Publication

Foreign policy dimension of the upcoming parliamentary elections in Armenia

Expert commentary, September 22, 2025[1]

Norayr A. Dunamalyan[2]

The parliamentary elections in Armenia scheduled for June 7, 2026, promise to be a pivotal event in the context of society’s acceptance of post-war realities and the final shift in geopolitical orientations. In any case, the main theme of the upcoming campaign will be the choice of the country’s “geopolitical future”, which is a novelty for the entire electoral agenda of the post-Soviet period.

Internationalization of Armenian domestic policy

Following the defeat in the 44-day war of 2020, the political discourse in Armenia gradually shifted from discussing models of internal development to revising geopolitical orientations. While the 2021 parliamentary elections were still interpreted as a confrontation between the “current” and the “former” elites, symbolizing a supposed division between the “authoritarian past” and the “democratic present”, their substantive basis remained within the traditional post-Soviet agenda: the fight against corruption, social inequality, democracy, and authoritarianism.

The introduction of a Russian peacekeeping contingent to Nagorno-Karabakh in November 2020, the preservation of the OSCE Minsk Group, and Turkey’s growing influence in the South Caucasus signaled a trend toward the internationalization of political processes around and within Artsakh. However, the military actions on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border in September 2022, the ethnic cleansing, and the subsequent occupation of the NKR in 2023 transferred this trend directly to the territory of the Republic of Armenia. Domestic politics came under the direct influence of external actors, which became a prerequisite for the transformation of the entire Armenian political system.

As a result, the political reality that formed after the 2021 elections has largely lost its relevance, as have many of the foreign policy platforms of both the government and the opposition. A characteristic example is the pre-election formula of “Remedial Secession” for Nagorno-Karabakh, which was never practically implemented. The 2023 crisis marked the beginning of a radical reconfiguration of the political system: in the public perception, socio-economic problems gave way to issues of territorial integrity and national security, which are directly dependent on the republic’s geopolitical choice (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The main problems faced by the population of the Republic of Armenia (the following responses of respondents: “borders”, “lack of peace” and “unresolved territorial disputes” are combined in the indicator “Peace and security issues”). Source: https://caucasusbarometer.org/en/cb-am/IMPISS1/

On the other hand, following the September 2022 aggression, Western political presence began to take on a new, institutionalized form. Thus, the EU attempted to portray itself as a mediator in the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict and used the pretext of de-escalation to send a monitoring mission to Armenia. At the same time, humanitarian support and political statements from European representatives intensified, giving the “European vector” real weight in domestic policy. The United States, despite changes in administrations, deepened its presence in the region by concluding the U.S.–Armenia Strategic Partnership Charter and the Washington Memorandums in 2025. The Russian factor, conversely, acquired a negative connotation, turning the “main strategic ally” into a subject of domestic political debate. Consequently, the government continues to distance itself from Russian influence, using narratives such as the “hybrid war against Armenia”, while the opposition cautiously tries to use pro-Russian rhetoric, although it no longer consolidates the electorate.

