Publication

The “Final” disintegration of the Post-Soviet Space: building a new structure of regional relations

Expert’s comment, 21.08.2024(1)

Norayr A. Dunamalyan(2)

Over the past decade, the relevance of the term “post-Soviet space” has been questioned multiple times. Critics argue that the collapse of the USSR marked the fall of a colonial empire, where Russia’s dominance was the only unifying element. However, another perspective suggests that the Russian Federation, despite its continuity of the Soviet Union in the UN Security Council, became one of 19 republics (including de facto states) linked by a common social, political, and cultural heritage. Over time, the disintegration of this common humanitarian space and the transformation of post-Soviet societies led to a gradual distancing of the former Soviet republics from each other, contributing to regionalization. Until 2018-2020, relations between the countries of the former USSR were dominated by the “post-Soviet” logic of relations, which was replaced by a new quality of interaction due to the disruption of the balance of power within the Russian Federation’s influence zone.

The term “post-Soviet space” emerged during the unipolar “moment” of the 1990s and early 2000s, a period when a single superpower dominated the world. Following the collapse of the USSR, the United States sought to establish a system of hierarchical relations aimed at maintaining control over the geopolitical and geo-economic structures of various regions. Washington allowed certain powers to maintain a “free hand” in ensuring security and economic interaction, while simultaneously setting boundaries for the expansion of their geopolitical influence. The post-Soviet space was one such format, where Russian Federation (RF) dominance was accepted, provided it adhered to specific rules. These rules involved maintaining a balance of relations among the post-Soviet republics, positioning Russia not as a hegemon, but as an influential partner and mediator. Even after the five-day Georgian-Russian war in 2008, this system persisted, with conflicts between the RF and other republics (Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova, etc.) seen as efforts to delineate “red lines” within a unified relational framework.

