Publication

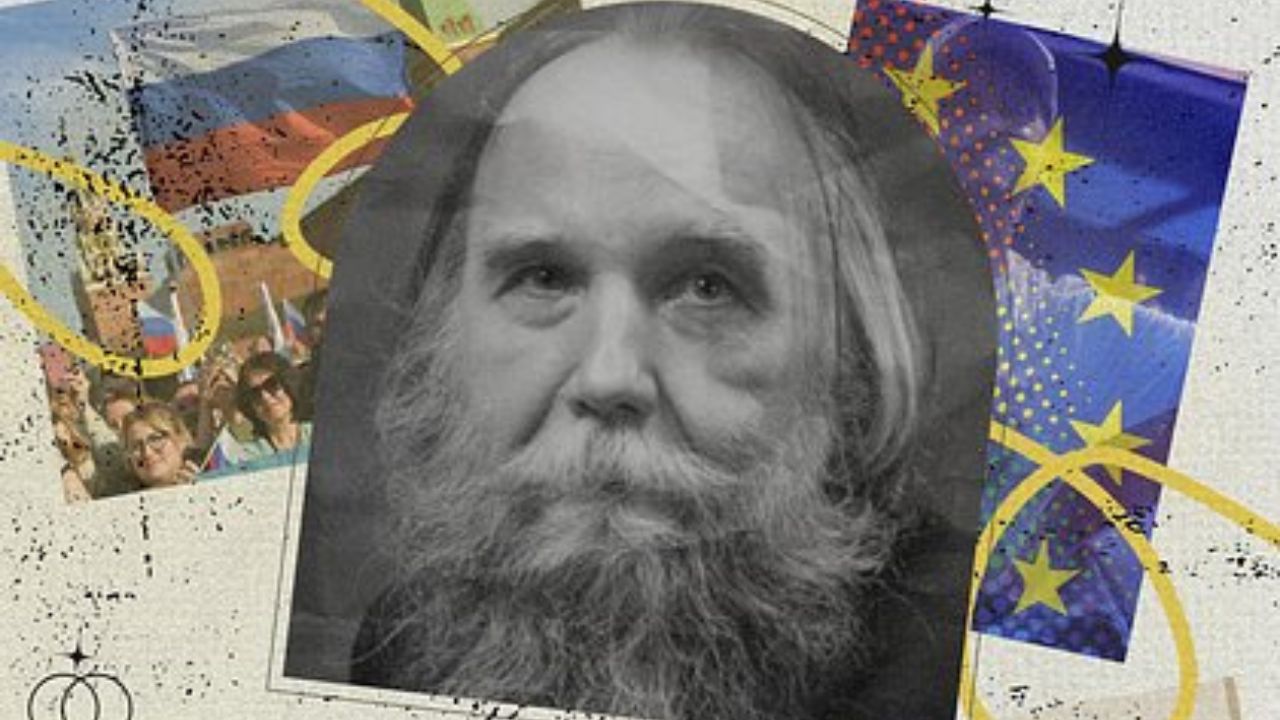

The Decline of Dugin’s Eurasianism

Summary

This article examines the context of Russian philosopher Alexander Dugin’s open letter to Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev in May 2025, concerning the arrests of the “Azerbaijani Eurasians”. Dugin views these arrests as a blow to the Eurasian “Moscow–Baku Axis”. The article explores the ideological foundations of Dugin’s concept of Eurasianism, its distinctions from classical Eurasianism, and the influence of its tenets on the foreign policy of Russia. It analyzes Azerbaijan’s geopolitical significance as a link to Central Asia within the frameworks of H. Mackinder’s and Z. Brzezinski’s concepts, as well as Dugin’s own conceptual apparatus. The article also considers Azerbaijan’s importance in the context of Russia–West confrontation.

О закате дугинского евразийства

Мнение, 03.06.2025

Эдуард Б. Атанесян

Аннотация

Статья посвящена контексту обращения российского философа Александра Дугина открытым письмом президенту Азербайджана Ильхаму Алиеву в мае 2025 года по поводу арестов «азербайджанских евразийцев», оцениваемых Дугиным как как удар по евразийской «Оси Москва–Баку». Рассматриваются идеологические основы концепции евразийства А. Дугина, ее отличия от классического евразийства и влияние ее постулатов на внешнюю политику России. Дается анализ геополитического значения Азербайджана как связующего с Центральной Азии звена в концепциях Х. Маккиндера, З. Бжезинского, а также в рамках понятийного аппарата самого А. Дугина. Рассматривается значение Азербайджана в контексте противостояния России и Запада.

Դուգինի եվրասիականության մայրամուտը

Կարծիք, 03.06.2025

Էդուարդ Բ. Աթանեսյան

Սեղմագիր

Հոդվածը նվիրված է 2025 թ. մայիսին ռուս փիլիսոփա Ալեքսանդր Դուգինի՝ Ադրբեջանի նախագահ Իլհամ Ալիևին հղված բաց նամակի համատեքստին՝ կապված «ադրբեջանցի եվրասիացիների» ձերբակալություններին, որոնք Դուգինի կողմից գնահատվում են որպես հարված եվրասիական «Մոսկվա–Բաքու առանցքին»։ Քննարկվում են Ա. Դուգինի եվրասիականության հայեցակարգի գաղափարական հիմքերը, դրա տարբերությունները դասական եվրասիականությունից և դրա բանաձևումների ազդեցությունը Ռուսաստանի արտաքին քաղաքականության վրա։ Տրվում է Ադրբեջանի աշխարհաքաղաքական նշանակության վերլուծությունը՝ որպես Կենտրոնական Ասիայի հետ կապող օղակ ըստ Հ. Մաքինդերի, Զ. Բժեզինսկու հայեցակարգերի, ինչպես նաև հենց Ա. Դուգինի հասկացութային ապարատի շրջանակներում։ Քննարկվում է Ադրբեջանի նշանակությունը Ռուսաստանի և Արևմուտքի հակամարտության համատեքստում։

Eduard B. Atanesyan

Background

In the second decade of May 2025, Russian philosopher and scholar Alexander Dugin, who is considered to be one of the prominent representatives of the Russian school of geopolitics, sent a letter to Azerbaijani President I. Aliyev regarding the arrests and harsh sentences of the few so-called “Azerbaijani Eurasians”, who had been detained in Azerbaijan in late 2024.

In his message, A. Dugin expresses sincere bewilderment and concern over the “severe punishment of the unfortunate people” who, from his perspective, merely “wanted the rapprochement between Russia and Azerbaijan” and promoted Eurasian ideas. He believes that these people acted sincerely and are innocent of the crimes they were accused of – espionage, treason, or incitement to violate Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity. The arrests and sentences were characterized by A. Dugin as a blow to the “Moscow–Baku Axis”(1), formed by Eurasians, and as an attempt to distance Azerbaijan from the Eurasian geopolitical project(2).

