Publication

On the Russian Federation’s geopolitical combination on the Georgian-Abkhazian track

ARVAK Center comment, 18.12.2024(1)

On December 14, 2024, presidential elections were held in Georgia under the new Constitutional law. According to the results of the Electoral collegium, consisting of members of the parliament and representatives of the regions of the republic, the nominee from the “Georgian Dream–Democratic Georgia” ruling party, a former player of “Alania” Russian football club and ex-deputy Mikhail Kavelashvili, was elected as the nominal head of state.

Thus, the second stage of the self-reproduction of the ruling force was completed, which, after the parliament, was able to secure the president’s post. May be the significance of this event for the “Georgian Dream” is not of a great importance from a practical standpoint, as according to the Constitution of Georgia, the president is endowed with purely representative functions and powers. However, in moral terms, the ruling party gained a great advantage, symbolically consolidating its victory under unprecedented Western pressure. It is obvious that the two-week surge of the opposition protest movement in Georgia was also connected with plans to boycott this vote, and the main role in managing these processes was played by the still-incumbent president Mrs. Salome Zourabichvili. The street actions did not lead to any tangible results, Zourabichvili’s team failed to disrupt the vote, and now she has no opportunity to prevent Mikhail Kavelashvili from taking office. S. Zourabichvili has already called the presidential elections a “parody”, but it seems that her main allies in the West do not fully agree with her.

On December 13, 2024, the day before the presidential elections, French president E. Macron addressed the Georgian people, calling on the authorities and the opposition to “establish dialogue and find a way out of the current deadlock together”. The French leader again reminded that the aspiration to become part of the EU is enshrined in the Georgian Constitution. At the same time, he noted that “Europe does not intimidate, does not use threats, Europe does not try to sow chaos, Europe does not try to destabilize neighbors or subjugate them by war or hybrid means”.

In fact, Macron acknowledged that the pressure exerted on the “Georgian Dream” has not yielded results so far, and his call for dialogue between the parties is due to the need to preserve the remnants of Western influence on Georgia. Otherwise, the continuation of the pressure policy will finally push the official Tbilisi away from Europe, increasing the “drift” of this South Caucasian republic towards the Russian Federation and the integration processes within the BRICS. Paris, thus, is trying to avoid a situation where the ruling force in Georgia may take radical steps and, for example, revise the Constitutional clause on the so-called “European path”, as well as change its decision on the moratorium on negotiations on joining the EU.

On November 28, 2024, the Georgian government announced that it was postponing this agenda until the end of 2028, but if the West continues to directly support the opposition’s street actions, Tbilisi may indefinitely annul any possibility of these negotiations. In turn, the West will no longer have effective levers to prevent such developments. The fact that Paris decided to backtrack and stop the process of the final degradation of Georgian-European relations is also evidenced by the telephone conversation held on December 11, 2024, between E. Macron and the Founder and Honorary Chairman of the “Georgian Dream” ruling party Bidzina Ivanishvili, during which the head of France, according to international media, offered his mediation to resolve the crisis.

It is noteworthy that France decided to “back-pedal” against the backdrop of the “tough measures” undertaken by the USA, which on December 13, 2024, announced the imposition of sanctions against 20 Georgian politicians and security officials who are “responsible for undermining democracy in Georgia”. Nevertheless, the actions of the USA and France may not indicate contradictions between them but rather coordinated efforts within the framework of a common goal to engage the Georgian authorities in contact and cooperation. It is clear that the imposition of personal sanctions against 20 individuals is by no means a strong blow to the political positions of the ruling force in Georgia, but it is a way to maintain Western influence on the Georgian opposition, prevent its potential from “dissipating”, and avoid despair in the protest segments of the Georgian society. Summarizing the new trends in the Western policy towards Georgia, it can be assumed that they believe that at this stage it is necessary to leave the Georgian authorities in relative peace, but at the same time continue to prepare for possible geopolitical shifts in the region as a whole, which may occur after the official inauguration of D. Trump, and which will also affect the Georgian agenda.