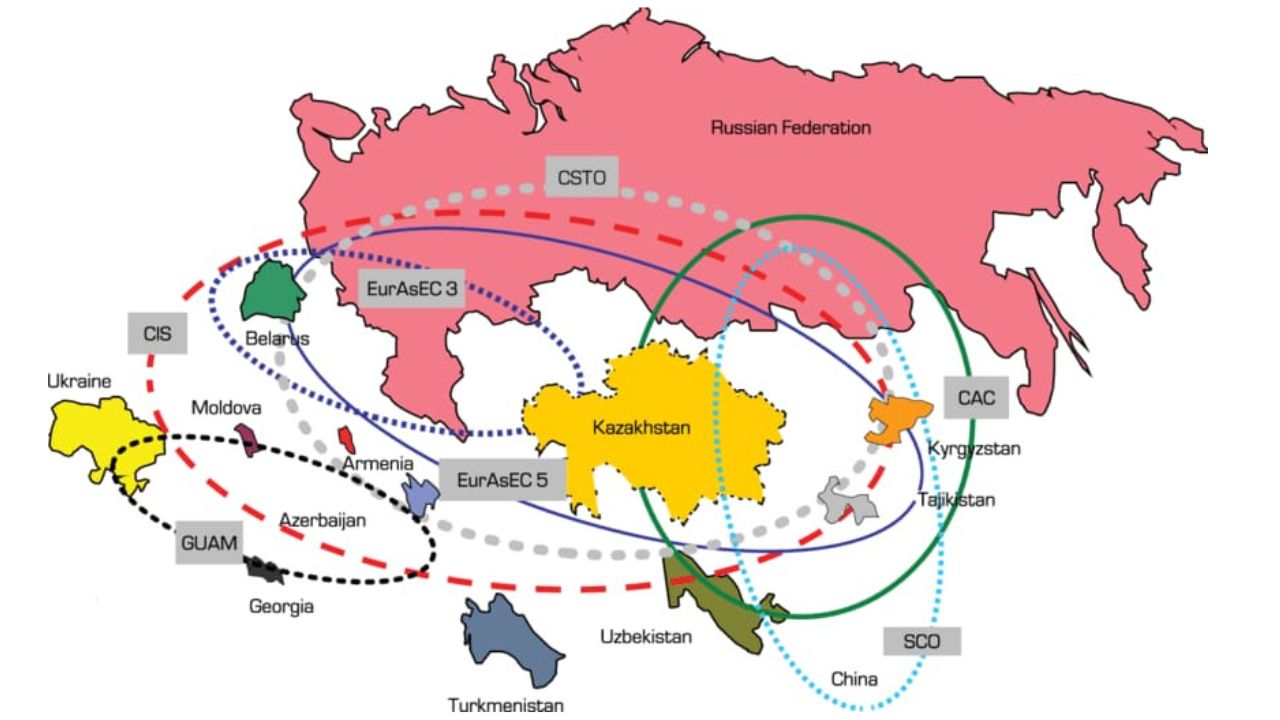

The transformation of these relations coincided with the growing independence of regional actors, who gradually sought to distance themselves from the RF. While the CIS and CSTO formats represented a “soft” integration of the post-Soviet space (considering the Baltic republics joined NATO and the EU), the creation of the EAEU was a response to the crisis in relations among the post-Soviet republics, reflecting Russia’s desire to maintain its influence. The main issue was that attempts to “preserve” the previous relational structure occurred against the backdrop of the disintegration of the global world order. Signs of international change were evident in the increasing influence of external players (notably the EU, Great Britain, China, and Turkey) in the so-called Near Abroad of the RF, as well as the diminishing role of the United States in global processes.

The structure of post-Soviet relations consisted of several components common to all participants in this space: the factor of personal relations between the heads of state; a stable system of local conflicts; the ideological role of Russia as the main “ally” or “antagonist”; and the desire to strengthen relations with the USA and the EU. All these elements were subsequently revised for both objective and subjective reasons, altering the essence of interactions between the countries of the former USSR. Over the last 30 years, the generation of “Soviet” politicians has been replaced in many republics, the policy of “brotherhood/enmity” has shifted to radical pragmatism, and foreign policy vectors have been reoriented towards the East and South. Additionally, the role of unrecognized states has been revised, transforming from a “lever of pressure” to a “bargaining object,” as the cases of Donbass or Karabakh can be projected onto the Transnistrian and Abkhaz-Ossetian situations, depending on the behavior of Moldova and Georgia, respectively.

In any case, the ethno-political conflicts of the post-Soviet space are beginning to bear the imprint of global confrontation. While a common humanitarian space, culture, Russian language, and political and economic ties could be considered components of post-Soviet relations, these are not key elements. Their replacement or recombination would not lead to significant destabilization, unlike the aforementioned circumstances.

Reflection of the collapsing world order on the post-Soviet space

The collapse of the post-Soviet space does not signify a decline in Russia’s influence but rather a significant revision of its foreign policy. The “rules-based international order” proposed by the West has been met with little enthusiasm from Russia and China, who accuse the U.S. and its allies of hypocrisy and “double standards.” In response, the strategic competitors of the United States advocate for building international relations based on “mutually beneficial cooperation,” which entails rejecting any ideological pressure on states in exchange for political rapprochement. Thus, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Russia propose a more inclusive model of interaction that does not imply ideological influence. The main condition is non-interference in domestic politics and a refusal to support the West. This formula, while contradictory, is attractive to developing countries where personal power regimes are not ready to adhere to any rules, at least in domestic politics.

Overcoming the “post-Soviet” logic of interaction, the space of the former USSR is moving towards a process of hierarchical relations based on the role and influence of certain states in Eastern Europe, the South Caucasus, or Central Asia. In this context, “mutually beneficial cooperation” does not imply status equality, as the category of regional leadership is highlighted. States may not claim global roles but can play important roles in the “links” of subordination. In the event of a final reduction in the U.S. role on the global stage, several such “chains of subordination” may arise around the RF and PRC, in Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, etc. This format of interaction is already being constructed today and represents an attempt to prepare for a possible global mega-crisis.

Ironically, the regional configuration in the post-Soviet space was created thanks to the Russian trend of Orientalism in the first half of the 19th century, when concepts such as “Malorossia” (“Little Russia”), “Transcaucasia,” and “Central Asia” came into use. Under the Provisional Government and the Bolsheviks, these territorial phenomena received institutionalization and borders, as well as a high level of independence. In the post-Soviet period, the independence of the former outskirts of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union prompted Russian elites to consider the destruction of old geopolitical models, emphasizing the security and development of the RF territory alone.