Speaking about the close and warm relations between Eurasians and the governmental, official, and intellectual circles of Azerbaijan, Dugin addresses a rhetorical query to the leader of Azerbaijan: “Do you really think that Baku simply managed to take back Karabakh? We put forward a project of a more peaceful and smooth transition, we defended it. But when the war began, who, in your opinion, stood behind the Azerbaijani scenario?”(3)

The history of the relationship between A. Dugin and the Azerbaijani side, which was marked by particularly warm ties, is not a recent phenomenon. For a considerable duration, maintained an amicable relationship with the well-known pro-Azerbaijani figure Heydar Jemal. This relationship was characterized by frequent visits to Azerbaijan with like-minded people. His visit in May 2017 was widely covered in the Azerbaijani media. Dugin visited Baku, met with representatives of the Russian community, visited the Cathedral of the Holy Myrrh Bearers, the Alley of shahids, and the grave of H. Aliyev. During the aforementioned visit, Dugin actively advocated for strengthening Russian-Azerbaijani relations, calling them “at the highest point” and emphasizing the importance of the “North–South” transport corridor.

According to certain accounts, he organized a trip to Baku for Russian writer Alexander Prokhanov in June 2017. One of the key results of the visit was an agreement to open a branch of the Izborsk Club in Baku, with the aim of facilitating closer communication between the intelligentsia and intellectuals of the Russian Federation and Azerbaijan. Subsequently, a delegation of the Club, including Alexander Dugin, visited Azerbaijan again. As part of this visit, or as its direct continuation, the conference “Moscow–Baku Axis: Towards a New Geopolitics of the Caucasus” took place. Following this conference, A. Prokhanov, as the head of the Izborsk Club, proposed holding the next conference “in Karabakh”. Dugin then emphasized: “Karabakh, from the point of view of the Russian Federation and the entire international law, is the territory of Azerbaijan”. He also visited Azerbaijan in the autumn of 2020, after the 44-day Artsakh War.

In accordance with the logic of his geopolitical views and the political preferences of the Russian foreign policy, he actively worked on the idea of keeping Baku in the mainstream of Russian foreign policy against the backdrop of Azerbaijan’s unequivocal drift towards NATO’s Ankara. In this regard, Eurasians were supposed to provide philosophical and intellectual support for the process of involving Baku in the Russian system of political coordinates, and, in particular, in the CSTO and the EAEU.

The Azerbaijani side, apparently, played along with the ideas and initiatives of Russian Eurasians for a time, monetizing the interest of Russian geopolitical theorists into fashionable opinions at the time, starting with “Russia should not fight for Armenia”, “that Armenians want to pit Russia and Turkey against each other”, and ending with the most radical calls to “put an end to the Armenian Project”. However, after achieving its goals, Baku not only generally lowered the quality of relations with Moscow but also took a number of emphatically anti-Russian steps, one of which, in particular, was the arrest of the “Azerbaijani Eurasians”. Covering Dugin’s letter, the Azerbaijani media touched upon his previous initiatives in, to put it mildly, an ironic way, implicitly, and no less ironically, by referring to Armenia as “Russia’s favorite outpost”(4).

As for the ideas voiced in the aforementioned letter by A. Dugin about Moscow’s direct support for the Azerbaijani scenario of capturing Nagorno-Karabakh, a number of reasonable questions arise here. But, before returning to them, let us first of all draw our attention to a thought that found its place in the letter to the head of Azerbaijan from the leading Russian geopolitician: “It seems to me that something in Azerbaijan is going completely wrong, as it should have gone”(5).

This passage can be seen as evidence that Alexander Dugin cannot accept political realities and does not understand why all this is happening. He lists the rules of the game with Azerbaijan that he adopted – warm relations with I. Aliyev and representatives of his administration, respect for H. Aliyev, etc., and at the same time is sincerely surprised that the Azerbaijani side behaves differently.

Given the author’s status, reportedly close to the highest Russian authorities(6), the very tone of his address to the head of Azerbaijan is a statement of the failure of the “second track diplomacy” in the context of Azerbaijani affairs. And if, in the case of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, failures and blunders on the foreign policy front are often inevitable elements of the functioning of all foreign policy offices dealing with dynamic processes and changing political situations, then in the case of the leading Russian geopolitician, it can be about the exposed ideological and methodological crisis of the Russian geopolitical thought, claiming influence on the policy of the Russian state. It turns out that one of the leading figures in the field of geopolitics and philosophy in Russia has long been communicating (including to the state structures) a certain understanding of the geopolitical picture and vectors of movement of the political subjects in our region, which subsequently turned out to be far from the real situation “on the ground”. Meanwhile, misunderstanding and ignoring the deep causes of the current situation “blinds” geopolitical thought and deprives it of the ability to model and predict processes.

For a more complete understanding of the dead end in which Dugin’s theoretical calculations found themselves, it is necessary to consider the political and ideological prerequisites of the situation that has formed around the “Dugin case”.

Russian Geopolitical Thought: From Eurasianism to Neo-Eurasianism

It is known that the Russian school of geopolitics, although it developed under the influence of Western theories (in particular, the ideas of Mackinder, Ratzel, and Mahan), has its unique features, determined by Russia’s historical experience, its geographical location, and civilizational originality. It can be considered a multi-vector phenomenon, including both pre-revolutionary ideas and post-Soviet thought, while during the Soviet era this science was considered a manifestation of bourgeois worldview, alien to the postulates of communism.

The central and most original concept of Russian geopolitical thought is the concept of “Russia–Eurasia”. The concept first emerged in the 1920s–1930s in the Russian emigration circles (P. N. Savitsky, N. S. Trubetskoy, L. P. Karsavin, and later L. N. Gumilev). They argue that Russia is neither Europe nor Asia, but rather an independent, unique cultural, historical, and geopolitical world, an “island”, a “continent” – Eurasia. Taking into account the unique geographical parameters of Russia, its intermediate position between Europe and Asia, Eurasians speak of a new identity because of the synergy and synthesis of Slavic, Turkic-Islamic, and Finno-Ugric elements in its culture. Thus, in cultural and spiritual terms, Eurasia for them is not just territory and room, but also a special environment with its own unique way of development.

From this vantage point, in general, come A. Dugin’s views, who is considered the author of Neo-Eurasianism. He developed the ideas of his predecessors and classics of geopolitics (Mackinder, Mahan, and Haushofer), making the concept of geopolitical dualism – the struggle of two civilizational types – “Land” (tellurocracy)(7) and “Sea” (thalassocracy)(8) a key aspect and principle for understanding global political processes in Eurasia and the entire world history. Advocating for the victory of “Land” over “Sea”, he speaks of the need to create a multipolar world consisting of several large civilizational blocs (Eurasian bloc led by Russia; European, Islamic, Chinese, etc.). His work “Foundations of Geopolitics”(9) calls for Russia to become the center of such a Eurasian bloc, opposing “Atlanticism”.

