Publication

International Transport Corridors & Their Impact on Regional Security

The relevance of the problem and the concept

of the “International Transport Corridor” (ITC)

The strength of a state’s position in the international system is largely determined by the success of its economic development. This includes its GDP level, technological advancement, raw material resources, industrial capacity, physical geography, the efficiency of its security structures, and its transport and communication infrastructure. All these factors directly influence the economic security of both the nation and its surrounding region.

Throughout history, transport routes have fostered trade growth and laid the foundation for state development. Historically, transport communications have been essential in shaping trade, economic, cultural, civilizational, political, and military relations between nations, civilizations, and continents.

During Ancient and Medieval times, Eastern Asia was connected to the Mediterranean and Europe through a caravan trade route, known worldwide as the “Great Silk Road”. The term was introduced by German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877. The Silk Road emerged following the conquests of Alexander the Great, which expanded knowledge between the East and West and laid the foundation for trade relations. The name “Silk Road” reflects the primary export commodity from China – silk.

Since then, humanity has developed numerous new transit routes, driven by technological progress and economic cooperation as the quality of roads and transportation means remains directly dependent on scientific and technical advancements, as well as economic cooperation and international rivalry.

New roads (transport communications and corridors) always lead to change. These changes can positively impact some geopolitical centers and players, while negatively impacting others – especially those excluded from these projects or forced to participate against their national interests due to military defeats or dependent status.

In fact, transportation and communications are essentially the “lifeblood” of national and global economies. Major historical rivers, maritime and oceanic routes, railways, highways, and the global information network comprise our planet’s communication framework, laying the foundation for intercivilizational dialogue.

At the same time, international transit routes stimulate economic growth for those who benefit from such projects, thereby reshaping global trade and geopolitics. The process of defining new international transport routes often stems from the national interests of major players on the global stage and is shaped by intense geopolitical competition and conflicts. In many cases, it results from imperial ambitions and expansionist policies. Disruptions in the balance of interests among key actors in export-import operations (i.e., the global economy) can lead to external threats, conflicts, and instability at both regional and global levels.

This negative trend in determining key transport corridors is frequently accompanied by local and regional wars. Conflicting parties are often backed by opposing geopolitical centers, which exploit local disputes to establish control over strategic territories and transit routes. This control allows them to influence the functioning or blocking of transport corridors if a project contradicts their national interests or imperial ambitions.

It is worth mentioning that International transport corridors (ITCs) emerge from a combination of economic and geopolitical interests, and they can also cease to exist for the same reasons. Otherwise, the “Great Silk Road”, which appeared in Antiquity, would have continued uninterrupted to this day. While the modern world is reviving this project, it now serves as a new transit route for a technologically advanced China, with different export goods and alternative pathways.

ITCs are shaped by economic and geopolitical shifts, which are often accompanied by conflicts of varying intensity and scale. However, their implementation requires strict security measures, including legal, technical, military, and counterterrorism protections.

Simply put, no one will invest significant financial resources in the construction of extensive, multi-kilometer transit communications and corridors (including road, rail, air, maritime, energy, and cable infrastructure) if a specific section of the route connecting countries, regions, or continents faces a high risk of military conflict, international terrorism, or sabotage warfare.

A clear example of this principle is the containment of Kurdish insurgency in eastern and southeastern Turkey at the turn of the 20th–21st centuries. This was crucial for implementing Azerbaijan’s “Contracts of the Century”, which aimed to establish an alternative Caspian oil and gas transit route to global markets, bypassing Russia.

In February 1999, a collaborative intelligence operation of the United States, Israel, and Turkey led to the capture of Abdullah Ocalan, the leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), at the Greek Ambassador’s residence in Kenya. Ocalan had threatened sabotage operations along the potential transit route for Azerbaijani oil and gas through Turkey, posing a risk not only to Turkey’s security but also to the financial and economic interests of EU nations and major Western and Turkish energy companies (including British Petroleum, Pennzoil, Amoco, Total Energies, and BOTAŞ). His arrest and life imprisonment effectively deprived the Kurdish movement in Anatolia of its central leader.

The containment of the Kurdish threat in Turkey played a salient role in the Istanbul OSCE Summit in November 1999, where the main transit route for Azerbaijani oil was determined–bypassing Russia and passing through Turkey to Europe. At the time, Russia was focused on justifying its military actions in Chechnya, aiming to restore constitutional order, but missed the opportunity to secure Caspian oil transit from Azerbaijan.

In essence, the Chechen incursions into Dagestan (Karamakhi and Chabanmakhi) in the summer of 1999, allegedly aimed at creating an Islamic Confederation in the North Caucasus, were part of a covert operation by U.S., British, and Turkish intelligence to block Russia’s oil transit route from Baku. At the time, Chechnya was controlled by separatists (Basaev, Yandarbiyev, and Maskhadov), who blocked the Baku–Grozny–Novorossiysk pipeline. Moscow proposed an alternative route to the Azerbaijani President Heydar Aliyev, bypassing Chechnya via Dagestan to Stavropol and then to Novorossiysk. However, in response, Chechen militants – allegedly under external influence – ignited conflict in Dagestan, thereby disrupting Russia’s plans for Azerbaijani oil transit control.

Ultimately, the West secured its preferred Caspian oil route from Azerbaijan through two intelligence operations by NATO countries and Israel. This ensured geo-economic entry into the South Caucasus and the formation of new multimodal international transport corridors. Today, having established influence in the South Caucasus, Turkey and the West (U.S. and Europe) are expanding their reach into post-Soviet Central Asia, a resource-rich region.

The Istanbul OSCE Summit in late 1999, attended by U.S. President Bill Clinton, finalized the main transit route for Azerbaijani oil and gas through Georgia, Turkey, and into Europe. The West invested billions of dollars in building pipelines, highways, and railways. In the first quarter of the 21st century, this strategy by London, Washington, and Ankara led to the creation of the “Southern Transport Corridor” (STC) and the establishment of Azerbaijan as a geopolitical hub in the South Caucasus. Due to its strategic location, Azerbaijan is of key interest to Anglo-Saxon powers and Turkey, serving as a gateway to Central Asia under the guise of Pan-Turkism and the modern Organization of Turkic States (OTS).

The ongoing Arab-Israeli war in Gaza is another example of how geopolitical conflicts shape international transport corridors. Specifically, Tel Aviv’s policy regarding the southern territories of the country – effectively the deportation of Gaza’s two-million Arab population – is largely aimed at securing full control over its southern Mediterranean ports, where a key maritime trade route from India to Europe is planned.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the bipolar world order established after World War II, the international community has been experiencing turbulent transformations. The U.S. aspiration to declare itself the sole victor of the Cold War and establish a unipolar world under Washington’s dominance proved unrealistic due to objective contradictions and the presence of multiple power centers seeking to maintain global balance and create a multipolar world structure.