Such an approach provoked a rollback to the conditionally “pre-Russian” regional configuration (the borders of the 18th century), which was strengthened by the fragmentation of the post-Soviet space over the past 30 years. The return to the “pre-Russian” situation in various regions of the post-Soviet space implies a de facto “division” of zones of influence between Russia and other actors. For instance, in the case of Belarus, Ukraine, or Moldova, this division involves Eastern European countries; in the South Caucasus, it involves Turkey, Iran, or China; and in Central Asia, it involves China and Iran (specifically in the case of Tajikistan). By “division,” it is meant coordinated actions regarding the resources, potential, and strategic importance of a specific region for Russia and other powers, with the aim of expelling the “political West”.

That is why interest in BRICS+ and the SCO has grown significantly since February 2022. Russia has leveraged its “assets” in the form of influence over the post-Soviet republics to attract new “investors” for the implementation of common tasks. Consequently, some events should not be perceived as coincidences: the inclusion of Belarus in the SCO; the active participation of Azerbaijan in the SCO meeting, the signing of an agreement with China, and provocations against France; the conflict between Georgia and the West against the backdrop of launching the construction of a port in Anaklia by a Chinese company, etc. In this context, each state (or rather, the ruling class) of the post-post-Soviet space is trying to secure the most advantageous position for itself.

This position is also influenced by the ambitions of the states bordering the post-Soviet space, which are interested in the continued fragmentation of Russia’s sphere of influence. The EU’s “European Neighborhood” program has become a major trigger for reconsidering regional relations within the post-Soviet space. The conflict over Ukraine and the Russian-Armenian crisis of 2013 were the result of rapprochement with the EU within the framework of the “Eastern Partnership.” Following the outbreak of hostilities in Ukraine, the South Caucasus and Central Asia have become strategically important regions for the European Union in terms of security and transport routes, as well as diversification of energy and resource supplies.

At the sub-regional level, one can note the longtime Polish project “Intermarium” (positioned today through the project “Three Seas Initiative”), aiming to involve the Baltics, Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova in its orbit, which is facilitated by Russia’s “military operation” in Ukraine. The Belarusian authorities are using this circumstance to mobilize the population in the face of a “common threat with Russia.” At the same time, the process of delegitimization of A. Lukashenko’s power in 2020 led to complete loyalty to Moscow and the search for ways to include Minsk in new formats of cooperation in the East (within the framework of the SCO, BRICS, or cooperation with Cuba, Venezuela, Azerbaijan, etc.). In fact, Belarus has today become an “avatar” of Russia, representing the main directions of Russian geopolitics in a concentrated form.

There is a widespread opinion that the U.S. is acting through Poland’s “hands”, but despite all the support from Washington, one circumstance should be noted: Warsaw, lacking extensive military-political or economic capabilities, has long used the EU’s potential to assert its nationalist claims. It is noteworthy that the “post-Communist” countries of Eastern Europe (Poland, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia and others) are still seeking for their national identity, and active “expansionist” policies remain on the agenda. The same situation leads to Turkey’s increased activity in the South Caucasus and Central Asia.

Even though some critical tensions can be seen in Turkey’s positions today, which are influenced, first of all, by the loss of ground in the domestic political sphere, R. Erdogan, in 2020, with his support for Azerbaijan, initiated the mechanism of the final disintegration of the post-Soviet space. It is not about the loss of Nagorno-Karabakh, which became a start of Russia’s expulsion from the region, but about a complete revision of the rules of regional interaction that have been established over 30 years. In fact, Turkey “intervened” in the post-Soviet space and defeated one of the states of this region without meeting any resistance from the countries of this space; on the contrary, many welcomed Armenia’s defeat. In addition, the “Organization of Turkic States” was created as an alternative format to the CIS, which strengthened the rivalry between Turkey and Russia in the post-Soviet space. This resulted in a violation of the regional order, which was reflected in the war in Ukraine.

However, the most important actor in the revision of regional relations remains the PRC, whose infrastructure projects lead to the integration of post-Soviet countries into more global interaction formats. The transit through Central Asia and the South Caucasus promises great benefits to the post-Soviet states, but at the same time ties them up to the investor countries.