In general, A. Dugin’s geopolitical thought is a deeply ideological, anti-Western, anti-liberal, and anti-globalist doctrine, calling for a radical restructuring of the world order based on civilizational blocs under the leadership of continental powers, primarily Russia. Dugin assigns Russia the role of the “heart” of Eurasia (“Heartland”), and Moscow – “the natural strategic capital, the basis of the axes of any continental integration”(10), which must fulfill its historical mission of uniting continental powers and countries against the “Atlantic expansion”.

In practical terms, Dugin presents geopolitics as a full-fledged philosophy and ideology designed to influence the Russian state’s strategic decision-making. He brings it to a new political ideology – the “Fourth Political Theory” (“FPT”), which will go beyond the three main “classical” theories of the 20th century: liberalism, communism, and fascism. “FPT” should be based on geopolitical principles, traditionalism, the idea of multipolarity, and the values of “Land” (community, tradition, hierarchy, spirituality).

Classical Eurasianism vs. Neo-Eurasianism: A Comparative Analysis

Significant differences have emerged between the ideas of classical Eurasianism and Neo-Eurasianism, not least thanks to A. Dugin. Their analysis is important for determining the role of A. Dugin himself in the formation of geopolitical narratives, as well as for a clearer vision of the ideological and philosophical foundations of modern Russian foreign policy.

From the historical context, the classical Eurasianism, which emerged among Russian émigrés after the October Revolution of 1917, was an intellectual movement that sought to comprehend the Russian catastrophe(11) and find a unique, non-European path of development for Russia, considering its geographical position and cultural-historical synthesis. Neo-Eurasianism, in turn, appeared in the late 1980s and early 1990s in post-Soviet Russia as a response to the crisis of political identity(12) after the collapse of the USSR, the loss of geopolitical influence, and the desire to establish a new ideological basis for the revival of Russia as a major power in the conditions of the unipolar world existing at that time.

As a product of the intellectual circles of Russian emigration, the classical Eurasianism was rather a cultural, historiosophical, and geographical project, aimed at understanding the unique civilization of “Russia–Eurasia”, its differences from the West and East, and the search for its original path of development. It did not set goals and had no program of practical political steps. Meanwhile, Neo-Eurasianism is a geopolitical and ideological project closely linked to contemporary political realities. Its main goal is to substantiate the necessity of creating a multipolar world and forming a Eurasian bloc under the aegis of Russia to counter “Atlanticism” (the hegemony of the USA and Western liberalism). In this regard, it seeks to influence the strategy of its state.

Due to objective reasons, the classical Eurasianism was, by its very nature initially anti-Soviet, as it arose in exile and viewed Bolshevism as something alien to Russian civilization(13). Neo-Eurasianism, in turn, is significantly more positive towards the Soviet period, viewing it as a continuation of imperial statehood and a form of “Eurasian unity” capable of opposing the West.

While advocating for Russia’s uniqueness, classical Eurasianism was relatively moderate in its political conclusions, whereas Neo-Eurasianism is more radical and eclectic. It synthesizes ideas of classical Eurasianism with elements of traditionalism (it is against modernity and is for traditional values), “Conservative Revolution”, certain aspects of fascism(14), and classical geopolitical theories of Mackinder, Haushofer, Schmitt (with a more severe interpretation of the confrontation between “Land” and “Sea”).

From a religious point of view, in classical Eurasianism Orthodoxy played a key, though not the only, role, in the formation of the Eurasian civilization. While in Neo-Eurasianism, Orthodoxy remains an important element, but special emphasis is placed on interfaith dialogue and the inclusion of other traditional religions (especially Islam) into a single Eurasian bloc as forces opposing the Western secularism.

In terms of practical orientation, classical Eurasianism remained, mainly, in the sphere of intellectual and philosophical reflection, without the goal of seizing power or implementing specific state projects. Neo-Eurasianism, however, actively seeks to influence the state policy in Russia, proposes appropriate foreign policy strategies, integration projects (for example, the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) as an embodiment of the “Eurasian idea”) , and is involved in forming of the corresponding ideological base for both elites and society at large. Thus, Neo-Eurasianism can be viewed as a radicalized, politicized, and synthetic version of classical Eurasianism, adapted to the realities of the post-Soviet world with an emphasis on geopolitical confrontation with the collective West and the justification of Russia’s special mission.

From “Third Rome” to Eurasianism: A Paradigm Shift

Even without a meticulous account of Dugin’s concepts, Eurasianism, as a geopolitical idea that today claims to define priorities and form the basis of Russia’s state policy, already represents a fundamental departure from the earlier and more popular political-ideological concept of “Moscow–Third Rome” (conditionally – “M3R”), which emerged in the 15th-16th centuries. According to it, after the fall of the first Rome (due to “the Latin heresy”) and the “second Rome” (the capture of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks), Moscow (and the Russian Tsardom) emerged as the sole custodian of “true Orthodoxy” and a protector of the Christian peoples.

The radical, in essence, change in the philosophical and ideological paradigm of the development of the Russian people and state affects a number of key parameters.

First of all, we note the change in the concept of identity: in the case of “M3R”, identity is based on the religious (Orthodox) exclusivity and spiritual mission, where Russia is the guardian of the “true faith”, while Eurasianism offers a different formula for identity: geographical uniqueness, cultural synthesis (Slavic, Orthodox, and Turkic-Muslim), as well as a special geopolitical position between East and West(15). Religion (Orthodoxy, Islam) is considered as one of, but not the only or dominant, element.

There are also significant differences in approaches to the “Turanian” (Turkic-Mongolian) heritage. Due to historical reasons, “M3R” traditionally views the “Turanian” heritage in a negative light, perceiving it as a period of “yoke” and humiliation from which Russia freed itself by force(16). Eurasianism, on the other hand, sees the Mongol-Tatar influence as a key factor in the formation of the centralized Russian state, a special administrative culture, and the geopolitical unity of the Eurasian regions. Some Eurasians even considered the Golden Horde as a “proto-Eurasian state”(17).

Differences also exist in the sphere of practical application: the “M3R” concept is universalistic in nature, and in a religious sense, Russia is seen as the guardian of universal truth that must be disseminated, while Eurasianism focuses on the particularity (uniqueness, originality) of the Eurasian civilization, which is not universal, not applicable to all, and must preserve its uniqueness(18).

The concepts have different visions of what is commonly called “the East”: “M3R” views the Islamic world as an external threat or an object of missionary activity, while Eurasianism perceives the East (particularly Central Asian, Turkic, and Finno-Ugric peoples) as an organic part of the Russian civilization, its “second self”, with which symbiosis and cooperation are necessary.

In terms of geopolitical priorities, the following picture emerges: the imperial ambitions of the “M3R” concept stem from a religious mission – the protection of Orthodox and, more broadly, oppressed Christian peoples(19), meanwhile Eurasianism articulates the geopolitical struggle of “Land” (Eurasia) against “Sea” (Atlanticism), with an emphasis on the strategic integration of continental spaces and the creation of a multipolar world.