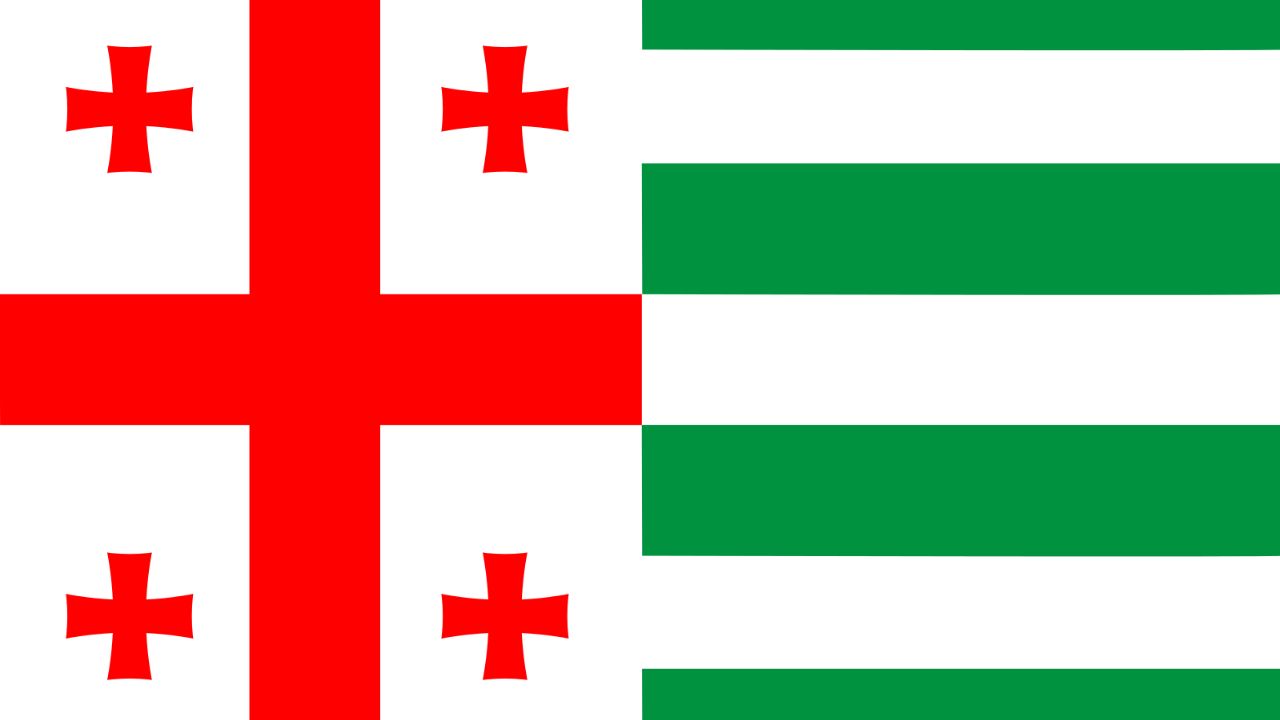

Meanwhile, the events in neighboring Abkhazia, which official Tbilisi continues to consider its integral part, are developing no less interestingly. The ARVAK Analytical Center has repeatedly written that the crisis situations in both republics are organically interconnected and the processes taking place there cannot be considered in isolation from each other. In Abkhazia, where opposition protests against the controversial law on expanding of the Russian investments began simultaneously with the recent protest actions in Georgia, the stage of dismantling the state system has essentially already begun.

After the resignation of president Aslan Bzhania and the withdrawal of the aforementioned controversial law, Moscow, according to the Russian media, began “disciplinary measures” against Sukhumi. Annual Russian subsidies intended to cover social costs and budgetary expenses of the small republic have been practically frozen; rolling blackouts have begun throughout Abkhazia; the export of Abkhaz agricultural products (mainly – citrus fruits) to Russia has been hindered; the Russian government has also banned domestic tour operators from organizing tours to Abkhazia.

The already fragile economy of the republic is in danger of collapse and causing a social explosion after such sanction measures. According to Russian media estimates, the “disciplinary measures” taken by Moscow are intended to “bring the Abkhaz people to their senses” and finally discourage them from resisting Russian private investments in the tourism sector and the state land fund of the republic.