At the Munich Security Conference in February of 2007, Russian President Vladimir Putin publicly challenged U.S. global dominance, calling for respect for the diversity of the modern world. The subsequent period of the first quarter of the 21st century has demonstrated that the world has plunged into chaotic crises, contradictions, conflicts, and local wars. The previous international security system and the UN institution have proven inadequate in addressing new challenges, failing to curb military aggression by stronger powers against weaker and unprotected nations. This is evident in conflicts such as the wars in Iraq and Libya, the Georgian-Russian and Russian-Ukrainian conflicts, the 44-day War in Nagorno-Karabakh, the deportation of Armenian populations, the ongoing civil war in Syria, and the Palestinian-Israeli military conflict in Gaza.

As global transformations unfold, conditions emerge for the formation of new international transport corridors, reflecting the contours of a new world order, rising powers, and new global trade dynamics. Often, the main export commodity itself becomes the subject of intense competition, including conflict-driven rivalries.

For example, since the 20th century, when oil gained strategic importance in the global economy and became industrialized, history has witnessed numerous conflicts and wars over control and ownership of oil resources. These conflicts continue to simmer and could escalate again.

The Soviet Union sought to carefully manage its natural resources, thereby ensuring a regional balance in the exploitation of raw materials without violating the interests of union republics, whose physical geography contained significant reserves of oil and gas. For this reason, accusations against Russia regarding imperial exploitation of national peripheries in the pre-Soviet and Soviet periods do not correspond to reality. Otherwise, Caspian countries today (Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan) would not have such substantial reserves of strategic raw materials, over which a fierce struggle has emerged among global powers and key regional players in the post-Soviet era.

The Caspian oil and gas transport corridors have been a focal point of geopolitical competition since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The emergence of alternative international transport-energy corridors that bypass Russia has enabled major Western energy companies from the UK, U.S., Turkey, France, and Italy to gain access to Azerbaijan’s oil and gas resources. As a result, between 1994 and 2020, a multimodal transport corridor was developed, including: Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan oil pipeline, Baku–Tbilisi–Erzurum gas pipeline, Trans-Anatolian (TANAP) and Trans-Adriatic (TAP) gas pipelines, and Baku–Tbilisi–Kars railway.

A new South Caucasus transport-energy corridor has emerged in Transcaucasia, which has the potential to become one of the key connecting segments of China’s “One Belt–One Road” Initiative (BRI) within the “Middle Corridor” project. In other words, geopolitical adversaries are always attentive to global and regional transformations, traditionally exploiting the temporary weaknesses of their competitors to expand their own opportunities and alter the historically established balance of power. Often, geopolitical ambitions become decisive factors in the implementation of seemingly economic ITC projects.

A clear example of this economic-geopolitical imbalance was the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline, the longest (1,730 km) and most expensive ($3+ billion) alternative route, despite the existence of a safer Baku–Grozny–Novorossiysk pipeline.

Some experts suggest that local conflicts in the Caucasus during the 1990s–2000s (including Karabakh, Abkhazia, and Chechnya) may have been artificially initiated by foreign intelligence agencies (UK, U.S., Turkey, Israel) to block Russia’s transport corridor and Caspian oil and gas transit. According to a 2020 publication, “Western and Turkish intelligence allegedly used Azerbaijan to trigger an internal military conflict in Russia (Chechnya) in late 1994, aiming to disrupt Russian oil pipeline operations”(3).

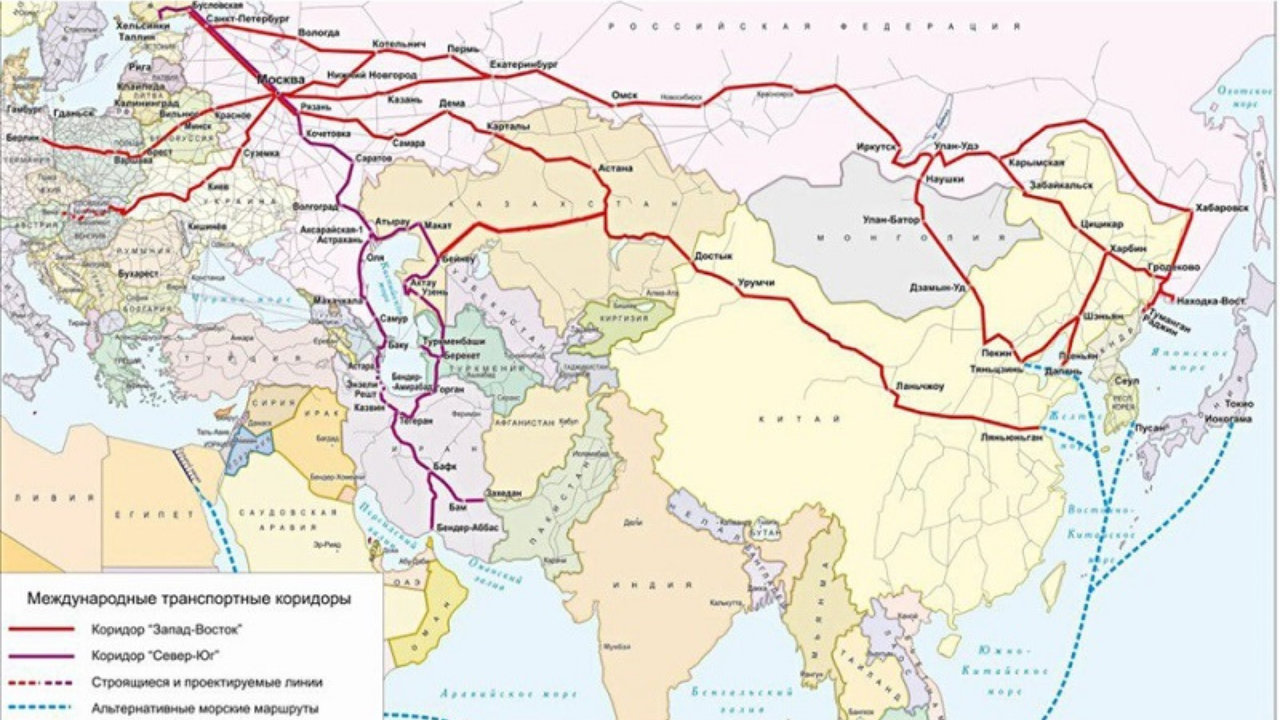

In the context of global geopolitical transformations and integration processes, International Transport Corridors (ITCs), are key factors in the development of the world economy. ITCs involve the creation and operation of stable transport communications between various participants in international economic relations.