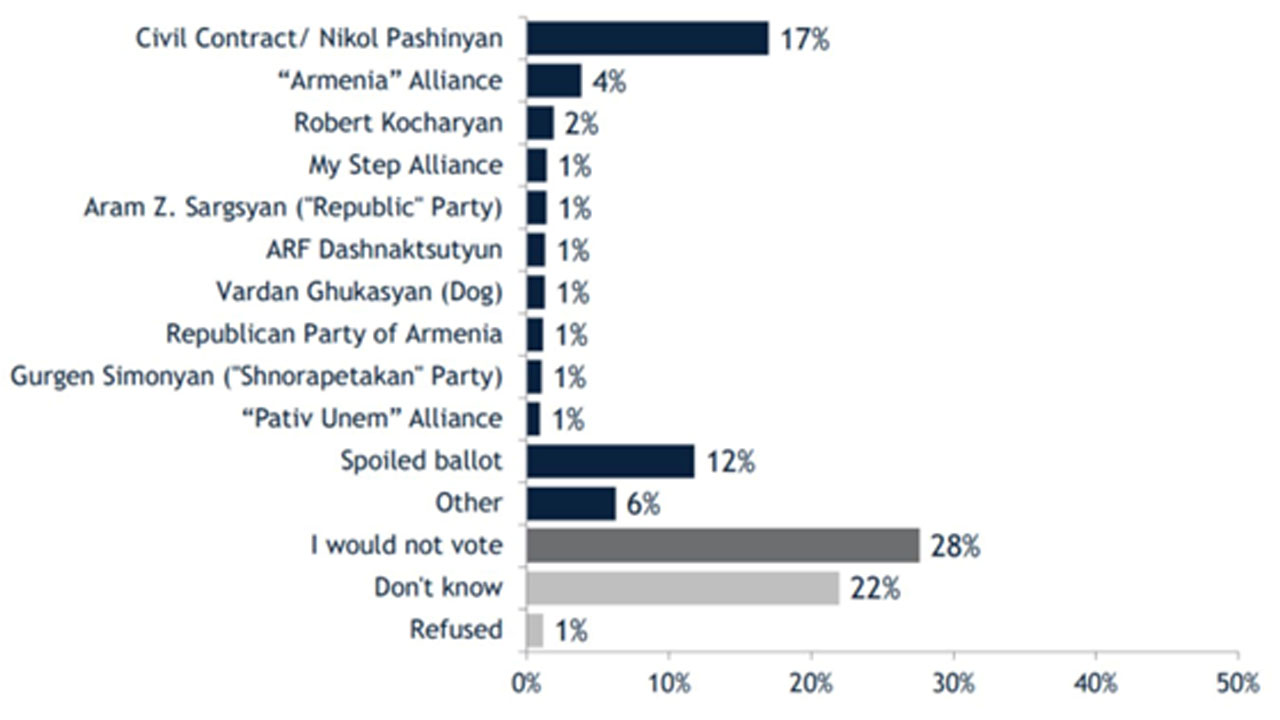

Notably, Azerbaijan has been systematically exerting active influence on Armenia’s domestic political situation since 2020, playing on the contradictions and fears of Armenian society and promoting its own narratives. The thesis of removing the reference to the “Declaration of Independence” from the preamble of the RA Constitution has also become a significant lever of pressure on the Armenian government and society, threatening the country’s internal political stability. Ultimately, the future elections may be reduced to a false dilemma between “peace” and “war”. Meanwhile, the ruling party’s interest in low voter turnout in the parliamentary elections (in which case 17% support can be converted into 54% of seats in the National Assembly) clashes with the need for high participation (25% of all eligible voters must vote “For”) in a referendum on constitutional changes to satisfy the latest demands of the Azerbaijani side. Thus, an externally created domestic political “trap” is being formed, reinforcing authoritarian tendencies in Armenia under the pretext of ensuring “peace and security”.

The alignment of political forces and their geopolitical preferences

For almost the entire period of independence, the foreign policy orientation of Armenian elites has been conditional. The republic’s three presidents pursued a policy of complementarism at different times, seeking to maneuver between centers of power to obtain resources and security guarantees. This tactic was accompanied by periodic crises in relations with major powers, primarily Russia.

Until 2022, Russian influence was perceived as a constant, pushing the political forces to seek external legitimacy primarily in Moscow. However, after 2022–2023, the post-Soviet logic of interaction ceased to work. The reconfiguration of regional security and the disappearance of the “Karabakh factor” radically changed the context. The existence of Armenian Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) during the 2021 vote and its absence today changes the entire picture of the future elections, replacing the agenda of “saving the Armenian population of Artsakh” with the issue of “saving Armenia”. The artificial separation of these two aspects is politicized, aimed at justifying the idea of an “era of peace” and narrowing the Karabakh issue to the level of a “historical misunderstanding” between Armenians and Azerbaijanis. As a result, the “Karabakh consensus” that dominated Armenian politics until 2021 is considered irrelevant, and economic, social, and other issues will be overshadowed by the dilemma between “Western/European” path and “peace”.

