On the basis of the Azerbaijani position about the “territorial claims of Armenia recorded in the Constitution of the RA”

Expert’s comment, 08.08.2024(1)

Norayr A. Dunamalyan(2)

The present Azerbaijani policy is largely based on “reverse” propaganda, projecting the reasonable criticism of the destructive actions of the Azerbaijani authorities on their opponents, in particular – on Armenia. I. Aliyev’s demands to change the Constitution of the Republic of Armenia are based on this very logic and reflect the political and legal shakiness of the Azerbaijani statehood foundations and the manipulation of the concept of “territorial integrity”.

The path to the modern Republic of Armenia’s independence was set by successive steps taken in the spirit of the “Perestroika” policy and, as it seemed to many figures of the Karabakh movement, in accordance with the accepted “rules of the game”, be it the USSR Constitution or the post-Soviet settlement. Meanwhile, Baku alternated between two mutually exclusive tendencies: an anti-Soviet and a conditionally “pro-Soviet” position. While the Armenian side explicitly raised the issue of NKAO’s self-determination, Baku tried to maneuver between the Soviet Union center and liberal-nationalist circles within the republic. However, it was Azerbaijan that began the gradual process of breaking the Soviet “rules of the game”.

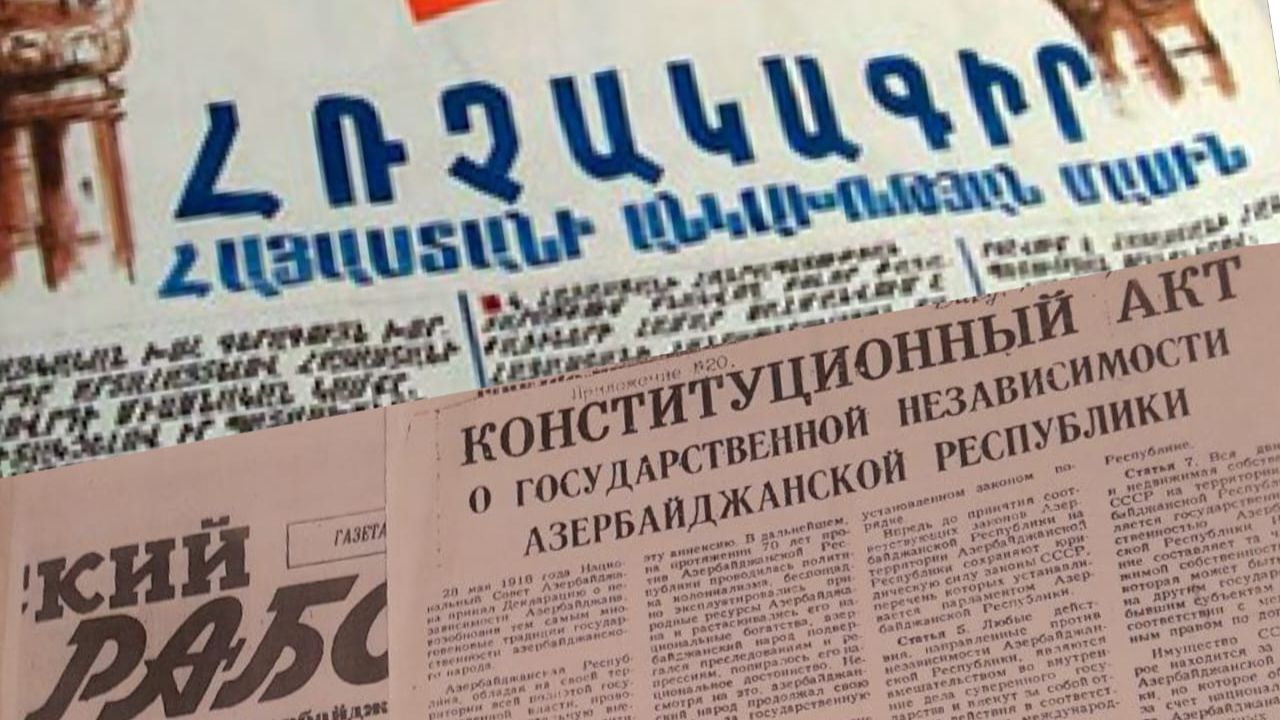

The “Resolutions of the Supreme Soviet of the Arm. SSR and the National Council of Nagorno-Karabakh on the reunification of the Armenian SSR and Nagorno-Karabakh”, adopted on December 1, 1989, did not constitute a claim to the territory of Azerbaijan because, first, the issue of transfer of the subjects of the USSR was raised within the logic of a single territorial-political entity, and secondly, on September 23, 1989, the Supreme Soviet of the Azerbaijan SSR adopted the “Constitutional Law of the Azerbaijan SSR on the Sovereignty of the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic”, which proclaimed the real independence of Azerbaijan. At the same time, throughout 1989 there was a “war of resolutions” over Nagorno-Karabakh, initiated by the Union Center and the Azerbaijani leadership, which violated the constitutional rights of the local population and deprived them of representation in state bodies. By adopting the law on sovereignty (while the All-Union law on holding referendums was adopted only in December 1990), the Azerbaijani authorities tried to blackmail the Union Center in order to obtain its support for the violent settlement of the Karabakh conflict. This approach would be repeated several times in the future.

It was only on August 23, 1990 that Armenia adopted a Declaration of Independence, one element of which was the “Resolution on the Reunification of Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh”, which was a political statement demonstrating the commitment to protect the right of the people of Artsakh for self-determination. The Azerbaijani interpretation of this aspect, linking the Resolution with Armenia’s alleged territorial claims against Azerbaijan, continues the old narrative of “occupation of Azerbaijani lands”, ignoring the rights of Armenians who were subjected to ethnic cleansing in 1988–1993 and 2020–2023. However, even in the case of the refusal to mention the “Declaration of Independence” in the preamble of the RA Constitution, the satisfaction of such demands is a dangerous precedent (also for Azerbaijan).