ITCs refer to transit transport routes that connect multiple countries into a unified economic system for the movement of passengers and goods. In this context, the term “multimodal ITCs” is often used, meaning several types of transport-communication links, including roads, railways, pipelines, and power transmission lines(4).

A multimodal ITC project aims to establish optimal transit routes from major producers to large consumer markets, integrating various transport and energy networks (road, rail, air, maritime, pipeline, and cable) to ensure regular cargo and passenger movement. This includes the development of highways, railways, ports, airports, and electronic customs and border control systems.

Geography, particularly access to maritime routes, often determines the strategic importance of ITCs. The Black Sea straits (Bosporus and Dardanelles) remain critical geopolitical chokepoints, controlling access to the Black Sea, Mediterranean, and Atlantic Ocean. And the one who controls the Bosporus and the Dardanelles remains in the ranks of key global geopolitics.

In its turn, the opening of the Suez Canal on November 17, 1869, revolutionized global maritime trade. The construction of this lock-free canal in Egypt connected the Mediterranean and Red Seas, providing the shortest maritime route from India to the Atlantic Ocean – eliminating the need to circumnavigate Africa and reducing the sea journey by 8,000 km.

ITCs generally stimulate national economies in the countries they traverse. However, they can also serve as soft power tools for dominant geopolitical players, influencing weaker participants in global trade networks. This makes ITCs a subject of interest in politics, economics, security, and academic research (political science, economics, sociology, law, etc.).

It must be noted that the Russian academic research has produced a diverse range of studies on International Transport Corridors (ITCs) in recent years. These include dissertations, monographs, articles, and reports, focusing on the theoretical and methodological foundations of ITC development, as well as their economic and geopolitical impact on various countries, regions, and continents.

The following scholars have made notable contributions to this field:I. Abbasaliev, L. Albrecht, P. Biryukov, L. Vardomsky, A. Volodin, V. Voronov, N. Grigoryev, A. Gorokhova, E. Gladskikh, I. Ermakov, K. Zhuravlev, M. Komov, V. Lazarev, E. Levitin, M. Turaeva, K. Khlopov, and E. Shustova. A comprehensive study of issues related to International Transport Corridors (ITCs) contributes not only to the formation of a community of specialists but also to the development of entire academic schools. These schools may have diverging or conflicting views, as their conclusions often reflect not only the objective reality of ITC formation but also the political biases of experts, influenced by the political stance of their home countries(5).

The study of issues related to the economic and geopolitical impact of International Transport Corridors (ITCs) on national, regional, and global security are being conducted. The South Caucasus, due to its physical geography and diverse geopolitical orientations of regional actors, as well as the varied interests of external players seeking to maintain or establish influence, is transforming into both a zone of heightened external attention and a key connecting hub for international trade transit along the East–West and North–South routes.

The South Caucasus serves as an important route for planned multimodal ITCs, which – if external and internal interests are balanced – could bring regional peace and security. However, such a balance has not yet been achieved, and the region continues to face escalating contradictions and conflicts.

2. Conflicting Interests of Global and Regional Players in ITC Formation

Vladimir Lenin in his times had famously stated, that “Politics is the concentrated expression of economics”(6). This principle has been proven over time, as a state’s primary task is to develop a strong economy, without which it is difficult to maintain power and ensure national security against external threats. If we analyze the policies of key global and regional states through the lens of economic interests in ITC projects, we can conclude that where there is big money, there is always a conflict of interest. Naturally, wealthy nations constantly seek greater enrichment, often at the expense of weaker and less developed countries.

Regarding the constructive significance of ITCs, expert I. Abbasaliev notes: “International transport corridors, particularly Eurasian ones, serve as a fundamentally new mechanism for international cooperation and a factor aimed at overcoming the growing turbulence in intergovernmental relations. The instability of the global political landscape and increasing foreign policy risks have led to a trend of prioritizing national agendas at the expense of international integration processes. This challenge is constructively addressed through new organizational frameworks, one of which is international transport corridors”(7).

In other words, I. Abbasaliev underscores the constructive role of ITCs, arguing that such international economic projects help overcome crises and turbulent relations between states. He believes ITCs redirect national conflicts into a more constructive framework through trade development and international integration. This perspective is constructive, provided that all ITC participants uphold equal rights, stability, security, and mutually beneficial partnerships — excluding violations of sovereignty, geopolitical ambitions, and the use of force.

However, this optimistic characterization of ITCs, which dismisses the presence of conflicting interests among major geopolitical players during the development and implementation of such projects, suggests either an incomplete understanding of the subject or a biased approach to ITC concepts regarding participants, routes, and control mechanisms. Otherwise, all ITC projects, regardless of their initiators and developers, would receive universal external support, and rationalism and integration benefits would prevail in any beginning.

A convincing example of this issue is the current state of Armenia-Azerbaijan relations. Azerbaijan, having failed to fulfill any provisions of the trilateral agreement (Azerbaijan, Armenia, Russia) signed on November 9, 2020, insists that one of the conditions for signing a peace treaty with Armenia is Clause 9 of the agreement — the unrestricted and uncontrolled opening of the so-called “Zangezur Corridor” to connect Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic (NAR) with Turkey.

The Armenian government has expressed a willingness to discuss the unblocking of transport communications, including Azerbaijan’s connection to Nakhchivan via the Meghri region. However, Armenia refuses to consider this route as a “corridor” that would compromise its sovereignty. This contradiction has persisted for several years, with no resolution in sight, likely due to conflicting interests of key external players.

In other words, the prospect of trade transit and financial profit has not yet become a convincing argument for regional unity or for external forces interested in the South Caucasus. If the U.S.–China “tariff war” initiated by President Donald Trump continues, how will Washington accept the “Middle Corridor” for Chinese goods transit through South Caucasus countries to the West (Turkey and the EU), bypassing Russia?

Meanwhile, historical practice shows that some ITCs are developed and implemented at the expense of other major players and smaller states. These corridors often have political motivations, aiming to secure economic and geopolitical advantages at the cost of others’ security. A clear example is the formation of the Southern Energy and Transport Corridor, which connects Azerbaijan through Georgia to Turkey and Europe, bypassing Russia.

In the late 1990s, the United Kingdom and the U.S. were unable to implement the proposed International Transport Corridor (ITC) in the South Caucasus in a more cost-effective manner – specifically, by reducing its length through the Zangezur route in southern Armenia. As a compromise condition for Armenia’s participation in the project and the subsequent exclusion of Russia from the region, the U.S. proposed a territorial exchange between Yerevan and Baku as a solution to the Karabakh issue. This plan involved transferring the territory of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) and the Lachin Corridor to Armenia, while part of the Meghri region would be given to Azerbaijan. However, this compromise failed to materialize due to polarized opinions in Baku and Yerevan. In Azerbaijan, the resignation of presidential foreign policy advisor Vafa Guluzade and Foreign Minister Tofig Zulfugarov disrupted negotiations. In Armenia, the parliament shooting on October 27, 1999, which resulted in the assassination of Prime Minister Vazgen Sargsyan and Speaker of the National Assembly Karen Demirchyan, further stalled the process. Today, the Zangezur route is once again relevant in the context of China’s Middle Corridor project within its ITC initiative.