It’s also worth noting that the apathy that arose after the defeat in the 44-Day War of 2020 could also undergo some unexpected transformations. The low level of support for the ruling party (17%) was characteristic of the post-war reality, but several events occurred in the second half of 2025 that could serve as a catalyst for the authorities’ election campaign (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Distribution of electoral preferences in the Republic of Armenia (July 2025).

Fig. 2. Distribution of electoral preferences in the Republic of Armenia (July 2025).

Source: https://www.iri.org/resources/public-opinion-survey-residents-of-armenia-june-2025/

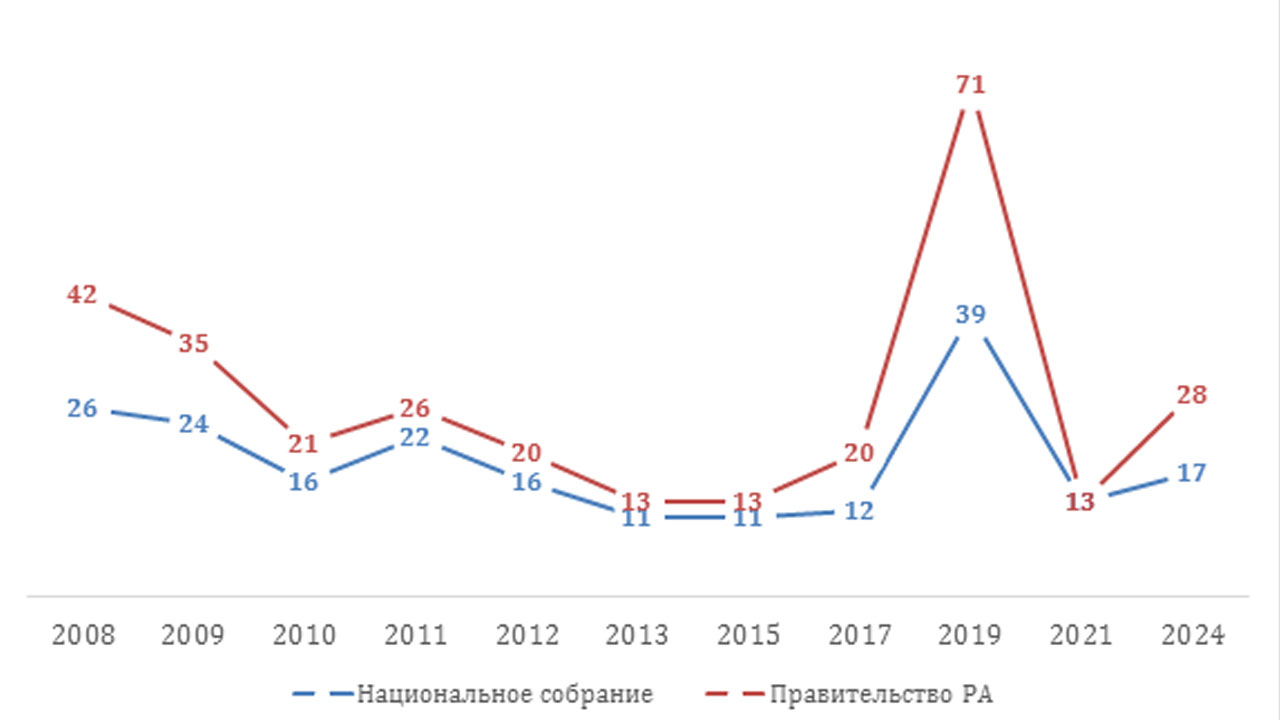

The fact is that the political situation in Armenia after 2018 was “abnormal”. High expectations were formed under the influence of post-revolutionary euphoria, and the defeat in the war created a new anomalous reality with high levels of indifference to political processes and distrust. At the same time, trust in the government and the National Assembly is now at the level of 2010–2012 (Figure 3), which in the past allowed the ruling party to retain power. The “normalization” of the political situation is expressed in the fact that even with a low level of trust, the authorities are able to reproduce their power through administrative resources, electoral passivity, and weak competition. Unlike the period of post-revolutionary mobilization (2018–2020), when the legitimacy of the government was based on mass enthusiasm, today the factor of its stability is institutional control over the election process and society’s habituation to minimal standards of stability.