The cost of cooperation with “regional leaders”:The Predictability Factor

The presence of “non-traditional” actors in the post-Soviet space is compelling the Russian Federation to develop new formats of relations. These formats, in many respects, resemble American ones and reflect a desire to cooperate with so-called “regional leaders” who, in turn, can establish a more predictable system of political and economic ties around themselves. The predictability factor is crucial regarding these countries’ reactions to Russia’s foreign policy moves and their relative independence from Western influence. Notably, such “independence” from the West can be demonstrated rhetorically, which suits the Russian leadership quite well.

Since 2022, Russia’s intention to secure its geopolitical position has led to deepening relations with several “regional leaders” in the South Caucasus and Central Asia. The signing of the Declaration on Allied Interaction between the Russian Federation and Azerbaijan aimed to consolidate the “successes” of Russian diplomacy in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict zone and present new priorities for cooperation in this region. With this step, Russia contributed to the dismantling of the post-Soviet balance of power in the South Caucasus, appointing Azerbaijan as a “regional leader” (a status later confirmed by A. Lukashenko). Azerbaijan had already considered itself the leader of the South Caucasus region, but today such claims have become institutionalized. Paradoxically, the relations being built against the backdrop of the collapsing world order are conjunctural (Russia is trying to find new transport routes for the transportation of goods and hydrocarbons to world markets), which is reflected in the drastic changes in the rhetoric of Russian officials. However, new formats of relations are being built without a clear prospect for their development (the main prospect being the destruction of the old World Order). In Central Asia, Uzbekistan’s role, with the highest GDP growth rates in the region and the greatest demographic potential, is gradually increasing. Simultaneously, there is a rapprochement between Russia and the regime of S. Japarov, who came to power in Kyrgyzstan in 2020. Along with authoritarian tendencies, he has shown a rather loyal attitude towards the SMO in Ukraine. Thus, Russia prefers “predictable” regimes with which it is possible to conduct a direct dialogue through stable political relations. This is largely facilitated by the similarity of political regimes.

Among the “unpredictable” regimes today, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Moldova, and Georgia stand out, as the political elites of these states are committed to considering several alternatives in their foreign policy to diversify geopolitical and economic risks. In this context, Kazakhstan, the most economically developed state in Central Asia, is particularly interesting. It has long claimed a high degree of independence, leading to periodic conflicts with the Russian Federation. Additionally, the EU remains Kazakhstan’s main economic partner, and diversifying the transportation of goods and energy resources (with the main Kazakh oil pipeline passing through Russian territory) remains a top priority for the republic. The forming “Moscow-Tashkent-Bishkek” axis within the framework of transport and economic cooperation is a response to Astana’s actions. In turn, cooperation with China is crucial for Kazakhstan as a possible alternative, although its close cooperation with the same regional competitors of Astana leads to the search for deeper ties with the EU, Great Britain, and Turkey. Furthermore, Kazakhstan proposes creating a regional defense union, which could reduce the influence of Russia and China in the long term.

The hybrid regimes of Armenia, Moldova, and Georgia are the most vulnerable, as their geopolitical orientation may be unstable under current conditions. In Moldova, rapprochement with Romania continues, but issues with Gagauzia and Transnistria persist, contributing to the geopolitical fragmentation of the republic. Georgian political elites take an extremely pragmatic stance regarding relations with Russia, China, and the West, but the upcoming elections in October may destabilize the country’s political system. As the weakest link among the post-Soviet republics, Armenia is trying to balance the interests of various global and regional actors, which, in the context of global confrontation, turns the territory of the republic into a “field of geopolitical experiments.”

It is noteworthy that Tajikistan, sharing a border with the newly established Emirate of Afghanistan, is excluded from many infrastructure projects due to the insularity of its railway line and challenging terrain. To involve the republic in North-South or West-East projects, a developed transportation system linking Central and South Asia is necessary. However, the situation in Afghanistan and competition between China and India hinder this development. Tajikistan largely remains within the old coordinate system, although in recent years, the country’s leadership has established close cooperation with Iran.

Several critical problems arise from this situation. First, in the context of confrontation with the West over Ukraine, Russia is attempting to build an intermediate regional order based on “predictability.” This approach highlights certain “regional leaders” while creating mechanisms to restrain the “geopolitical turnaround” of hesitant regimes. Secondly, an important factor that complicates the future picture of relations in the “post-post-Soviet” space is Ukraine’s fate after the end of military actions. The position of Ukraine post-war will be crucial in shaping the balance of power in Eastern Europe, although it is clear that this conflict is not the key to changing the world order (similar to the Soviet-Finnish war of 1939-1940).