The conflict of interests among Arab states (Saudi Arabia and the UAE), Israel, and Turkey is particularly evident in the case of India’s ITC, with repercussions in the Palestinian Gaza Strip.

To better understand the nature of conflicting interests in ITC projects during the first quarter of the 21st century, it is necessary to examine the key global and regional players involved.

The United States, positioning itself as a global player, actively participates in all major economic projects, including ITCs – either as a developer-participant or as an opponent-disruptor. The U.S. employs various pressure tactics against its competitors and adversaries, including:

- Strict economic and financial sanctions (e.g., against North Korea, Iran, Russia, and China).

- Financial, investment, and technological support for the rise of new economic centers (e.g., China and India).

- Initiation of local conflicts to block or advance specific ITC projects (e.g., in the Middle East and South Caucasus).

- Direct (full or partial) investment in profitable and agreed-upon ITC projects.

- Participation of American multinational corporations in new ITCs.

In his 1997 book “The Grand Chessboard”, Zbigniew Brzezinski outlined the geopolitical imperatives and U.S. strategy for establishing control over Eurasia in the 21st century, particularly over the post-Soviet space. Brzezinski argued that Ukraine’s final separation from Russia, with the establishment of a pro-Western political regime in Kyiv, would allow the United States to maintain its status as the world’s “sole superpower” and prevent the resurgence of a powerful Russian state in Eurasia. As a follower of Halford Mackinder’s Anglo-Saxon geopolitical school, Brzezinski viewed global politics as a struggle between maritime and land-based civilizations.

To prevent Russia’s resurgence, Brzezinski proposed a strategy for U.S. expansion into Eurasia, relying on key “geopolitical centers” based on their strategic geographic locations. He identified Ukraine, Turkey, Iran, Azerbaijan, and South Korea as critical geopolitical pivots.

Regarding the post-Soviet south, Brzezinski specifically noted: “An independent Azerbaijan, connected to Western markets via oil pipelines that do not pass through Russian-controlled territory, also becomes a major conduit for advanced and energy-consuming economies to access the energy-rich republics of Central Asia”(8).

In other words, the U.S. considers Azerbaijan’s geography as a vital international corridor (both energy and transport) linking the West to Central Asia, bypassing Russia – which creates conflicting interests among the major global players.

In order to weaken and eventually push Russia out of its historically dominant regions, Brzezinski proposed using geo-economic tools to export natural resources (primarily energy) from the Caspian Basin and later Central Asia, bypassing Russia, to global (especially European) markets.

Recognizing China’s growing influence in global markets, the U.S. is now actively restricting Chinese trade expansion. The trade war initiated by President Donald Trump was not only an attempt to shield the American market from Chinese goods, threatening China’s access to a $700 billion market, but also a strategic move against China’s “One Belt–One Road” Initiative. Given Europe’s anti-Russian sanctions due to the Ukraine conflict and U.S. tariffs on European goods, it is probable that Beijing will likely seek to expand exports to the EU. This could lead to renewed U.S.–China competition over South Caucasus transit routes.

The United Kingdom, historically a key architect of geopolitical conflicts over Eurasian resources, has sought to revive its strategic approach following the collapse of the Soviet Union and Russia’s temporary weakening at the turn of the century. London aims to reintroduce the tactics of the “Great Game”, systematically pushing Russia out of its historical spheres of influence to exploit natural resources and extract wealth.

As part of this strategy, the UK is providing support for alternative ITC projects that bypass Russia, potentially reshaping the global geopolitical “chessboard”. London has been a leading initiator of the Southern Transport Corridor in the South Caucasus, relying on Turkey and Azerbaijan. It also backs the Middle Corridor, which passes through the Caspian Sea and Azerbaijan into Turkey and Europe. Additionally, the UK does not rule out the future implementation of the “Turan ITC”, allowing Turkey to expand through the South Caucasus into Central Asia, or as Ankara now refers to it — “Western and Eastern Turkestan”.

The head of MI6, Richard Moore, has been closely involved in this project. During his visit to Baku in November 2024, Moore delivered a speech at ADA University, proposing the formation of a Turkic alliance, modeled after the Anglo-Saxon “Five Eyes” intelligence network (FVEY). London also seeks geopolitical revenge against Russia’s victory in the “Great Game” in Turkestan at the turn of the 19th–20th centuries.

China is not merely the initiator of the mega-project “One Belt–One Road” initiative, aimed at exporting Chinese goods to Europe. It is also searching for alternative land and maritime routes, using the principle “consumption drives demand” to draw smaller and mid-sized regional countries into its ITC orbit.

In other words, Communist China is attempting to achieve global dominance not through the export of Marxist–Leninist ideology (with Maoist elements) but through Chinese-manufactured goods. Beijing is highly interested in expanding into the European market, as a significant portion of China’s foreign trade is tied to Europe ($847 billion in 2022, $782.9 billion in 2023, $785.82 billion in 2024)(9). Consequently, China views India’s competing ITC project – which passes through the Middle East into Europe – with caution and seeks to counter Turkey’s Pan-Turkist ambitions to expand into the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) with its center in Urumqi.

India is experiencing rapid economic growth and external support (investment and technology) from the U.S. and EU (especially France). As a result, New Delhi is keen on developing its own ITC to Europe, both through the Middle East and the South Caucasus – despite opposition from China, Pakistan, and Turkey.

Turkey has emerged as a key transit hub for strategic raw materials (oil and gas) from the Caspian Basin to Europe, thanks to its close ties with the UK and Turkic republics of the post-Soviet space, particularly Azerbaijan. This trend is reinforced by mutually beneficial trade and energy cooperation with Russia (including the Blue Stream and Turkish Stream pipelines, as well as the gas hub megaproject) and Ankara’s strategic expansion into Central Asia through the Turan Corridor. The latter poses a potential geopolitical challenge for Russia, Iran, China, and India.

Russia, as the largest country in the world and the central power in Eurasia, is the initiator of the “North–South” ITC. Its vast natural resources and strategic geography allow it to serve as a key partner for both the Global South and the collective West. Russia’s control over most of the Arctic will play a critical role in global trade and transit in the foreseeable future.

However, the “North–South” ITC faces challenges due to ongoing tensions with the West over the Ukraine conflict (especially with European nations) and Turkey’s geopolitical ambitions in Central Asia. In this project, Iran is Russia’s most important partner for access to the Indian Ocean, but Tehran opposes Azerbaijan’s growing influence and could become a target of external aggression from the U.S. and Israel.