Fig. 3. Level of trust in the Government and the National Assembly in Armenia, %.

Source: https://caucasusbarometer.org/en/cb-am/

Against this backdrop, the Prime Minister’s election campaign is built on presenting the ”peace agenda” as a fait accompli. However, a clash between inflated expectations and the ongoing conflict could undermine this strategy, as Armenia has virtually no leverage over regional processes. As a result, the isolation of the domestic agenda from international processes reduces the election to the task of preserving power without guarantees of real peace. This leads to a kind of “virtualization” of politics, where categories like “the European path” “enhancing sovereignty”, and “unblocking communications” become declarative. However, a society tired of uncertainty may accept this situation as a means of stabilization, which, in turn, may push the opposition towards more “constructive” steps.

“Normalization” is accompanied by the consolidation of parties loyal to the government. Thus, in 2024–2025, as part of the EU accession campaign, the “Euro-bloc”, which served more of a PR function. Furthermore, the presence of pro-Western (anti-Russian) forces in Armenia’s political landscape significantly expands the ruling party’s room for maneuver. The emergence of a new (conditionally pro-Russian) force led by Samvel Karapetyan – “Mer dzevov” (“In our way”) – also indicates a renewal of the political landscape, but the ruling elite remains the primary moderator of these processes.

Other opposition parties face the problem of reconfiguration. The conflict between the “Armenia” bloc and the Republican Party hinders their consolidation, although both structures are traditionally considered pro-Russian. The most clearly pro-Russian position today is expressed by the supporters of R. Kocharyan. The “Dashnaktsutyun” party combines harsh opposition to the current government with a course of maintaining a strategic alliance with Russia and concluding an alliance treaty with Iran, turning radical rhetoric into an instrument of institutional struggle.

Thus, foreign policy is seen as a resource in domestic political struggle, which, in turn, allows other countries to influence the electoral process in Armenia and its politics as a whole.

Sources of external legitimacy

The August summit in Washington can be seen as an important source of external legitimacy for the current government, logically fitting into the peace agenda and the discussion of the republic’s economic future (unblocking communications). The fact is that the parties to the conflict had different interests in initialing the peace treaty and agreeing to the “Trump Path”. In short, the Armenian side sought to use the summit’s results in its election campaign, while Baku aimed to use it to increase pressure on Armenia if necessary and to mobilize its population around another foreign policy “victory”. However, both agendas are intertwined in the context of the upcoming elections in Armenia, as Baku links the final signing of the peace treaty to changes in the RA Constitution.

Notably, the establishment of contacts with Turkey is being used by the Armenian authorities as an additional political resource in the election campaign. However, this strategy increases Yerevan’s dependence on the Turkish-Azerbaijani tandem. If in the past Ankara directly linked the opening of the border to the settlement of the Karabakh conflict, today this linkage has become more complex: the Armenian leadership’s attempt to convert improved relations with Turkey and Azerbaijan into domestic political capital is embedded in the general context of trilateral relations, where Armenia remains the weakest link.

Paradoxically, relations with France and India, which were emphasized as part of Armenia’s foreign policy diversification, have now receded into the background, and political interaction with Iran is not being promoted in the context of the domestic political struggle.

Thus, external legitimacy in the upcoming campaign is formed through symbolic and institutional rapprochement with the West, as well as attempts by the authorities to use the normalization of relations with Turkey and Azerbaijan as confirmation of their “peace agenda”. However, it is the Russian factor that requires separate consideration. Unlike the EU and the U.S., which are strengthening their institutional presence, or Turkey and Azerbaijan, which are active moderators of the regional processes, Russia has transformed from a strategic ally into a variable, that causes sharp domestic political disputes and has become a factor in the revision of the traditional model of complementarism.