As it has already been noted, the Karabakh issue became an element of political games between the leadership of the AzSSR and the Union Center, and until August 30, 1991 (and even until the collapse of the USSR), Azerbaijan tried to get Moscow’s support to settle the conflict by force. In February 1991, the Supreme Soviet of the AzSSR bypassed the Constitution of the USSR and renamed the country as the Republic of Azerbaijan, which did not prevent Azerbaijan from participating in the referendum on the preservation of the USSR in March 1991 (when more than 90% of the Azerbaijani participants voted in favor of preserving the Union), and in May of the same year the Azerbaijani leadership agreed to participate in the so-called “Novo-Ogaryovo process” aimed at preserving the Soviet Union in the form of a confederation. At the same time, in April-May 1991, the Azerbaijani OMON (heavily armored Police Special Detachment), supported by units of the Soviet Army, the Ministry of Interior and the KGB of the USSR, carried out ethnic cleansing in Nagorno-Karabakh (NKAO and the Shahumyan region) and Armenia (the so-called “Operation Ring”, also Operation “Koltso”). On August 19, the leader of Azerbaijan A. Mutalibov even supported the coup attempt of the State Committee on the State of Emergency (SCSE), but after the “August putsch” the Azerbaijani leadership radically changed its approach, abandoned the Soviet legacy and adopted a declaration on the restoration of independence (August 30) and then a constitutional law “On the State Independence of the Republic of Azerbaijan” (October 18). These documents confirmed the continuity of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic of 1918 (with its undefined state borders), as well as noted the illegality of Soviet decrees concerning Azerbaijan, accusing Russia of annexation and occupation of Azerbaijan (twice: in 1806-1828 and 1920). By this step, Azerbaijan, among other things, renounced the political and legal basis for the creation of the Autonomous Oblast of Nagorno-Karabakh (since 1936 – Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO)).

This historical excursion allows to understand the logic of Azerbaijan’s territorial claims, which are largely opportunistic and do not imply any grounds. The same wording in the declaration of independence of Azerbaijan, according to which the territory of Azerbaijan includes South and East Transcaucasia, is a nonsense, which was not corrected even at the time of the current independence. On the other hand, the recognition of the Soviet borders is also problematic for Baku, since Azerbaijan, having held a referendum on secession from the USSR on December 29, was essentially withdrawing from a non-existent entity. Moreover, the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic declared its independence from Baku on September 2, 1991 – long before Azerbaijan adopted the constitutional law “On the State Independence of the Republic of Azerbaijan”. At the same time, the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic applied all the necessary procedures provided by the Soviet legislation, and the abolition of the NKAO by the Supreme Soviet of Azerbaijan was recognized as unconstitutional by the resolution of the Constitutional Supervision of the USSR dated November 28, 1991.