3. Modern ITC projects and their impact

on economic development and geopolitics

Eurasia is shaping the new global order, defining resource distribution and trade, which drives the creation of new ITC projects that will directly impact economic progress and geopolitical transformations in the 21st century. These projects will also influence global and regional security systems. Key ITC projects include: China’s “One Belt–One Road” Initiative (BRI), India’s IMEC, Turkey’s “Middle (or “Turan”) Corridor”, and Russia’s “North–South” ITC.

China’s “One Belt–One Road” project (BRI) was first announced by President Xi Jinping in September 2023 during his visits to Kazakhstan and Indonesia.

Specifically, the Chinese leader proposed integrating land and maritime trade routes to facilitate faster delivery of goods from China to Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe. The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs has incorporated the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) into Beijing’s diplomatic strategy and the 13th Five-Year Plan.

The core objective of the BRI is to develop a new model of international cooperation, strengthening existing bilateral and multilateral mechanisms with China’s participation. Inspired by the ancient Silk Road, BRI seeks to create new regional economic partnerships, stimulate economic prosperity, enhance cultural exchanges, and promote peace and sustainable development.

The BRI covers most of Eurasia, connecting developing economies (including post-Soviet republics) with developed nations. The initiative’s economic scale is estimated at $21 trillion, with over $1 trillion invested by 2022.

The “One Belt–One Road” Initiative (BRI) encompasses the creation of 3 trans-Eurasian economic corridors:

- “Northern Corridor” (China, Central Asian countries, Russia, and Europe).

- “Middle” or “Central Corridor” (China, Kazakhstan, Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, Georgia/Armenia, Turkey/Iran, and Europe).

- “Southern Corridor” (China, Southeast Asian countries, South Asia, and the Indian Ocean).

The name “One Belt–One Road” does not fully reflect the complexity of China’s strategic vision, as the initiative encompasses multiple pathways, not merely a single route.. Additionally, the “Middle Corridor” has two competing routes – one passing through Azerbaijan, Georgia, Armenia, and Turkey, while the other passes through Iran, Armenia, and Georgia.

Beijing considers BRI not just a large-scale project but a vital necessity, as the overproduction in Chinese factories requires access to a large and solvent market, such as the EU. The West (U.S. and Europe) accounts for more than half of China’s foreign trade, and without these markets, China stands to lose over $1.5 trillion, leading to economic stagnation and regression. Additionally, China aims to develop bilateral trade relations with smaller Eurasian economies, fostering constructive partnerships while gradually increasing their economic and geopolitical dependence on China.

In the context of the new administration of the U.S. President Donald Trump’s anti-China measures, which include the imposition of tariffs on Chinese goods reaching 145% and the exertion of pressure on South American countries to limit their trade ties with China, there is a possibility that so-called “Panama practice” may be expanded by Washington to other nations and regions. In response, Beijing is considering the EU’s similar dissatisfaction with the U.S. trade war and is seeking the prospect of an alliance with Europe to increase Chinese exports.

Regarding Russia, China has proposed the Northern ITC route, but the Russia–Ukraine crisis and Western sanctions have effectively blocked the Russian segment of China’s transit. As a result, the “Middle Corridor” – passing through Kazakhstan, the Caspian Sea, and the South Caucasus – poses a potential challenge to Russia, strengthening China’s regional economic and geopolitical influence in Central Asia and the South Caucasus.

China has already established pragmatic and strategic partnerships with Central Asian republics (especially Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan) and Azerbaijan. A notable development was the official visit of Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev to Beijing in April 2025, during which the Azerbaijan–China Declaration on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership was signed. This agreement positions Azerbaijan as a regional hub for Chinese goods transit to the West.

China has announced its intention to integrate Armenia into its “One Belt–One Road” Initiative (BRI) transport network. Min Chen, the Chinese chargé d’affaires in Yerevan, stated that Armenia could participate in the “Middle Corridor”, facilitating trade flows to Turkey and Europe(10). This means that Armenia’s transit route – either through Tavush and Gyumri or Zangezur (Meghri) – could become a key component of the “Middle Corridor”. The Tavush–Gyumri route is shorter and more cost-effective compared to alternative routes (Zangezur or Georgia), maintaining strong competition with neighboring Georgia and Iran.

The “Middle Corridor” also includes Georgia’s transit route, thereby facilitating Chinese goods transport via the Black Sea to Europe. To support this, China has invested in the construction of the deep-water Anaklia Port, which will be capable of handling ocean container ships. Some experts believe that Western tensions with Georgia have escalated due to China’s involvement in the Anaklia Port project.

The United States is the main opponent of China’s BRI, expressing concerns over Beijing’s policy regarding Taiwan, its strategic partnership with Russia, and its growing influence on the EU economy. As a result, U.S.–China trade volume declined by 12.2% in 2023, reaching a total of $607.01 billion(11). In the same year, the U.S. began supporting India’s alternative ITC to Europe, and Donald Trump intensified tariff hikes on Chinese goods.

The Indian project of transport corridor to Europe (India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor – IMEC). In September 2023, after the G-20 summit in New Delhi, the U.S. President Joseph Biden announced the creation of India’s ITC to Europe (IMEC). He stated that the U.S., the EU, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Israel, Jordan, and India had finalized a historic agreement for a new economic corridor connecting India, the Middle East, and Europe.

IMEC’s strategic investments in maritime and rail transport aim to boost global trade, ensure reliable clean energy supplies, and fortify internet cable infrastructure, and Middle Eastern economic integration. The project serves as an alternative to China’s BRI and is a key U.S. initiative to counter China’s growing influence.

That is why China did not participate in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit held in New Delhi in September 2023. Meanwhile, India’s transit plans face obstacles due to the ongoing Palestinian-Israeli conflict in Gaza, which affects planned trade routes along the Mediterranean coast. Additionally, this conflict delays U.S. efforts to establish trade relations between Er-Riyadh and Tel Aviv.

Turkey, having embraced the advantages of being a transit hub, seeks to join India’s IMEC and serve as a logistical center for goods passing through Mersin Port. This may explain President Recep Erdoghan’s strong opposition to Israel’s demographic policies in Gaza and his proposal for a Turkish-led resolution to the Palestinian issue, which includes granting Ankara an international mandate to guarantee Palestinian security and deploying Turkish peacekeeping forces to Gaza’s maritime port.

However, Turkey’s participation in IMEC is not decided in New Delhi or Tel Aviv, but rather in Washington. It largely depends on Ankara’s alignment with U.S. ambitions in the Middle East and post-Soviet space. This dynamic has had a direct impact on Turkey, including banking sector issues since early 2024 and Turkey’s refusal to process Russian transactions. Additionally, the defeat of Erdoghan’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) in the March 31, 2024 municipal elections – in favor of pro-Western opposition – signals challenges for Erdoghan’s sovereign policies. The Turkey–Israel ongoing tensions in Syria also remain a key concern for the U.S., which seeks to prevent a military escalation.