The symbolic meaning of the Russian factor

The Russian factor in Armenian politics today has largely lost its practical basis but retains an important symbolic dimension. For part of society and the opposition forces, Russia continues to be associated with a “traditional ally” and a guarantor of security, even if this status is gradually changing. For the government, distancing from Moscow becomes a symbol of a new course, a demonstration of “sovereignty” and an orientation towards the West.

In the election campaign, Russia is more of a marker of political identity than a real source of resources:

- For the ruling party the appeal to “break with the past” and criticism of dependence on Moscow strengthens the image of a reformist and pro-Western choice,

- For the opposition, maintaining pro-Russian rhetoric serves as a way to emphasize continuity, stability, and criticism of the risks of “geopolitical experiments”.

The decline of Russian influence is also evident at the institutional level: the role of the CSTO and the EAEU in political discourse is minimized, and official contacts are increasingly formal. At the same time, the Russian side retains the potential to influence RA through energy dependence, labor migration, and trade, which turns it into a “hidden factor” in the election campaign.

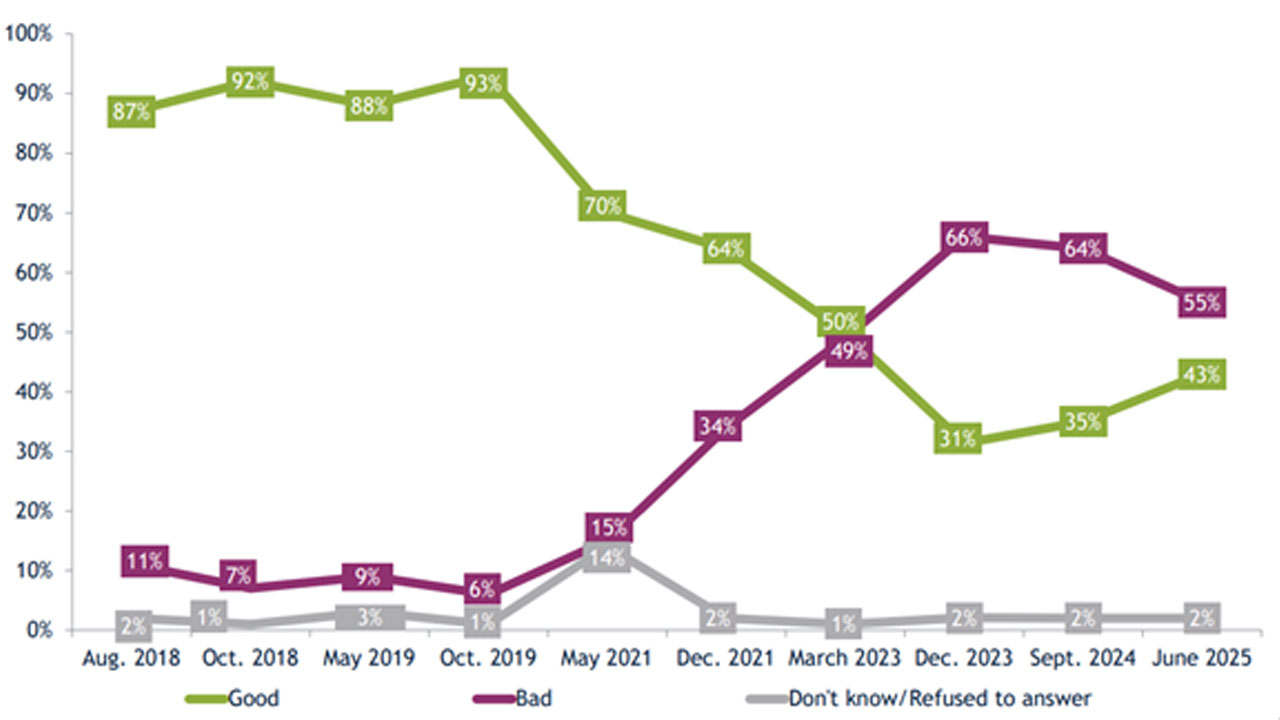

According to sociological surveys, the electoral appeal of pro-Russian slogans has sharply declined: while they previously provided a broad electoral base, today they are perceived more as an appeal to the past than a realistic strategy for the future (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Assessment of Russian-Armenian relations, %.