In other words, Azerbaijan has never defined the boundaries of its state: neither in the case of its First Republic (the League of Nations did not recognize the borders of the ADR due to territorial disputes with the neighboring states), nor the “Soviet” borders, as the nowadays Azerbaijan rejected the Alma-Ata Declaration and abolished the autonomy of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Nevertheless, Azerbaijan can use both the argument of the “flexible borders” of the ADR and the “demarcation” based on the Soviet maps. In both cases, the Azerbaijani authorities rely on force and economic leverage rather than political and legal arguments. In comparison with the continuity of Russia from the USSR, in the Azerbaijani “expert” community itself, the issue of succession from First Republic is not considered as an important issue from the territorial point of view. However, it should be remembered that the Constitution of the RF does not refer to any document of the Soviet or the Imperial period, while the Constitution of Azerbaijan contains a reference to the Fundamental law on independence, which notes the restoration of the pre-Soviet regime and thus touches upon the paragraphs of the 1918 Declaration, which contain territorial claims to Georgia and Armenia. This circumstance brings us back to the decision of the League of Nations not to recognize ADR because of territorial disputes.

Baku, which uses quasi-historical narratives to exert pressure, may receive the answer in the form of an “appropriate” response from regional opponents. Under certain conditions, Armenia can make demands regarding the wording of the Eastern and Southern Caucasus in the ADR Declaration of Independence, the issue of the “occupation of Azerbaijan” by Russia, the illegality of the abolition of the NKAO and the fact of the destruction of the Armenian cultural heritage. In other words, the manipulation of Azerbaijan aimed at creating myths about the affiliation of Armenia to the “historical Azerbaijan”, etc. makes it necessary to refer to the history of territorial separation of 1918–1920 when the territory of Azerbaijan had no recognized borders. Thus, appeals to disputed historical documents as an argument for territorial claims can open the “Pandora’s box” and lead to mutual accusations of 100 years ago.

“Territorial” narrative has been consistently exaggerated by the Azerbaijani side, although the Nagorno-Karabakh issue originally had and still has a territorial-legal character of the struggle of the Nagorno-Karabakh/Artsakh Armenians for the final self-determination in their region of origin. Therefore, the accusations of Armenia of “aggression against the territories of Azerbaijan” are used by the Azerbaijani leadership to destroy the pro-Armenian narrative related to the aggression of Azerbaijan against the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, violation of the rights of the Armenian population (including the right to life, liberty and property), ethnic cleansing, etc. It is necessary to perceive the problem of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict settlement as an urgent issue, even though the Armenians have been expelled from Artsakh. At the same time, the Aliyev regime is trying to make this confrontation historic by calling for a change in the RA constitution and the dissolution of the OSCE Minsk Group. Therefore, it is important not to fall into the “trap” of only “territorial” logic of relations, ignoring legal and cultural aspects.

The problems of constitutional organization of Azerbaijan, if not to go deep into the “peculiarities” of separation of powers or formulations of the fundamental document of this state, concern, first of all, maintenance of I. Aliyev’s personal power of regime. This fact makes it impossible to formulate more universal “rules of the game”, which will be acceptable for the next authority. For example, the constitutional role of the vice-president in case of a change of power in Azerbaijan may become the basis of political crisis, as there may be a conflict with country’s prime minister over the exercise of presidential powers. There are also other controversial points in the Azerbaijani constitution, but more importance is attached to the strengthening of the regime, even at the price of ignoring strategic issues. It is obvious that the political regime of Azerbaijan is structured as a hereditary autocracy, which implies an aggressive attitude towards the neighboring states and situational actions of the elites. However, the Aliev dynasty managed to subjugate all state institutions, also using political narratives necessary for the reproduction of power, for example, softening the anti-Russian orientation of the Declaration of Independence of Azerbaijan (H. Aliyev cult, modern relations with the Russian Federation, etc.). But at the same time, it must be noted, that the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region existed in the “totalitarian” USSR, but is ignored by the current “democratic” authorities of Azerbaijan, and all historical and cultural traces of Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh are now consistently erased.

Contrary to the claims of the “leadership” of Azerbaijan in the South Caucasus, there is a situation of continuous destabilization of the regional security, which depends not on the institutional structure of relations between countries, but on personal relations of heads of the states. In this context, weak institutionalization of power leads to a strong influence of the desires and complexes of state officials on international relations, which in turn leads to unpredictable processes and increased threats. The instability of the state foundations forces Azerbaijan to undermine the political institutions of other countries of the South Caucasus and contribute to their vulnerability, seeking to maintain the stability of its state based on profits from the extraction and transit of hydrocarbons, while in the long run it is a path to chaos, rather than peaceful coexistence.

(1) The original (in Rus.) was posted on our website on 05.08.2024.

(2) Candidate of Political Sciences, Associate Professor of the Department of Political Science at the Russian-Armenian (Slavic) University. Author of more than 20 scientific papers and articles.