Iran, geographically close to India, could become a participant in IMEC via the Persian Gulf. The Iranian route for Indian transit would follow a northern branch through Armenia’s Zangezur region, then Georgia, the Black Sea, and into Europe. This sheds light onTehran’s opposition to Armenia granting the “Zangezur Corridor” to Turkey, which is currently framed as part of China’s BRI transit network.

Iran has leveraged the Palestinian-Israeli conflict to demonstrate the capabilities of its proxy forces in Yemen, Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq against Western interests. In the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, Iran-backed Houthi forces have effectively disrupted Anglo-American maritime trade, rendering the Suez Canal passage inefficient during the Gaza conflict. As a result, insurance rates for tankers have surged, and many cargo ships have been compelled to reroute. Consequently, IMEC holds significant economic and geopolitical importance for Iran, and Tehran will continue to push for its inclusion.

If the U.S. and Iran reach a compromise on nuclear negotiations, and American-Israeli aggression against Iran is curbed, Tehran could see partial sanctions relief, leading to IMEC’s activation for Iranian exports – particularly natural gas – to global markets, especially the EU. In this scenario, Armenia could become a crucial bridge for Iran’s trade with Europe and Russia.

As India’s transit project unfolds, parallel geopolitical conflicts are shaping national and regional security dynamics across the Middle East and South Caucasus.

Turkey’s project of energy and transport corridor (“Middle Corridor” or the “Turan Corridor”) has gained strategic importance due to its geopolitical location at the intersection of Asia, Africa, and Europe. By implementing key energy projects, Turkey has positioned itself as a critical transit hub for Azerbaijani energy exports to Europe, bypassing Russia. Ankara continues its policy of energy diversification and trade pragmatism, aiming to strengthen its status as a regional power through Neo-Ottomanism, Neo-Pan-Turkism, Turkish Eurasianism, and the Turkish Axis. In essence, Turkey seeks to establish a Turkic geopolitical pole within the multipolar world order, serving as a bridge between Asia and Europe.

Following the military success of the Turkey-Azerbaijan alliance in Nagorno-Karabakh (2020–2023), Turkey has pursued an active policy of Turan formation, aiming to secure access through Armenia’s Zangezur Corridor into Azerbaijan and further into Turkic nations of Central Asia, which possess rich energy and mineral resources. Ankara’s economic strategy for developing newly independent Turkic states is carried out through both the Organization of Turkic States (OTS) and China’s “One Belt–One Road” Initiative (BRI).

That is why the implementation of the “Middle Corridor” would allow Turkey to control the Zangezur route and expand into historical Western and Eastern Turkestan. Additionally, Ankara seeks to capitalize on Russia’s temporary geopolitical and economic challenges, particularly its ongoing conflict with the West over Ukraine, to gain access to Turkmen gas, Kazakh uranium, and the broader Turkic world.

In negotiations with the U.S. and UK, Turkey presents its Eastern policy as part of NATO’s strategy, arguing that NATO’s entry into Central Asia via Turkey would create a buffer zone between Russia, Iran, and China. Within this framework, Turkey is also developing the “Turan Army”, envisioned as sort of an Asian bureau of NATO.

However, the “Middle Corridor” project contradicts Iran’s national interests and security. Russia, while maintaining a partnership with Turkey, is unlikely to allow Ankara to weaken or displace Moscow’s centuries-old presence in the South Caucasus and Central Asia. Meanwhile, China relies on its economic and military strength to counter Turkey’s imperial ambitions in Xinjiang (XUAR). The West (U.S., UK, and France) may attempt to exploit the ongoing Armenia–Azerbaijan tensions to subordinate Turkey within broader regional operations in the South Caucasus.

It’s no coincidence that in the spring of 2025 in Samarkand (Uzbekistan) the first summit of EU leadership and the heads of the republics of Central Asia took place. Given Europe’s raw material shortages due to sanctions against Russia and the limited energy resources of Azerbaijan, the EU seeks to develop new transit routes to connect with Central Asia. This project requires significant investments, which Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Central Asian countries currently lack. In Samarkand, Brussels pledged €12 billion for communications, energy, and infrastructure projects.

Russia’s project of “North–South Transport Corridor” (NSTC). Russia, as the largest country in the world and Eurasia, cannot remain detached from major ITC projects. Its geography itself serves as a critical transit link between West and East, North and South. Russia hosts key Eurasian transport routes, which continue to be modernized within EAEU, SCO, and BRICS integration frameworks. As the dominant Arctic power, Russia is also developing new northern ITC routes through the Arctic.

However, due to the ongoing Russia–Ukraine conflict and Western sanctions, the world faces a severe geopolitical crisis. This policy has damaged economic interests, particularly continental Europe, as Western intelligence operations have disrupted key Russian energy exports to the EU–notably through sabotage of Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines–causing irreparable harm to Europe’s energy security.

In September 2024, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz called the “Nord Stream” pipeline explosions in the Baltic Sea a terrorist act, urging security agencies and prosecutors to investigate and hold those responsible accountable. In August 2024, German media outlets ARD, Süddeutsche Zeitung, and Die Zeit reported that Berlin issued an arrest warrant for Ukrainian diver-saboteur Vladimir Zhuravlev, suspected of carrying out the “Nord Stream”. According to German sources, a six-person sabotage team was involved in the operation(12).

Given the temporary restrictions and blockade of Russian transit routes to Europe, Moscow is actively expanding ties with China, India, Turkey, Iran, the Arab world, Southeast Asia, and Africa. As part of this diplomatic strategy, Russia is promoting the multimodal “North–South” ITC project.

One of the land routes for the “North–South Transport Corridor (NS) passes through Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, Iran, and Turkey. The Zangezur route has once again become a geopolitical focal point, as it could accommodate 3-4 different ITCs (including Russian, Chinese, Indian, and Turkish). The struggle for control over Zangezur involves conflicting interests among major geopolitical players and smaller nations, including Russia, the U.S., the UK, Turkey, Iran, China, India, Azerbaijan, and Armenia.

Russia’s primary objective in the NS ITC is to secure access to the Indian Ocean via the Persian Gulf. Iran, which has coastlines along both the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf, has long considered a 700–750 km water canal project, estimated at $10 billion, to connect these two basins. This would reduce reliance on the Black Sea straits and provide Eurasian nations with a more direct maritime route through the Persian and Oman Gulfs, the Strait of Hormuz, and into the Indian Ocean. Naturally, the implementation of such a project in Iran has become a major geopolitical issue, sparking controversies among global and regional players.