In essence, neo-Eurasianism indirectly contributed to excluding the Russian state’s return to notions of Russia’s sacred and universalist role as a world power in human civilization.

The particularism of the chosen path places Moscow on par with other global actors and regional competitors, inherently depriving it of unique advantages even on its own territory(20). For example, in terms of “Islamic heritage”, Moscow finds it difficult to counter recognized centers of the Islamic (both Sunni and Shiite) world; it unequivocally loses to Turkey in terms of being a symbol and locomotive of the “Turkic identity” (even despite the anti-Western essence of “Turkish Eurasianism” itself); Chinese economic expansion in the Far East of RF forms a new reality of political and economic dualism, where regions, while being part of the Russian Federation, are increasingly integrated with Beijing; the Russian model of multiculturalism and common history, built on the primacy of “common victory in WWII”, avoids the sharp corners of “post-war” and “post-Soviet” realities that defy analysis from the perspective of a common Soviet unity in the fight against German fascism, etc..

The purpose of this extensive digression was to demonstrate various aspects of the palette of the geopolitical concepts and ideas associated with the long-standing activity of A. Dugin as a leading Russian philosopher and geopolitician. Bearing in mind his idea of the enduring conflict between tellurocracy and thalassocracy and Russia’s key role in it, let us return to the author’s above-mentioned idea that “Baku could not have taken Karabakh on its own” (implying – without Russian assistance), and the question “When the war began, who, in your opinion, stood behind the Azerbaijani scenario?”.

The author’s adherence to the Azerbaijani paradigm concerning the Karabakh problem is evident and unquestionable. This is his right, his position as a person with his own sympathies, and possibly – antipathies. The question is not even, whether his point of view reflects the realities and official position of the Russian state, because A. Dugin, formally, does not hold state positions and, ideally, is free to express any point of view. For us, the question lies in the plane of the practical consonance of the author’s political views with his own theoretical geopolitical postulates.

Central Asia in the Focus of Western Geopolitics

The initial focus will be on Central Asia, which Halford Mackinder – the author of “Heartland” or “The Geographical Pivot of History”, and following him, Karl Haushofer, considered part of the Eurasian Heartland. The British geographer and one of the founders of geopolitics, H. Mackinder, attached exceptional importance to it in his famous concept. For him, Central Asia is the very heart of the Heartland(21). In his article “The Geographical Pivot of History” (1904) and subsequent works, especially “Democratic Ideals and Reality” (1919), he singled out a vast area of Eurasia, largely inaccessible to maritime powers, as the “Heartland”. The author noted several reasons for its importance, of which the most relevant today is the role of Central Asia as a buffer between various civilizations (Russian, Chinese, Indian), possessing significant opportunities for creating communication and being, in this context, a convenient springboard for (in H.M.’s time – for Russian expansion) domination over the coastal zones of Eurasia. Mackinder’s goal was to warn the British government about the potential threat posed by any land power that could unite the resources of the Heartland (including Central Asia), which should not be given into the hands of one dominant power. His approach was focused on deterring and preventing the emergence of a leading continental power capable of threatening Britain’s maritime supremacy(22).

In the relatively recent past, Zbigniew Brzezinski, an American political scientist and statesman, former U.S. President’s National Security Advisor, also distinguished himself by his special attitude towards Central Asia. He devoted particular attention to this concept in his geopolitical concepts, and, in particular, in his most famous work “The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives” (1997).

For Brzezinski, as for Mackinder, Central Asia represents a strategically vital region of Eurasia, playing a decisive role in maintaining American dominance and deterring the emergence of a Eurasian hegemon. This region is a key element of the “Grand Chessboard” where the fate of global leadership was decided. In his opinion, being at the very heart of Eurasia, at the crossroads of interests of major powers such as Russia, China, Iran, Turkey, and the West, the region was crucial for controlling Eurasia, and, consequently, the world. His approach involved active U.S. involvement in the region to maintain its fragmentation, ensure access to resources, and prevent the dominance of any one competing great power. Being convinced of the high geopolitical instability of the region, its ethnic and religious heterogeneity, porous borders, and proneness to conflicts, Z. Brzezinski introduced the term “Eurasian Balkans” (including in it the South Caucasus and Afghanistan) to designate the Central Asian region. At the same time, he knew that the region possesses significant oil and gas reserves, which makes it strategically important for global energy security. Z. Brzezinski emphasized the imperative to ensure access to these resources and diversify their transportation routes, in order to avert a Russian monopoly.

Central Asia has not lost its significance as a buffer zone between Russian, Chinese, and Indian civilizations, as well as a raw material and communication resource, even today – against the backdrop of the dismantling of the U.S. political and economic hegemony and the transition to a multipolar world architecture. Modern geopolitical trends lead to increased competition between the main geopolitical actors, including on new platforms that emerged after the collapse of the USSR. In this regard, the “Sea powers” – the USA, and Britain, have long been working on creating and expanding political and economic ties with the region.

“ARVAK” has already published materials on modern transport and communication projects and initiatives that are aimed at optimizing multimodal transit of goods and raw materials, as well as stimulating economic integration and expanding trade ties of the region in the system of global trade and transport relations along the West (EU)–East (China, India) axis. Consequently, the formation of these ties “bypassing Russia” became one of the key geopolitical and economic priorities, especially after 2014 (“Crimean events”) and sharply intensified after 2022 (the start of Russia’s Special Military Operation in Ukraine).

The efforts initiated by the “Sea powers”, aimed at reducing dependence on Russia as a transit route, increasing energy security, diversifying supply chains, and developing regional integration, had unambiguously political goals, as did, in fact, a number of “integration projects” of a political nature – they are being implemented in full accordance with the postulates of Mackinder and Brzezinski. And among them, first of all, we are talking about the “Turanian project”, consistently implemented through “Organization of Turkic States” (OTS), known as “Turkic Council” until November 2021. The OTS was created to develop cooperation between independent Turkic states(23) in areas such as economy, culture, education, transport, tourism, etc. Although the OTS positions itself as a platform for peaceful and pragmatic cooperation, and not as an instrument of territorial expansion, nevertheless, within the OTS and among its members, there is a steady increase in cooperation in the field of defense and security. The closest ties in the military sphere already exist between Turkey and Azerbaijan (for example, the “Shusha Declaration”, providing for mutual military assistance), Ankara is also developing military cooperation with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan(24), including arms supplies (for example, Bayraktar drones), military training, and joint drills. Under the auspices of Turkey within the OTS, discussions are underway on combating “international terrorism, separatism, and extremism”. Countries exchange experience and hold consultations on regional security and the military-industrial complex. Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan has repeatedly called on the countries of the Turkic world to strengthen cooperation in the military and defense sphere(25).