Source: https://www.iri.org/resources/public-opinion-survey-residents-of-armenia-june-2025

However, it is worth noting that attitudes towards Russia show a positive trend compared to previous years, indicating the potential for “normalization” of this indicator in the future.

Thus, in the upcoming 2026 elections, Russia for the first time appears not so much as a source of legitimacy but as a challenge to the Armenian elites: the government is forced to justify the need to reassess Armenian-Russian relations, while the opposition is forced to demonstrate the possibility of preserving the union. In both cases, the Russian factor ceases to be a source of consensus and becomes a dividing line within the political field. Therefore, Russia will likely adopt a more cautious tactic and refrain from directly influencing the elections in order to maintain stable (albeit problematic) relations with the Armenian leadership.

Hidden actors

Alongside the obvious external players – the U.S., the EU, Russia, Turkey and Azerbaijan – Armenia’s internal political processes are shaped by hidden actors whose role is often underestimated but has long-term implications for the upcoming elections.

The Diaspora continues to be a significant resource of political and symbolic influence. Modern divisions within the Armenian diaspora, reflecting historical traumas, ideological differences, and different approaches to foreign policy, create a complex system of interaction with Yerevan. Public campaigns, lobbying in international organizations, and the shaping of the narrative of “Armenia’s security” allows the Diaspora to participate in shaping the domestic political agenda while remaining an “invisible” player.

International financial institutions are creating the country’s economic dependence. Growing public debt and the need to comply with creditors’ terms limit the autonomy of the Armenian government in economic and social decision-making, transforming the economy into an instrument of political pressure. Political decisions on infrastructure, social programs, and budget allocation are partially conditioned by external financial requirements.

The Church, as a network institution with high social and cultural legitimacy, also acts as a significant actor. Since 2020, the Armenian Apostolic Church has actively used its status for political rhetoric, criticizing the Government’s actions and putting forward its own vision of the “national interest”. In turn, the state’s attempts to limit the Church’s influence demonstrate that this institution has become a factor in domestic political competition and the shaping of public opinion.

Thus, hidden actors, combining symbolic, economic, and cultural influence, create an additional dimension to Armenia’s domestic political dynamics. Their impact intersects with official foreign policy lines and increases the complexity of decision-making for the authorities, forming an additional layer of uncertainty for the 2026 election campaign.

Conclusion

The geopolitical choice is inevitably linked to a socioeconomic dimension. Dependence on Russian energy resources and the market as a whole is pitted against the prospects of European investment and American support. However, for most citizens, this dilemma remains largely symbolic: living standards and social security depend on domestic policy, while foreign policy debates are perceived as a battleground for elite struggles. The difference in perceptions of the political process among different generations of Armenian citizens also contributes to the fact that the outcome of the vote could be quite unexpected, since, unlike the elderly, young people suffer less from the post-Soviet “ailment” of geopolitical choice.

Moreover, the 2026 elections are becoming not just a competition between parties, but a struggle for the interpretation of Armenia’s future – between virtualized promises of peace and the reality of a protracted conflict, between the “European vector” and the search for new guarantors of security, between the hope of modernization and the risk of authoritarian drift. Ultimately, due to low internal legitimacy, the ruling regime, as well as the opposition, are seeking a source of stability from outside, thereby deepening the vulnerability of the Armenian state.

[1] The original Russian article was submitted to the Editorial Board on 17.09.2025.

[2] Candidate of Political Sciences, Associate Professor of the Political Science Department at the Russian-Armenian (Slavic) University. Author of over 15 scientific papers and articles.