Russian expert Artem Leonov notes that the Russia–Iran Canal could provide the shortest Eurasian trade route. According to Leonov, the 750 km Caspian–Persian Gulf Canal project was originally developed in 1910 during the Russian Empire(13).

Later, the UK and the U.S. actively opposed the canal’s construction to prevent Russia’s expansion southward and block its access to the Indian Ocean. Economist Valentin Katasonov highlights that in 1943, during the Tehran Conference, Joseph Stalin discussed the Caspian Canal project with Iranian Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, but Iran, under U.S. influence, did not pursue the idea(14).

In 1996, an Iranian delegation visited the Volga–Don Canal and Volga–Baltic Waterway, holding talks with Rosmorrechflot on joint feasibility studies for the Caspian–Persian Gulf Canal. In August 2018, Caspian littoral states signed the Aktau Agreement, defining a new legal status for the Caspian Basin, removing legal barriers to the Canal’s construction. The planned Caspian route would pass through neutral waters, avoiding national maritime zones. In Iran, the Canal would run from the port of Anzali on the southern Caspian, following the Sefidrud, Karkheh, and Nahr al-Kahla rivers, eventually connecting to the Shatt al-Arab and the Persian Gulf.

This transport artery would create a direct and shortest maritime transit route from the Baltic region to the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. For many countries, access to the Indian Ocean via the Caspian Canal would be twice as short compared to the Bosporus–Dardanelles–Suez–Red Sea route.

In 1997, according to Leonov, the U.S. warned Iran that any companies or organizations involved in the Caspian Canal’s construction would face severe economic sanctions, as the project would weaken U.S. geopolitical influence(15).

4. Geographical Significance of the South Caucasus

The South Caucasus (Transcaucasia) has historically served as a strategic crossroads in Eurasia. However, its ethnic diversity and internal contradictions, combined with the interests of major geopolitical players, have often complicated natural competition and cooperation.

Throughout history, depending on the political status of the region, the South Caucasus has either lost its geopolitical intensity, becoming a province of a dominant power, or gained strategic importance due to its position as a transit hub. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the South Caucasus – similar to the early 20th century – has once again become a competitive geopolitical zone. Its conflict potential, combined with valuable geography and natural resources, has led to the formation of a new status quo, involving Russia, the U.S., the UK, the EU, China, India, Turkey, and Iran.

For Russia, Transcaucasia remains a priority of southern geopolitics and economic integration, given the historical tradition of presence in the region, centuries-old relations and cohabitation within a single state, security interests, mutually beneficial transit of goods, and the advantages of a multipolar world.

The USA, the United Kingdom, and the EU are aimed at limiting Russian influence and presence in the South Caucasus, initiating various projects to push Russia out of the region, establish their own control here, extract natural resources, and enter the adjacent region of Central Asia.

China and India plan to use the territory of the South Caucasus for the implementation of international transport corridors (ITCs) with the aim of shortening the transit time for delivering goods to Europe, economically absorbing the region, and enhancing their own competitive capabilities.

Turkey regards the South Caucasus in the context of expanding its status as a regional power, implementing the doctrine of neo-panturanism, and obtaining an important transit role in the traffic of strategic energy resources (oil and gas) to the European market at preferential prices.

Iran is trying to restore its influence in Transcaucasia with the prospect of breaking through economic isolation, implementing profitable ITC projects to access the markets of Europe and Russia, as well as eliminating threats to its own security arising from the Turkish doctrine of neo-panturanism and the strategy of NATO’s expansion into post-Soviet Eastern territories.

Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia, taking into account a complex of internal and external contradictions, are in the process of determining their foreign policy and economic vector, upon which their security and the prospects for economic development depend.

It must be noted that the “Middle Corridor” and the “North-South” ITC may clash, as Turkey seeks a corridor to Central Asia (the so called “Turan”), while Russia prioritizes access to the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean via Iran. Turkey’s and NATO’s eastward expansion has become more tangible since 2020, following the Turkey–Azerbaijan military success in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Iran opposes the “Middle Corridor”, as Tehran does not want the Turkic influence to strengthen along its northern borders. Iran fears ethnic separatism among its Turkic-speaking population, particularly in Tabriz, and rejects the idea of Armenia losing control over the Zangezur route, which provides Iran access to Georgia, Russia, and Europe. Additionally, Tehran seeks to maintain control over Nakhchivan and Azerbaijan’s dependence, which resulted from the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

India is an indirect competitor to the China–Turkey ITC through Armenia’s Syunik region, as New Delhi plans to develop its own transit route via Iran, Armenia, Georgia, Russia, and Europe. India also maintains geopolitical tensions with China, Pakistan, Azerbaijan, and Turkey.

Georgia fears that opening of the so-called “Zangezur Corridor” (which benefits Turkey and Azerbaijan) or the Tavush–Gyumri–Kars route could reduce transit volumes through the “Southern Transport Corridor” (STC) by half, thus undermining Georgia’s economic stability.

Russia’s 7,500 km “North–South” ITC aims to connect Europe and Russia via Azerbaijan to Iran, the Persian Gulf, and the Indian Ocean. Azerbaijan supports this project, as it would increase trade traffic and strengthen ties with Russia and Iran. Baku has modernized and constructed new infrastructure, including roads, bridges, and customs checkpoints, up to Astara on the Iranian border.

However, in this project, Iran is for now merely verbally approving everything, signing agreements, and smiling during meetings. Tehran is in no hurry to complete the construction of its portion of the infrastructure along the Rasht–Qazvin–Bandar Abbas line. Meanwhile, Moscow is ready to invest in and participate in the joint construction of the road. Clearly, Iran does not wish for Azerbaijan to be strengthened, and perhaps it is linking the “North–South” project with the implementation of the Indian ITC through Armenia.

That is why Heydar Abdikerimov, the head of the “Trans-Caspian International Transport Route Association” states: “We have the North–South corridor: Astara–Rasht–Qazvin. This corridor was announced long ago, but it has not progressed. Azerbaijan has fulfilled all obligations… But Iran has yet to build its roads, which slows down the route’s development”(16).

Iran’s wait is obviously connected with Tehran’s unwillingness to strengthen Azerbaijan on its northern borders by granting it a monopoly on the connecting control of the “North–South” ITC between the Russian Federation and the Islamic Republic of Iran. The Iranians see geographically alternative possibilities for mitigating Azerbaijan’s “monopoly” role in this project. In particular, the “North–South” ITC can, aside from the route through Azerbaijan, include three other alternatives: Russia–Georgia–Armenia–Iran, Russia– Kazakhstan–Turkmenistan–Iran, and Russia–Caspian Sea–Iran. In the development of such infrastructural logic, Russia minimizes its dependence on Azerbaijan – which listens to Turkey’s opinion and did not join the Russian (Eurasian) integration unions (CSTO and EAEU) after its success in the 2020 Karabakh War and the favorable position of the Russian side. At the same time, the availability of these alternative transit routes for goods along the “North–South” ITC will allow Moscow to integrate all the Caspian and Transcaucasian post-Soviet republics into a unified system of economic ties as well as to have an independent maritime route for direct access to Iran.