Apparently, the importance of Central Asia as a “vitally important component of the future Eurasian Union” is recognized by Dugin himself, who envisions the creation of the latter under the aegis of Russia. In his opinion, this union is conceived as a powerful continental bloc capable of opposing the hegemony of the United States and Western liberalism (Atlanticism). He emphasizes the need to integrate Central Asian countries into the Russian system of political, economic, and military coordinates, seeing this as a guarantee of their own stability and sovereignty. In addition, he actively criticizes any external (especially – American and European) influence in Central Asia, viewing it as an attempt by the “Atlanticists” to encircle and weaken Russia, to tear Central Asia away from its “natural” Eurasian center(26). It is in this context that he considers Turkey as a “strategic element of Atlanticism”, and the “Turanian project” as a “very dangerous version of anti-Russian pseudo-Eurasianism”(27). “…The Turkish influence poses a huge danger for the CIS and Russia – as a carrier of a destructive geopolitical impulse”, he believes(28). At the same time, the “color revolutions”, in his view, are the promotion of Western democratic values in the region, as they are aimed at destabilizing and drawing countries into the orbit of the “Sea Civilization”.

The Value of Azerbaijan in Western Geopolitical Projects

And now, taking into account the geopolitical significance of the Central Asian region in facilitating connection and interaction between the three emerging Eurasian continental poles (Russian Federation, China, and India), it is imperative to redirect our attention to Azerbaijan.

At one time, Brzezinski emphasized the importance of Azerbaijan as one of the “Pivotal States” deserving the strongest geopolitical support from the United States. The country’s strategic importance, as evidenced by its prominent placement on the “Grand Chessboard”, is primarily attributed to its geographical location in the Caucasus region, which provides access to the Caspian Sea. That is why the process of “cracking” of Russia’s “soft underbelly” began with this South Caucasian republic. At one time, the so-called “Contract of the Century” – a large-scale oil agreement signed in 1994 between Baku and an international consortium of oil companies, led by British Petroleum, opened up West’s access (“thalassocracy”) to the development of the largest oil fields in the Caspian region (“Azeri”, “Chirag,” and “Gunashli”).

The contract became revolutionary in terms of its conditions and scale, managing to attract significant foreign investments into the post-Soviet country. This, in turn, contributed to infrastructure development, and marked the onset of a new stage in the region’s oil industry. The project had a significant impact on Azerbaijan’s economic development, and pipeline projects bypassing Russia (e. g., Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan) led to a radical decrease in Russian influence in the region – in full accordance with the vision of Z. Brzezinski and H. Mackinder. The “ARVAK” Center has already touched upon the importance of the Azerbaijani track of the collective West’s policy in the South Caucasus region, viewing it as the direction of the main “attack” in the confrontation with Russia(29).

If we consider the geopolitical processes initiated by the West with the involvement of Azerbaijani territory to access Central Asia in terms of Dugin’s own glossary(30), then we can speak of integration(31), or rather – “latitudinal integration” (integration along parallels), which Dugin considers the most vulnerable and difficult moment in linking geopolitical spaces controlled by a center. Latitudinal integration is defined as the gradual joining of heterogeneous regions to the central part through a spatial hierarchy of sectors most loyal to the center by peaceful and diplomatic means. We are witnesses to this loyalty of Baku to the West through participation in various integration projects. In turn, the “latitudinal expansion” (expansion along parallels) represents an offensive geopolitical strategy that generates conflict situations and military conflicts. An example of this can be considered Azerbaijan’s strategy of pushing through the so-called extraterritorial “Zangezur Corridor”, something that is loyally perceived by non-regional poles of power.

There is a temptation to explain such a “pardoning” attitude of official Western circles towards authoritarian Azerbaijan within the logic of geoeconomics – an offshoot of Atlanticist geopolitics that views space, in this case, Azerbaijan, in a purely utilitarian-economic light. Without denying the economic significance of this territory within the broader context of American and European policy, it is crucial to emphasize a pivotal aspect from the point of view of political geography that allows a comprehensive understanding of Azerbaijan’s role within the idea of the overall Euro-Atlantic world order.

So, if the Eurasian continent is “cut” at its “thinnest” (from the perspective of its political structure) point, an imaginary line from the Arctic Ocean to the Indian Ocean would pass through only three countries – Russia, Azerbaijan, and Iran. Given the ongoing geopolitical confrontation between the West and Russia and Iran, Azerbaijan, in essence, functions as the only “viable” corridor (and simultaneously a “bottleneck”) for the entire geopolitical construction of the West, built strictly along the West–East axis, into the heart of Eurasia. If we follow the “law of spatial progression” formulated by Jean Thiriart, the geographical dynamics of political history relentlessly led to an increase in the scale of minimal social formations according to the principle of “from city-states through territorial states to continental states”. In this case, it turns out that the inevitable process, this time of the “meridional integration” (integration along the North–South axis), should (or should have) affected the territory of Azerbaijan within the framework of Russian-Iranian integration processes and is carried out in a soft but persistent mode. The “stalling” of soft policy, ideally, should have initiated the so-called “meridional expansion” (expansion along the North–South axis) – with the expansion of the sphere of Russian and Iranian influence (military, strategic, cultural, or economic) along the meridian.

Historically, this territory has alternated between Iranian and Russian ownership, with the exception of 2 brief periods (first – from 1918 to 1920 and second – from 1991 to the present day) of 36 years in total. This circumstance has affected the political, economic, religious, and other aspects of life in Azerbaijan. Thus, in historical, religious, and cultural terms (traditional architecture, poetry, music, etc.), the population of this territory has traditionally identified itself as an integral part of the Iranian civilization, its periphery, subsequently conquered by Russian Tsarism(32). In turn, Azerbaijan’s presence within the Russian, and then Soviet, powers led to economic development, the creation of infrastructure, the development of science and technology, the emergence of an education system, the formation of a national elite, etc. The Russian language maintains its significance in contemporary Russia as one of the key languages for technical education and professional communication.

These factors naturally support corresponding trends in the Azerbaijani environment that can be exploited by the northern and southern neighbors within the framework of “integrative processes” along the “North–South” line. Therefore, they are subject to the reformatting of Azerbaijani society within a new political-ideological paradigm that defines the role and place of Azerbaijan in the region’s new architecture – a common Turkic identity. This includes a smooth transition to Sunnism, anti-Russian narratives (which have intensified recently), Iranophobia, and political-economic integration processes within the framework of latitudinal integration “West–East”, openness to the collective West. However, Azerbaijan will remain “invincible” on the way of the Russian-Iranian rapprochement.

Azerbaijan’s value to the collective West is determined by its ability to a) cut Russia off from Iran (or vice versa) and b) prevent the simultaneous geopolitical blocking of Western access to Central Asia (the heart of Mackinder’s Heartland) with the aim of subsequent control over Eurasia. This will continue as long as Baku plays by Western rules, so the appeals to “the respect for Heydar Aliyevich” are absolutely powerless here.