Focusing on tactical steps increases future threats. The current actions of post-Soviet elites are based on existing crisis situations, with each state trying to navigate the global collapse in the best-prepared form. Consequently, military expenditures are rising, new military-political alliances are forming, economic and migration legislation is becoming stricter, and the need for social consolidation is growing. Since these are predominantly authoritarian regimes, this leads to increased levels of foreign and domestic political aggression, which, from a strategic perspective, can result in regional chaos.

“Anti-Russias” versus “Anti-America”

When discussing the contradictory nature of the non-Western alternative to the world order, it is important to remember that the U.S., while promoting its vision of hierarchical regional relations, has always had an additional strategy. This strategy involves creating numerous connections and counterbalances at the regional level to prevent the emergence of a single hegemonic power. This approach can be termed “controlled multipolarity.” Zbigniew Brzezinski highlighted the crucial roles of Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, and Ukraine in containing Russian “imperial” ambitions. Today, we see a significant increase in the importance of these countries for Russian foreign policy.

In other words, by contributing to the dismantling of previous relations, Russia is providing tactical support to regimes that have historically pursued a balanced policy toward various centers of power. Simultaneously, the foreign policy approaches of these states are being adopted by countries that were previously loyal to Moscow. The situation is further complicated by the ongoing military actions in Ukraine, which, once concluded, may significantly transform the geopolitical landscape around Russia. This transformation could lead to the emergence of new “anti-Russias” seeking to distance themselves from Russian influence.

The problem, in many respects, is that Russia itself has “turned” the geopolitical game, using the theme of the USSR’s revival or justifying its actions with “Leninist” projects of confederation, which merely serve as rhetoric masking the dissolution of the post-Soviet space in a broader global context. Even the term “special military operation” was intended to indicate a certain limitation and precision of Russian actions in Ukraine, but two years of war have altered the entire picture. The Russian leadership’s attempt to portray the war in Ukraine as analogous to American operations in Iraq or Afghanistan demonstrated the Russian elite’s desire to emphasize similarities with U.S. foreign policy. Russia’s pursuit of “controlled multipolarity” in the post-Soviet space also reveals its lack of a coherent strategy for building stable relations with neighboring countries. In fact, two negative agendas have collided in the post-Soviet space: anti-Russian and anti-American, contributing to the gradual disintegration of this macro-region.

Birth of the “Eurasian Balkans” (instead of Conclusion)

The regions of the South Caucasus and Central Asia are becoming a unified space thanks to various trade and infrastructure initiatives. The transit of goods between Europe and China has become a key focus of transportation projects in many post-Soviet republics. This has created a demand for closer ties between South Caucasian and Central Asian countries. Azerbaijan, due to its cultural and political-geographical characteristics, has long been perceived as part of Central Asia rather than the South Caucasus. All multimodal transportation routes from Central Asia (e.g., the Middle Corridor) necessarily include Baku as a key transportation hub for moving goods through Georgia to Europe. Additionally, discussions about the so-called “Zangezur Corridor” are also part of the formation of new regional relations. However, there are many questions about the positions of Russia and Iran, but the process of creating the “Eurasian Balkans” (as Zbigniew Brzezinski termed it) has already begun.

Thus, the geopolitical “Great Game” in the post-Soviet space is just beginning, involving not only the West and Russia but also other actors, particularly China. The conflict in the Middle East can also be seen in the context of Iran’s “opening” to new global initiatives, which promote both U.S. and Chinese interests in developing Eurasian transport routes. In this context, many players are trying to neutralize Russia, which cannot afford to take active actions even in its near abroad due to the war in Ukraine. Consequently, by the end of the military actions in Eastern Europe, the entire “southern zone” of the former post-Soviet space may be transformed beyond recognition.

(1) The original (in Rus.) was posted on our website on 16.08.2024.

(2) Candidate of Political Sciences, Associate Professor of the Department of Political Science at the Russian-Armenian (Slavic) University. Author of more than 20 scientific papers and articles.