In such a perspective, Iran will no longer have any suspicions regarding the undesirable scenario of strengthening the Turkic axis through the dominance of the Turkish-Azerbaijani tandem. Accordingly, processes and road construction works are being accelerated. Today, even China is interested in the availability of alternative transit segments for its “One Belt– One Road” Initiative (including within the South Caucasus through Azerbaijan and Armenia). Russia is even more entitled to count on the expansion of transit route modules.

Investment and quality of transit infrastructure are critical factors in the implementation of any ITC project. In this regard, Azerbaijan and Georgia have outpaced Armenia in the South Caucasus, as external players seeking alternative transit routes bypassing Russia have provided significant investments to Baku and Tbilisi. These investments have supported the construction of transit infrastructure, including oil and gas pipelines, railways, highways, deep-water ports, and bridges. Armenia, however, was excluded from regional transport corridors due to the unresolved Nagorno-Karabakh issue.

Despite this, Armenia’s geography remains highly attractive for external powers seeking optimal and shortest transit routes. Countries such as Iran, Turkey, Russia, India, China, and the EU have expressed strong interest in Armenia’s potential role in ITC development.

In October 2023, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan presented the “Crossroads of Peace” project at the IV Silk Road International Forum in Tbilisi. This initiative aims to modernize Armenia’s transit infrastructure, facilitating West–East and North–South trade routes. However, Armenia has yet to make significant progress beyond presentations and declarations, lacking real modernization efforts in logistics and international transit services.

If external stakeholders (such as China, India, Russia, Iran, Europe, and possibly Turkey) invest in Armenia’s transit infrastructure, the “Crossroads of Peace” project could become a key transit hub in the South Caucasus. However, high-quality transit services will require enhanced security and communication control. In this regard Armenia cannot rely on the trilateral online Agreement of November 9, 2020, as 8 out of 9 provisions were not fulfilled by Azerbaijan and Russia. Russia’s reference to Clause 9 of the Agreement delays resolution efforts.

At the same time, given Armenia’s strategic partnership with Russia, Yerevan and Moscow could sign a bilateral agreement integrating the “Crossroads of Peace” project with the “North–South” ITC, ensuring comprehensive cooperation on transit security.

Thus, international transport corridors contribute to economic development, the formation of new trends in world trade, and the contours of global and regional security.

The period from the development to the implementation of an ITC project involves not only the coordination with likely transit participants on procedural, organizational, economic, legal, and other measures but is also often associated with sharp conflicting interests, the neglect of which may eventually lead to more negative consequences.

(1) Doctor of Political Sciences, PhD in Law, Professor. Graduated from the History Department of Saratov State University named after N. G. Chernyshevsky. Historian, political scientist, expert on conflictology, politics and security; research interests include Turkology, Iranian studies, Armenian studies (including the Karabakh problem), and Caucasian Studies. Author of the fundamental scientific research monograph “Panturkism in Turkey’s Geostrategy in the Caucasus”, as well as hundreds of scientific and analytical articles in various publications.

(2) The article was submitted to the editors on 28.04.2025.

(3) Svarants A., Nagorno-Karabakh against the Azerbaijani-Turkish terrorist coalition // News of the SAR. 2020. October 27.

(4) See: Transport corridors of Asian Russia: status and prospects. (in Rus.), https://bstudy.net/650516/politika/mezhdunarodnye_transportnye_koridory_natsionalnaya_bezopasnost_rossii (download date: 23.09.2024).

(5) See: Abbasaliyev I.S. The Role of Transport Corridors in International Cooperation (Based on the Example of the Caspian Region) // Bulletin of the Northern (Arctic) Federal University. Series: Humanities and Social Sciences. Moscow, 2022. Vol. 22. No. 3; Volodin A.G., Volodina M.A. The North–South International Transport Corridor Project as a Factor in the Possible Strengthening of Russia’s Foreign Economic Relations // Contours of Global Transformations: Politics, Economics, Law. Moscow, 2019. Vol. 12. No. 6. Pp. 29–42; Svarants A. Nagorno-Karabakh against the Azerbaijani-Turkish terrorist coalition // News of the SAR. 2020. October 27; Turaeva M.O., Gorokhova I.V. The Importance of National Interests in the Transport Sphere for Ensuring Russia’s National Security // Federalism. Moscow, 2022. Vol. 27. No. 3 (107). pp. 125–138 and others.

(6) Lenin V.I., Once again about trade unions, about the current situation and about the mistakes of Comrades Trotsky and Bukharin // PSS. 5th ed. Moscow: “Political Literature”, 1969. Vol. 42. P. 278.

(7) Abbasaliyev I.S., The Role of Transport Corridors in International Cooperation (Based on the Example of the Caspian Region) // Bulletin of the Northern (Arctic) Federal University. Series: Humanities and Social Sciences. Moscow, 2022. Vol. 22. No. 3.

(8) Brzezinski Z.,The Grand Chessboard. Moscow: International Relations, 1998. P. 26.

(9) See: Ilya Lakshtagal, Anton Kozlov, “What the First Decline in China’s Shipments Abroad Since 2016 Means”. Vedomosti (in Rus.), (13.01.2024), https://www.vedomosti.ru/economics/articles/2024/01/13/1014 874-chto-znachit-pervii-spad (download date: 07.05.2024); Trade volume between the European Union and China fell in 2024. TASS (in Rus.) // https://www.tass.ru/2025/01/13 (download date: 25.04.2025).

(10) See: https://t.me/bagramyan26/76526 (download date: 24.04.2025).

(11) See: China–U.S. trade turnover fell by 12.2% in 2023. RIA.ru (in Rus.), https://ria.ru.2023.12.07.html (download date: 02.04.2024).

(12) Scholz called for an investigation into the explosions at Nord Stream. RBC (in Rus.), 09/15/2024, https://www.rbc.ru/politics/15/09/2024/66e5f1479a794763b3da5e54ysclid=ma5fxs6jtq4495295 (download date: 28.04.2025).

(13) See: Artem Leonov, “Instead of Suez: from the Caspian to the Indian Ocean”. (in Rus.), https://www.stoletie.ru/rossiya_i_mir/vmesto_sueca_iz_kaspija_v_indijskij_okean_180.htm (download date: 24.09.2024).

(14) Ibid.

(15) Ibid.

(16) https://t/me/minval_az/95572 (download date: 27.09.2024).