While opposing Pan-Turanism and calling it an opponent of the “true Eurasianism”, A. Dugin refuses to see the strategic role assigned to Baku in it, considering the space of former Soviet Central Asia as the zone of close Russian-Iranian cooperation, whereas the more logical place is Azerbaijan. In his understanding, it is about “Pax Persica”(33) – a certain project to reorganize the geopolitical landscape of Central Asian under the aegis of Iran in alliance with Russia, while these two states are separated by a significant strip of land in that part of the continent. The result of Russia’s geopolitical waltz with Iran was that some in the Iranian establishment have begun looking for ways to improve relations with the United States(34).

Meanwhile, due to the historical conditions of its creation and its strategic function in the region, Azerbaijan clearly falls under A. Dugin’s own definition, as provided in the Glossary of his famous work: “Sanitary cordon – artificial geopolitical formations serving to destabilize two large neighboring states capable of forming a serious bloc, which, in turn, would be dangerous for a third party. A classic move in the Atlanticists’ strategy in their confrontation with continental integration of Eurasia”(35). And yet he himself and his like-minded people actively worked to strengthen this “classic move of the Atlanticists in their confrontation with continental integration of Eurasia” until recently.

It is a known fact that the existence of Artsakh statehood in its historical territories did not hinder the development of regional transport and energy projects in any way. At the same time, its presence in its historical area, due to natural geographical reasons, almost halved the width of the “Azerbaijani transport and energy corridor”, through which the appropriate communications passed to Georgia and further to the west. As a result, a unique geopolitical situation existed in the region: a balance of interests of global actors that prevented destabilization of the situation, maintaining relative peace and stability by the parties themselves, a balance of forces and capabilities of the parties, and the possibility of peaceful coexistence under conditions of mutual deterrence. From a geopolitical perspective, the dismantling of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic and the expansion of the “Azerbaijani corridor” initiated by the West were precisely the focus of the long-term efforts of Eurasianist A. Dugin, and, as can be seen, others.

Instead of a Conclusion

It has been posited that Alexander Dugin’s letter addressed to Ilham Aliyev was also intended for other high-ranking addressees – those whom the author once convinced of the reality and feasibility of the “Moscow–Baku Axis”. But practical, applied geopolitics demonstrated that this is not the case, and that the prominent Russian geopolitician was mistaken in his theoretical calculations, unless, of course, everything was planned exactly this way.

And in general, there is nothing unusual, or even cruel, in Azerbaijan’s attitude towards Alexander Dugin and his “Moscow–Baku Axis”: at one time, by order of Mustafa Kemal, 15 leaders and activists of the Communist Party of Turkey (CPT) were arrested and assassinated on a small vessel on the night of January 28-29, 1921, and their bodies were dumped into the Black Sea off the coast of Trabzon. This was a direct and clear message from Kemal to the Bolsheviks, who had gotten carried away with allied games with their Turkish “comrades”. Azerbaijan, apparently, this time chose not to use the traditional “method” of clear demonstration of its attitude towards Moscow.

In conclusion, let us recall another term from the glossary of A. Dugin’s book: “Friend (amicus Lat.) – Schmitt’s term. A purely political concept. Denoting a set of external state, social, ethnic, or religious formations that stand on positions coinciding with the positions of the strategic capital. It has no moral connotation and can be dynamically transferred to various formations. A movable category”.

SOURCES AND LITERATURE

- Margaryan R., “Dugin writes to Aliyev”. Russia-Armenia.info // “Center for Support of Russian-Armenian Strategic and Public Initiatives”, 27.05.2025, https://russia-armenia.info/ node/103649

- Dugin: Do you think Baku easily managed to take Karabakh? “Voice of Armenia”, 23.05.2025, https://www.golosarmenii.am/article/237409/dugin-dumaete-baku-tak-prosto-udalos-vzyat-karabax

- Ruzanna Harutyunyan, “Dear Ilham Heydarovich! I hope this is just a misunderstanding, and everything will be resolved soon”: Alexander Dugin. 24.05.2025, https://hraparak.am/post/0b4bcf8245c80453adae00f4b97ba416?ysclid=mb7kjcohzd955658 726

- When Azerbaijan does not want to join the Russian world, Dugin has a fit. minval.az, 23.05.2025, https://icma.az/ru/news/kogda-azerbajdzhan-ne-hochet-v-russkij-mir-u-dugina-nachinaetsya-pripadok-760807?ysclid=mb7kjo3wvh974291503

- Dugin A. G., Foundations of Geopolitics, M.: Arktogeya, 1997, https://virmk.ru/read/d/DUGIN/content.htm (in Rus.), https://archive.org/details/foundations-of-geopolitics-geopolitical-future-of-russia-alexander-dugin-english/mode/2up (in Eng.).

- Berdyaev N. A., Eurasianism, Book Four, “Eurasian Herald”. Berlin, 1925, http://royallib.ru/book/berdyaevnikolay/evraziytsi.html

- Anton Shekhovtsov, “Russia and the Western Far Right: Eurasianism, Geopolitics and the Appeal of an Idea” (2017) https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/97813155609 91/russia-western-far-right-anton-shekhovtsov; Anton Shekhovtsov, “Aleksandr Dugin’s Neo-Eurasianism: The New Right à la Russe” (2009) https://www.academia.edu/197900/Aleksandr Dugins_Neo_Eurasianism_The_New_Right_%C3%A0_la_Russe; Marlene Laruelle, “Russian Nationalism: Imaginaries, Doctrines, and Political Battlefields”, https://www.academia.edu/44294487/Marlene_Laruelle_2018_Russian_Nationalism_Imaginaries_Doctrines_and_Political_Battlefields_London_Routledge; Michael Millerman, “Alexander Dugin – The Ideologue of Russian Fascism and Imperialism”, https://insightnews.media/alexander-dugin-the-ideologue-of-russian-fascism-and-imperialism/; Andreas Umland: “Andreas Umland: Fascist Tendencies in Russia’s Political Establishment… The Rise of the International Eurasian Movement”. https://www.historynewsnetwork.org/article/andreas-umland-fascist-tendencies-in-russias-polit; Charles Clover, “Black Wind, White Snow: The Rise of Russia’s New Nationalism”, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308371935_Black_Wind_White_Snow_The_Rise_of_Russia’s_New_Nationalism.

