4% “DK/NR” answers. Thus, according to [1], the “determination” of Ukrainians to fight for their country is almost twice as high as the determination of Russians. But of course, unusually high levels of “DK/NR” answers for RF and Japan still need some explanation, unfortunately absent in [1]. One can only speculate that these is due to some degree of restraint of the respondents, caused by the ongoing Special Military Operation (SMO) of RF in Ukraine, and due to still unresolved situation between RF and Japan over “the Northern Territories”.

It is interesting to note, that the level of emigration from Ukraine after the beginning of the SMO is estimated at about 10 mln persons, which comprise about 4.20% of the total population (42 mln) of Ukraine in 2014. Meanwhile, emigration form RF after the beginning of the SMO is estimated up to 1.0 mln persons, which is only about 1.44% of the total population (144 mln) of RF in 2014.

SOURCES AND REFERENCES

- 2023 EoY Survey. Fewer people are willing to fight for their country compared to ten years ago. 25 March, 2024. https://www.gallup-international.com/survey-results-and-news/survey-result/fewer-people-are-willing-to-fight-for-their-country-compared-to-ten-years-ago

- A. H. Marjanyan, The scientific-information policy and hybrid wars. “21st CENTURY”, #4 (74), 2017. http://www.intelros.ru/pdf/21vek/201704/2.pdf

- A. H. Marjanyan, THE UNIVERSE OF WORDS։ The Google N-grams tool and frequency of the usage of words (in Arm.), “21st CENTURY”, #4 (74), 2017. https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/vselennaya-slov-google-n-grams-i-chastota-ispolzovaniya-slov.pdf

- A. H. Marjanyan, Jean Baudrillard’s “Simulacres” and Barak Obama’s “Medz Yeghern” (in Arm.), P. 2 “May, 1968”, “21st CENTURY”, #4 (74), 2017.

(1) UNDP National expert (power sector), EU National expert (transport), EAEC Expert Club fellow, Ph.D., Senior Scientific Researcher, Leading analyst.

(2) Translated from Russian. The Russian original was submitted to the Editorial Board on 10.05.2024.

(3) “I’m begging you”, from the book “Man in palm”, 1957.

(4) “Global Barometer on Hope and Despair”. Also named “End of Year Survey (EoY)”.

(5) Previously it was “ROMIR” company that conducted surveys in Russia on behalf of GIA [2].

(6) “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest”, “John Wesley Harding” album, 1967.

(7) In Russian, Если бы была война, в которой втянута (ВАША СТРАНА), будете ли вы готовы сражаться за свою страну?», In Armenian, «Եթե պատերազմ լիներ, որին ներքաշված է (ՁԵՐ ԵՐԿԻՐԸ), ապա պատրաստ կլինեի՞ք կռվել ձեր երկրի համար».

(8) Article 51, “Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security”. Chapter VII of UN Charter: Actions regarding threats to the peace, breaches of the peace and acts of aggression (Articles 39–51).

(9) There are about 5 thousand living languages in the world. Google corpuses have been created for only seven of them (German, French, Spanish, Russian, Chinese, Hebrew and several corpuses for English), for more details, see.[3].

(10) Let’s pay attention that the Russian “rodina” comes from “rod” (genus, race, family in large), English “homeland” from “home”, Russian “otchizna” from “otche” (father), just as in the Armenian “hayrenik”, or English “fatherland”, German “vaterland”, Spanish and Italian “patria»” etc.). From all these we have “patriotism”, “The Patriot” film or the “Patriot” surface-to-air missile system.

(11) Corpus linguistics, English, fiction, 2019.

(12) To compare։ before 2010, the best linguistic frequency corpuses (English, French, Spanish) counted only a couple millions of words. The first (and the last) “Dictionary of word frequency of contemporary Armenian language”

(by B. K. Kazaryan), published in 1982, counted only 36 thousand words [3].

(13) After all, our Anglo-Saxon friends say “homeland security”, but not “country security”, or “fatherland security”. Even more reviling pictures emerges when analyzing the German corpus, or when simultaneously analyzing the English and German corpuses for the words “fatherland” and “Vaterland” etc, but we will omit all this here.

(14) Détente [French]. The policy of easing international tension, the policy of “peaceful coexistence”.

(15) We stated once, that “creating of the Armenian language corpus is a task no less important, than creating another “Panzer Corps” [3].

(16) Hear and everywhere later we combine “Don’t know” answer of the survey with “No response” results in a single “uncertain” category “DK/NR”.

(17) The average value of answers “No” in [1] is given as 33%, while the correct number is 33.7%, see Chart 2.

(18) The average value of “uncertain” answers in [1] is given as 14%, which is incorrect. The sum of “Yes”, “No”, “DK/NR” answers may slightly differ from 100% due to rounding errors.

(19) The GIA EoY 2023 survey touches many other issues.

(20) Unfortunately, the Israel and Palestine were not covered by the GIA EoY 2023 survey.