The confidence of some Russian analytical circles in the effectiveness of such actions is debatable. There are no guarantees that the mentioned “measures” will lead to the submission of Abkhazian society, rather than to the growth of Russophobic sentiments in it. Such developments would have been impossible to imagine over the past three decades, but now the likelihood of such outcomes is extremely high. Short-sighted methods of coercion to loyalty through blackmail and punishment have long been compromised themselves in the Russian Federation foreign policy doctrine, examples of which can be seen in Ukraine, Moldova, Armenia, and Georgia in the 1990s and 2000s. In this case, the socio-economic “punishment” of Sukhumi may lead not to a social, but rather to a nationalist explosion, which certain forces in Abkhazia will not fail to take advantage of. And there are such forces there.

Despite all the difficulties associated with Russia’s substantial presence in this small republic, these forces have nevertheless been indirectly supported by external centers interested in anti-Russian sentiments among the Abkhaz people and the local clans that govern them. If the aforementioned Russian policy continues, it can be expected that these circles will not miss the opportunity to demonstrate a qualitatively different attitude towards the Abkhazian society against the backdrop of Moscow’s sanctions policy. For example, by organizing humanitarian convoys similar to the “Mavi Marmara” and providing humanitarian aid to the most vulnerable segments of the Abkhazian society.

The Abkhaz economy is indeed collapsing at an accelerated pace, society is extremely irritated, and it is difficult to imagine in what form Abkhazia will reach the extraordinary presidential elections scheduled for February 15, 2025. It already seems highly doubtful that the electorate will vote for a candidate who is loyal to Moscow and who is ready to return the “investment law” to the parliamentary agenda, which formally became the cause of the internal political crisis and the tension in the relations between Sukhumi and Moscow.

It is hardly worth considering that the Russian authorities do not understand the complexity of the issue. It is hardly conceivable that they do not realize that measures of social and economic pressure are destroying their most important political asset in Abkhazia — the loyalty of the Abkhaz people to the Russians and to Putin’s government in particular.

The ARVAK Center has written about the version that the Abkhaz crisis may have been initiated by Moscow, but not with the aim of obtaining rights to acquire land in the republic for construction, or to obtain additional benefits for Russian business, but for geopolitical tasks and levels. In particular, Moscow wanted to demonstrate to Georgian society the possibility of negotiating the reintegration of Abkhazia if the South Caucasian republic, following the parliamentary and presidential elections, abandons the Western vector. According to this logic, the crisis in Abkhazia, specially initiated by Moscow, can be considered as a support for B. Ivanishvili’s party, which included the following thesis in its pre-election campaign: abandoning the Western vector promises Georgia not only a guarantee of not “turning into” another Ukraine but also promises to increase the chances of reintegrating the once lost Abkhazia through warming relations with the Russian Federation.

This version seems to find new confirmations. The “Georgian Dream” has practically defeated the opposition, leaving the West no chance to bring ultra-liberals to power in Tbilisi by legal means at this time. Against this background, Moscow continues to destabilize the Abkhaz economy, clearly understanding that this measure will cause a surge of anti-Russian sentiments in Abkhazia. And here, it seems the most important nuance that sheds light on Moscow’s actions. This is about the characteristic handwriting of the Russian foreign policy team, which was also used in the case of Nagorno-Karabakh and even Syria.

For one reason or another, when making decisions about withdrawing from zones of military presence and geopolitical influence, Moscow traditionally refers to the loss of loyalty among its former allies and the growth of anti-Russian or openly Russophobic sentiments among them. If such sentiments do not actually exist, they are generated artificially. One should recall the Karabakh case, where by November 2020, Russia had almost 100% loyalty among the Armenian population, but within just three years, it completely lost this asset by deliberately not taking any actions to prevent Azerbaijani encroachments, illegal blockades, kidnappings of civilians, shelling, and other unconventional steps by Baku. At that time, Moscow’s priority was the issue of surrendering Nagorno-Karabakh within the framework of the foreign policy concept of “ensuring Azerbaijan’s loyalty.” Now a similar “deal” scheme is emerging with Tbilisi. In both cases, the victims of the “deal” are small republics and peoples who once had absolute trust in Russia but now are disappointed and practically abandoned by it, with accusations of ingratitude and Russophobia.

(1) The original (in Rus.) was posted on our website on 17.12.2024.