- Philosopher Dugin: “Historical destiny shows us the way to the East”, BUSINESS Online, 08.10.2019, https://www.business-gazeta.ru/article/441685

- Alexander Dugin: “Pan-Turanism claims Crimea, the Caucasus and other ethnic groups of the Caucasus – for example, Avars and Lezgins.” 24.05.2012, https://flnka.ru/digest-analytics/577-aleksandr-dugin-panturanizm-pretenduet-na-krym-na-kavkaz-i-na-drugie-etnosy-kavkaza-naprimer-na-avarcev-i-lezgin.html

- “Information about Uzbekistan’s accession to the Shusha Declaration refuted / The Uzbek Foreign Ministry stated that the country is not a party to the declaration on alliance and joint defense signed by Turkey and Azerbaijan.” 24.05.2025, https://kun.uz/ru/news/2025/05/ 24/informatsiya-o-prisoyedinenii-uzbekistana-k-shushinskoy-deklaratsii-oprovergnuta

- “Hakan Fidan on the Turkic world: ‘Let’s unite, become stronger…’” / Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan has repeatedly called on the countries of the Turkic world to strengthen cooperation in the military and defense sphere”. TRT Russian, 19.09.2024, https://www.trtrussian.com/novosti-turciya/hakan-fidan-o-tyurkskom-mire-davajte-splotimsya-stanem-silnee-18210215

- “Russia traditionally views Central Asia, predominantly inhabited by Islamic peoples, as a zone of its historical responsibility.” Alexander Dugin, Geoполитика.ru, 04.10.2019, https://www.geopolitica.ru/article/povorot-k-vostoku-zametki-o-evraziystve-i-valdayskom-klube

- Simavoryan A., Comparative analysis of the ideologies of “Turkish Eurasianism” and “Russian Eurasianism”. ARVAK Analytical Center, 10.07.2023, https://bit.ly/453vD3U

- Astvatsatur Ter-Tovmasyan, Main and distracting blows in the confrontation between the West and Russia. 13.03.2024, ARVAK Analytical Center, https://bit.ly/4dTZZZ1

(1) Margaryan R., Dugin writes to Aliev. (in Rus), Russia-Armenia.info / Center for Support of Russian-Armenian Strategic and Public Initiatives, 27.05.2025, https://russiaarmenia.info/node/103649 (download date: 03.06.2025).

(2) Dugin: Do you think Baku managed to take Karabakh so easily? (in Rus.), “Golos Armenii”, 23.05.2025, https://www.golosarmenii.am/article/237409/dugin-dumaete-baku-tak-prosto-udalos-vzyat-karabax (download date: 03.06.2025).

(3) Ruzanna Harutyunyan, “Dear Ilham Heydarovich! I hope this is just a misunderstanding and everything will be resolved soon”: Alexander Dugin. (in Rus.), Hraparak.am, 24.05.2025, https://hraparak.am/post/ 0b4bcf8245c80453 adae00f4b97ba416?ysclid=mb7kjcohzd955658726 (download date: 03.06.2025).

(4) When Azerbaijan does not want to join the Russian world, Dugin starts having a fit. (in Rus.), minval.az, 23.05.2025, https://icma.az/ru/news/kogda-azerbajdzhan-ne-hochet-v-russkij-mir-u-dugina-nachinaetsya-pripadok -760807?ysclid=mb7kjo3wvh974291503 (download date: 03.06.2025).

(5) Arutyunyan R., “Dear Ilham Heydarovich! Hope, it’s just a misunderstanding and everything will be resolved soon”: Alexander Dugin. (in Rus.), Hraparak.am, 24.05.2025, https://hraparak.am/post/0b4bcf 8245c80453adae00f4 b97ba416?sclid=mb7kjcohzd955658726 (download date: 03.06.2025).

(6) Thus, according to some information, his book “Foundations of Geopolitics” (1997) was used as a textbook in the Academy of the General Staff of the Russian Federation and other law enforcement agencies. It is also known that many of his concepts – “multipolar world”, “confrontation with ‘Atlanticism’”, criticism of the “liberal West”, the idea of a “special civilizational mission of Russia” – often coincide with official rhetoric of RF, especially – in recent years.

(7) Tellurocracy (Greek) – “power through land” or “land power” – characteristics of powers with a clear land-based geopolitical orientation.

(8) Thalassocracy (Greek) – “power through the sea” or “sea power” – characteristics of states and nations with a predominance of seafaring.

(9) Dugin A. G., Osnovi Geopolitiki (Foundations of Geopolitics) (in Rus.), Moscow: Arktogeya, 1997, https://virmk.ru/read/d/DUGIN/content.htm (download date: 03.06.2025); https://archive.org/details/foundations-of-geopolitics-geopolitical-future-of-russia-alexander-dugin-english/mode/2up (in Eng.) (download date: 03.06.2025).

(10) Ibid, Glossary, https://virmk.ru/read/d/DUGIN/chapt09.htm (download date: 03.06.2025).

(11) According to N. A. Berdyaev: “Eurasianism is, first of all, an emotional rather than an intellectual trend, and its emotionality is a reaction of creative national and religious instincts to the catastrophe that has occurred. This kind of spiritual formation can turn into Russian fascism”. See: Berdyaev N. A., Eurasianism, Book Four (in Rus.), “Eurasian Herald”, Berlin, 1925. http://royallib.ru/book/berdyaevnikolay/evraziytsi.html (download date: 03.06.2025).

(12) “Who are we, Russians, Slavs or Rossians (Rossiyane, i.e. the citizens of Russia)?”

(13) Some “left Eurasians” (L. P. Karsavin, P. P. Suvchinsky, D. P. Svyatopolk-Mirsky, N. V. Ustrialov) later tried to find common grounds with the Soviet government, seeing in the USSR a new form of imperial integrity of Russia, which, however, did not prevent the Soviet government from repressing those of them who risked returning to their homeland in the mid-1920s.

(14) A. Dugin formally rejects “fascism” as a Western phenomenon, but some critics find parallels in his authoritarian and anti-liberal views. See: Anton Shekhovtsov, “Russia and the Western Far Right: Eurasianism, Geopolitics and the Appeal of an Idea” (2017), https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/97813155609 91/russia-western-far-right-anton-shekhovtsov; Anton Shekhovtsov, “Aleksandr Dugin’s Neo-Eurasianism: The New Right à la Russe” (2009), https://www.academia.edu/197900/Aleksandr_Dugins_ Neo_EurasianismThe_ New_Right_%C3%A0 _la_ Russe; Marlene Laruelle, “Russian Nationalism: Imaginaries, Doctrines, and Political Battlefields”, https://www.academia.edu/44294487/Marlene_Laruelle_2018_RussianNationalism_Imaginaries_Doctrines_and_Political_Battlefields_London_Routledge; Michael Millerman, “Alexander Dugin – The Ideologue of Russian Fascism and Imperialism”, https://insightnews.media/alexander-dugin-the-ideologue-of-russian-fascism-and -imperialism/; Andreas Umland: “Andreas Umland: Fascist Tendencies in Russia’s Political Establishment… The Rise of the International Eurasian Movement”. https://www.historynews network.org/article/andreas-umland-fascist-tendencies-in-russias-polit; Charles Clover, “Black Wind, White Snow: The Rise of Russia’s New Nationalism” (2016), https://www.researchgate.net/publi cation/308371935_Black_Wind_White_Snow_The_Rise_of_Russia’s_ New_Nationalism (03.06.2025).

(15) N. A. Berdyaev claimed that: “The Eurasians want to remain nationalists, closed off from Europe and hostile to Europe. In this way they deny the universal significance of Orthodoxy and the world, calling Russia as a great world of East-West, uniting the two streams of world history”. See: Berdyaev N. A., Eurasianism, Book Four, Eurasian Herald, Berlin, 1925, http://royallib.ru/book/berdyaevnikolay/evraziytsi.html (download date: 03.06.2025).

(16) A reference to the theme is noticeable in the very first lines of a famous song from 1941, “The Sacred War” (words by V. Lebedev-Kumach, music by A. Alexandrov), which became the anthem of the struggle against the fascist aggression during the Great Patriotic War: “Rise up, huge country, rise up for mortal combat, with the dark fascist force, with the damned horde”.

(17) For example, N. S. Trubetskoy, P. N. Savitsky, G. V. Vernadsky.

(18) Thus, Dugin notes with pleasure that V. Putin, during the meeting of the Valdai Club in October 2019, spoke, in essence, within the framework of the Eurasian idea: “Russia is a country-civilization that has organically absorbed many traditions and cultures, preserved their originality, uniqueness and, at the same time, preserved, which is very important, the unity of the peoples living in it. We are very proud of this harmony of originality and common destiny of the peoples of Russia, and we value it very much”. See: Philosopher Dugin: “Historical fate shows us the way to the East”. BUSINESS Online, 08.10.2019, https://www.business-gazeta.ru/article/441685 (download date: 03.06.2025).

(19) The Russian state is thus abandoning the political and ideological foundations of the status of the “defender of the Christian peoples”, which at one time served as an understandable and perceptible justification for Russia’s Balkan, Eastern European, and Caucasian policies. Protection of the Christian peoples was the legitimate ideological basis for the “meridional expansion” and then the “integration” policies of the Russian state in the Caucasus and its confrontation with the Ottoman and Persian powers.

(20) Alexander Dugin: “Panturanism claims the Crimea, the Caucasus and other ethnic groups of the Caucasus – for example, the Avars and Lezgins”. (in Rus.), 24.05.2012, https://flnka.ru/digest-analytics/577-aleksandr-dugin-panturanizm-pretenduet-na-krym-na-kavkaz-i-na-drugie-etnosy-kavkaza-naprimer-na-avarcev-i-lezgin.html (download date: 03.06.2025).

(21) According to Mackinder: “Who controls Eastern Europe commands the Heartland. Who controls the Heartland commands the “World Island” (Eurasia + Africa). Who controls the “World Island” commands the world”.

(22) Mackinder’s assessments of Central Asia were shared and developed by another classic geopolitician, the German Karl Haushofer, who tried to adapt them to Germany’s geopolitical interests. He, too, in particular, emphasized the importance of developing transport infrastructure (railways) in Central Asia to strengthen the integration of the Heartland and the effective use of its resources.

(23) The organization includes Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. Hungary, Turkmenistan, and the so-called “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” have observer status.

(24) Despite circulating rumors, Uzbekistan rejects joining the “Shushi Declaration”. See: “Information on Uzbekistan’s accession to the Shushi Declaration has been refuted // The Uzbek Foreign Ministry stated that the country is not a party to the declaration on alliance and joint defense signed by Turkey and Azerbaijan (in Rus.), 24.05.2025, https://kun.uz/ru/news/2025/05/24/informatsiya-o-prisoyedinenii-uzbekistana-k-shushinskoy-deklaratsii-oprovergnuta (download date: 03.06.2025).

(25) See: “Hakan Fidan on the Turkic world: “Let’s unite, let’s become stronger…” / Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan has repeatedly called on the countries of the Turkic world to strengthen cooperation in the military-defense sphere”. TRT Russian (in Rus.), 19.09.2024, https://www.trtrussian.com/novosti-turciya/hakan-fidan-o-tyurkskom -mire-davajte-splotimsya-stanem-silnee-18210215 (download date: 03.06.2025).

(26) «Russia has traditionally viewed Central Asia, populated predominantly by Islamic peoples, as an area of its historical responsibility». Aleksandr Dugin, Geopolitika.ru (in Rus.), 04.10.2019, https://www.geopolitica.ru/article/povorot-k-vostoku-zametki-o-evraziystve-i-valdayskom-klube (download date: 03.06.2025).

(27) Alexander Dugin: “Panturanism” claims the Crimea, the Caucasus and other ethnic groups of the Caucasus – for example, the Avars and Lezgins. (in Rus.), 24.05.2012, https://flnka.ru/digest-analytics/577-aleksandr-dugin-panturanizm-pretenduet-na-krym-na-kavkaz-i-na-drugie-etnosy-kavkaza-naprimer-na-avarcev-i-lezgin.html. See also: Simavoryan A., Comparative Analysis of the Ideologies of “Turkish Eurasianism” and “Russian Eurasianism”. ARVAK Analytical Center, 10.07.2023, https://bit.ly/453vD3U (download date: 03.06.2025).

(28) Alexander Dugin: “Panturanism” lays claim to Crimea…”

(29) Astvatsatur Ter-Tovmasyan, The Main and Distracting Blows in the Confrontation between the West and Russia. March 13, 2024, Expert Commentary, ARVAK Analytical Center, https://bit.ly/4dTZZZ1 (download date: 03.06.2025).

(30) Dugin A., Foundations of Geopolitics…

(31) Integration – in geopolitics means various forms of unification of several spatial sectors. Integration can be carried out both on the basis of military expansion and peacefully. There are several paths of geopolitical integration – economic, cultural, linguistic, strategic, political, religious, etc. All of them can lead to the same result – an increase in strategic and spatial volume.

(32) The Gulistan and Turkmenchay treaties, according to which, allegedly, Azerbaijan was divided into “Northern” and “Southern”, do not contain any mention of the word “Azerbaijan” at all. Speaking about the “Iranian” factor in the worldview of the modern Azerbaijanis, it is enough to recall that the first anti-Armenian, and then anti-Soviet rallies on the central Lenin Square in Baku were held under a huge portrait of Ayatollah Khomeini.

(33) In historical context, “Pax Persica” is a concept that historians use to describe the policies and period in the Achaemenid Empire that was characterized by relative stability and tolerance towards conquered peoples.

(34) This article was completed before the Iranian-Israeli escalation of June 12-13, as well as the de facto end of Iranian-American negotiations on the “nuclear dossier.”

(35) Dugin A. G., Foundations of Geopolitics, Glossary, https://virmk.ru/read/d/DUGIN/chapt09.htm (download date: 03.06.2025); See the English version at: https://archive.org/details/foundations-of-geopolitics-geopolitical-future-of-russia-alexander-dugin-english/mode/2up (download date: 03.06.2025).